紀念Howard Hodgkin 漢清講堂 2017-03-18

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3iV0DSTw584

Howard Hodgkin: Paintings That Shout

http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/04/09/howard-hodgkin-absent-friends-paintings-that-shout/

“Absent Friends,” the title of the current exhibition of Howard Hodgkin’s portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, is doubly poignant: Hodgkin died on March 9, two weeks before it opened. He had been thrilled that a show would focus on his portraits, always an important strand in his work: “At last! At last!” he said when he was told of the NPG’s plans. The exhibition’s curator, Paul Moorhouse, heard the news of Hodgkin’s death a half hour before his team was due to start hanging the paintings.

It always feels wrong to scatter words around Howard Hodgkin’s paintings. Their tactile richness should just burn into eyes and minds, leaving a trace behind the eyelids, a memory to which we can return. Their energy is enormous, their beauty intense. Yet “words” are eerily present in these paintings: conversations, jokes, arguments, and endearments. In a way, Hodgkin is a narrative artist and it’s not surprising that he numbered writers among his close friends: Bruce Chatwin, Colm Tóibín, James Fenton, Julian Barnes. All these have written eloquently about him. But he didn’t, himself, like talking about his art, and hapless interviewers often met heavy silences, monosyllabic replies, or airy dismissals. And now he is gone, and there is no one to ask, just the paintings to speak for themselves. And speak they do. Their voices collide, tumble, whisper, sing, shout.

Inevitably, the portraits make one curious about the artist’s life as well as his work. When a famous person dies we learn facts. So: Howard Hodgkin was born in 1932 into a well-off family with smart, intellectual, Bloomsbury connections—his father was a manager at ICI (Imperial Chemicals) and a collector of rare plants, his mother the daughter of a Lord Chief Justice, and Roger Fry was his cousin. He wanted to paint from the age of six: saying that he was off to be an artist, he ran away from different schools, including Eton, where the art teacher, Wilfred Blunt, introduced him to the glory of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Indian miniatures, of which he later became a renowned collector.

Then came the war, when Howard and his mother were evacuated to Long Island—Fitzgerald country, as he remembered it—and on his return he studied at Camberwell and the Bath Academy of Art in Wiltshire. Hodgkin belonged to the generation that came to the fore in the late Fifties and Sixties, including Patrick Caulfield, Peter Blake, and David Hockney. Caulfield is present here in the briskly linear Mr and Mrs Patrick Caulfield (1967-1970) and the later, luscious Patrick in Italy (1991-1993), and Hockney in the affectionately witty DH in Hollywood, (1980-1984), where blue dots hint at a swimming pool and generous palm-frond swirls flank a pink phallic column.

Although Hodgkin’s canvases were striking, he gained fame slowly, suffering from the mid-twentieth-century disdain for figurative painting. True recognition came only in the mid-1970s, heightened after 1984 when he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. He worked slowly too—“tortoise-like,” he admitted. An idea could stay in his mind for years before it was bodied forth.

In “Words for H.H.,” written in 2001, Julian Barnes recalled him sitting in a bar or restaurant when they were travelling, saying, “with a delivery poised between self-satire and true contentment, ‘I feel a picture coming on.’” This reminded me of Seamus Heaney’s description of a poem “coming on,” swimming upwards from somewhere deeper than the reach of words, raiding the inarticulate. Hodgkin’s work is almost always about memory, but, as Barnes also says, “this was not a case of emotion recollected in tranquillity. Rather it is emotion recollected in intensity. In that sense, his pictures are operatic.” The theatrical feeling of curtains opening on deeply-felt moments is intensified by Hodgkin’s frames, splodged and streaked so that they both become part of the vision and enclose it. “The more evanescent the emotion I want to convey,” he once said, “the thicker the panel, the heavier the framing, the more elaborate the border, so that this delicate thing will remain protected and intact.”

The current exhibition—retrospective in more ways than one—is all about the staging of recall. It begins with a small painting done when Hodgkin was seventeen, Memoirs (1949), in which a seated figure is listening to a woman stretched out on a couch. The speaker was Aunt Bette, a family friend from Long Island, but despite surrounding her with stark details of photos, plants, and a glittering ring, Hodgkin chose not to show her head, a foretaste of the way so much would be hidden as well as revealed in his work.

This is a joyous show. After the angular vividness of the early drawings—people he knew well, already drawn from memory—you turn a corner into a light-filled room, and immediately the realism gives way to swirls and dots, lines and curves, employed to conjure couples and friends and intimate gatherings. There are touches of homage to the painters he admired, to the gestural poses of Degas, to the seductive light of Bonnard and the decorative, voyeuristic intimacy of Vuillard, but the vision and execution is distinctively his own.

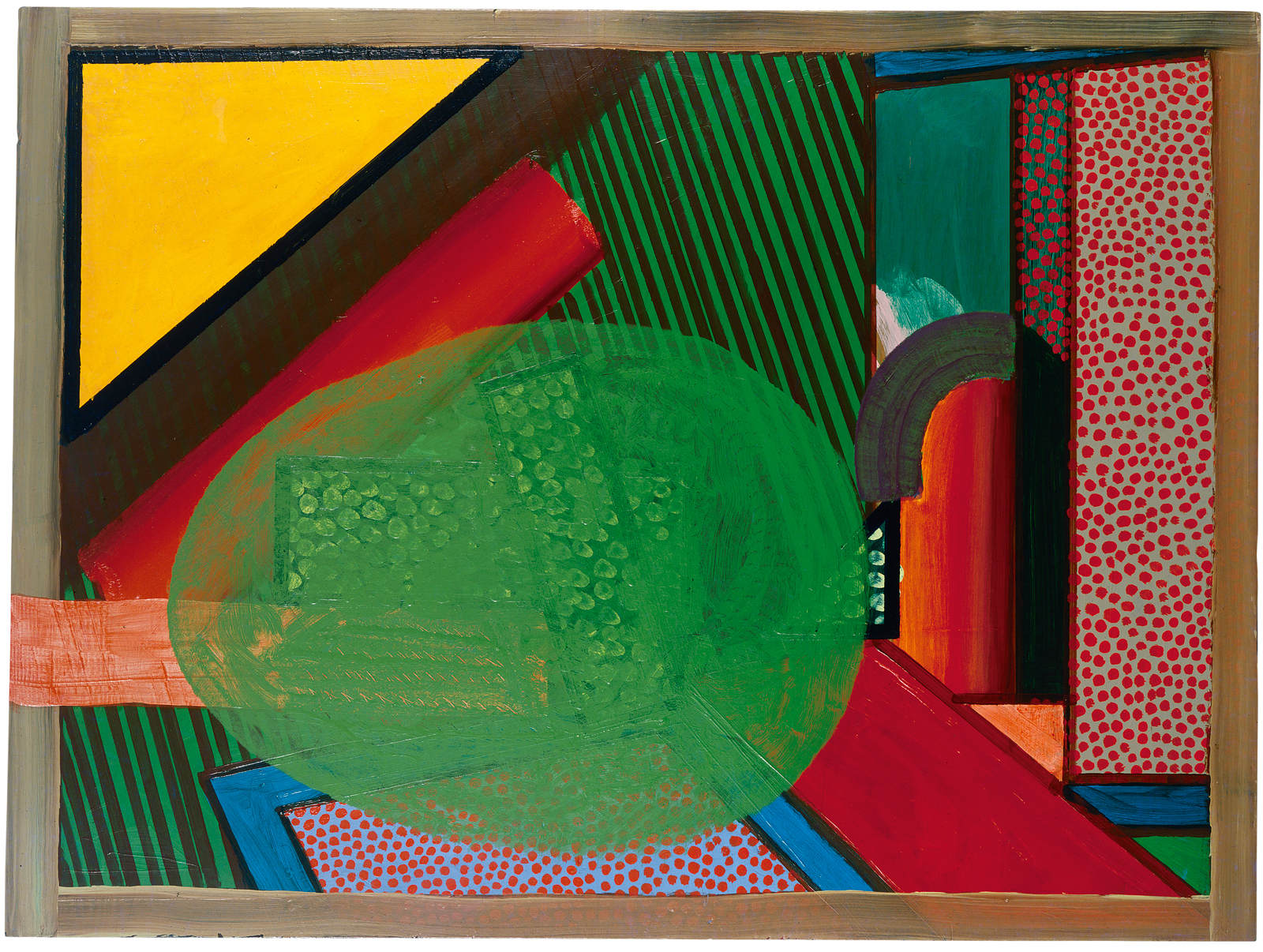

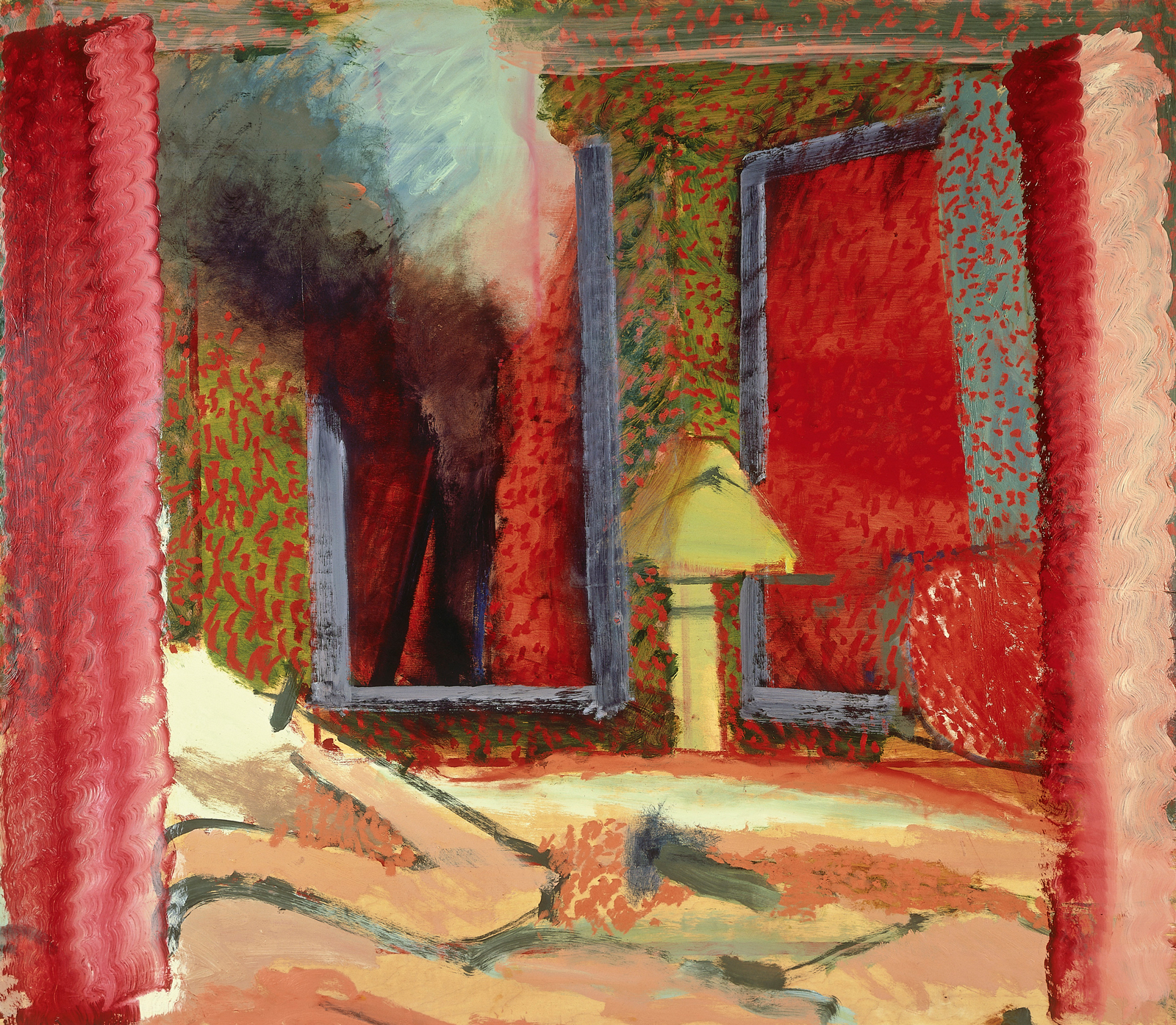

The figurative swerves into the abstract, a complex language of encounters, or in Hodgkin’s words, “emotional situations.” Titles often tease: Talking about Art (1975), for example, recalls conversations with the artist Peter Kinley, where “the art world” was stoutly avoided. And the pictures tease too, with in-jokes, like the enveloping talk of the collector Ted Powers, a huge green egg swelling across the firm lines of Mr and Mrs E.J.P. (1969-1973). One painting from this time that I could return to again and again is simply called Interior with Figures (1977-1984). It shows a room like a stage set, in shades of rose and plum and grey, with a single yellow lamp. The foreground holds a recumbent, cigarette-smoking form, and behind him a misty shape arises like a genie from a bottle. It took him seven years to paint.

In the work of the mid-1980s all hesitancy disappears: in Waking up in Naples (1980-1984) and In Bed in Venice (1984-1988), the cherished moments are exuberantly erotic. In this decade Hodgkin parted from his wife, Julia Lane, with whom he had two sons, and began a lifelong partnership with the musicologist Anthony Peattie. After 1980 he said he felt “able to put more of myself” into his paintings. In the portraits he is there as a shadow or a line. In Self-Portrait (1983) he peers through thumb-prints of Charles of the Ritz make-up, but in the vivid The Spectator (1984-1987) and Portrait of the Artist (1984-1987), or the glowing prism of A Small Thing but My Own (1983-1985) he is present simply in the intensity of the marks themselves.

Hodgkin spent much of his last year in India, where he had gone annually since the 1950s, travelling, collecting, painting. In his Mumbai studio, heaving himself up out of his wheelchair, he worked on six large paintings for another show, Painting India, which will open in June at the Hepworth Wakefield. At the National Portrait Gallery, the grand finale is a similar performance of supreme effort, painted especially for the show: Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music, (2011-2016). As he worked, Jerome Kern’s The Last Time I Saw Paris, and the zither music from the 1949 film The Third Man, played on a loop.

Held up by his assistant, he used long, specially-made brushes and the resulting huge, arching strokes seem to make him physically a part of his work, braving time and age. Yet any monumentality is offset by three small paintings hung nearby, gestures to women friends—Kathy Sachs in Kathy at La Heuzé (Flame against Flint) from 1997-1998, a swirl of gold flame against grey; Blue Portrait (2011-2012) a double curve of two shades of blue, remembering Selina Fellowes glimpsed at a theater bar in a brilliant blue dress; and Tears for Nan (2014), painted after the death of the curator Nan Rosenthal, drops of yellow and green, a spring-burst against darkness.

The labels for the exhibition were put up before Hodgkin died. It tugged at my heart to read that “now eighty-four years old, the artist continues to paint.” But while these pictures remain so vibrantly, splendidly present, I think he does.

“Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends” is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, through June 18. The catalog by the same name, by the exhibition’s curator Paul Moorhouse, is published by the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Material Type:圖書

Howard Hodgkin the complete paintings : catalogue raisonné

Price, Marla. Hodgkin, Howard, 1932- ; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

New York : Thames & Hudson ; Fort Worth, Tex. : In Association with the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas 2006

Material Type:圖書

Howard Hodgkin : the complete prints

Heenk, Liesbeth.

London : Thames & Hudson c2003

Howard Hodgkin by Andrew Graham-Dixon

Thames and Hudson, 192 pp, £24.95, October 1994

Material Type:

Howard Hodgkin

Graham-Dixon, Andrew.

New York, NY : Thames & Hudson c2001

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A catalogue raisonné is a comprehensive, annotated listing of all the known artworks by an artist either in a particular medium or all media.[2] The works are described in such a way that they may be reliably identified by third parties.

There are many variations, both broader and narrower than "all the works" or "one artist". The parameters may be restricted to one type of art work by one artist or widened to all the works by a group of artists.

It can take many years to complete a catalogue raisonné and large teams of researchers are sometimes employed on the task. For example, it was reported in 2013 that the Dedalus Foundation (established by the abstract-expressionist painter Robert Motherwell) took 11 years to complete the three-volume catalogue raisonné of Motherwell’s work which was published by Yale University Press in 2012,[3]with approximately 25 people contributing to the project.[4]

Early examples consisted of two distinct parts, a biography and the catalogue itself. Their modern counterpart is the critical catalogue which may contain personal views of the author.[5]

Contents

[hide]Grammatical and linguistic matters[edit]

The term catalogue raisonné is French, meaning "reasoned catalogue"[6] (i.e., containing arguments for the information given, such as attributions.) but is part of the technical terminology of the English-speaking art world. The spelling is never Americanized to "catalog", even in the United States.[7][8] The French pluralization "catalogues raisonnés" is used.[9][10]

沒有留言:

張貼留言