The Paris Review

In 1924, Otto Dix produced “Der Krieg” (The War), a cycle of fifty-one demented and harrowing prints that document his experience in WWI.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

In 1924, Otto Dix produced “Der Krieg” (The War), a cycle of fifty-one demented and harrowing prints that document his experience in WWI.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

For Throwback Thursday from our Library & Archives, view 1920s prints by German artist Otto Dix based on his memories of serving in World War I: http://gu.gg/LI2p1

Otto Dix

(born Dec. 2, 1891, Untermhaus, Thuringia, Ger. — died July 25, 1969, Singen, Baden-Württemberg, W.Ger.) German painter and printmaker. He studied at the academies of Düsseldorf and Dresden and experimented with Impressionism and Dada before arriving at Expressionism with a nightmarish personal vision of contemporary social reality, depicting the horrors of war and the depravities of a decadent society with great emotional effect. He was appointed professor at the Dresden Academy in 1926 and elected to the Prussian Academy in 1931. His antimilitary works aroused the wrath of the Nazi regime and he was dismissed from his academic posts in 1933. His later work was marked by religious mysticism. See also Neue Sachlichkeit.

How German was Otto Dix? The question echoes through the retrospective of Dix’s unforgiving art, the first show of its kind ever held in North America, at the Neue Galerie. The answer delivered by this completely engrossing yet sadly flawed exhibition is: deeply, madly, truly.

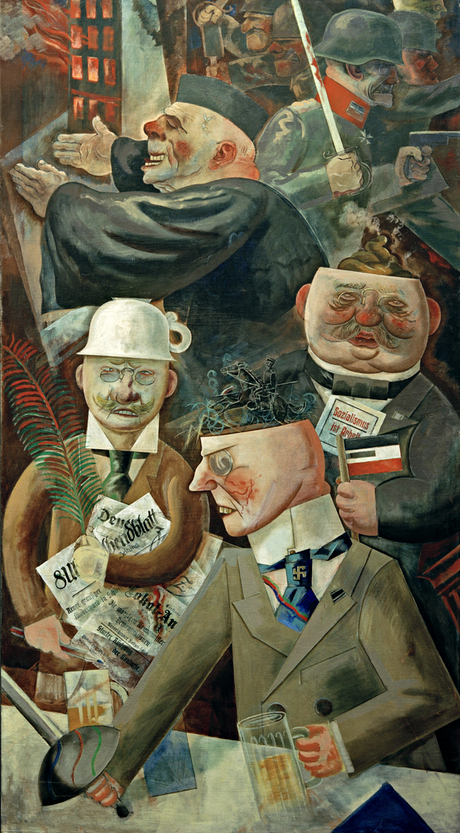

More than any other artist, Dix made every stop on the itinerary of German modernism, including Realism, Dada, Surrealism, Expressionism and visionary, and he managed it all in one decade, the Roaring ’20s. The critic Paul Ferdinand Schmidt — who appears here in a James Ensor-like group portrait from 1923 along with the art dealers Günther Franke and Karl Nierendorf — conjured this whirlwind tour in 1926, when he described how “Dix comes along like a natural disaster: outrageous, inexplicably devastating, like the explosion of a volcano. One never knows what to expect from this wild man.”

There are many sides to Dix, the son of an ironworker, whose talent for drawing was spotted early and led to study in an art academy in Dresden, with its great museums. In the 1920s he was invited to paint Hans Luther, a chancellor of the Weimar Republic. But he not only painted very different subjects, like prostitutes and crime scenes, he did so in ways that pushed his materials to the limit. His 1923 watercolor of a brothel matron verges on automatism. Elsewhere he borrowed from folk art, as with the quasi-naïve “Sunday Stroll” (1922) and its nuclear family; its members seem to swing from invisible strings like puppets.

As German painters often still do, Dix believed that the medium’s entire history — especially the German part — was available for his use. He painted in the small-brush smooth-surface manner of Albrecht Dürer and looked to Lucas Cranach for inspiration. With contemporaries like Christian Schad, he contributed to a perverse new style of realist painting, called the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) that emerged in 1925. By then he had already presented “The Skat Players,” a scathing 1920 Cubo-Expressionist collage-painting of postwar German amputees playing cards, at the landmark exhibition that the Dadaists staged in Berlin that year. That work is not here, but a small, bristling, tightly wound study conveys some of its vehemence; it is, unfortunately, one of the few pencil drawings included in this version of the show, organized with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where it will be somewhat larger.

Dix portrayed a multitude of Germanic types — from stoic farmers to limbs-akimbo Weimar demimondaines — as surely as the German photographer August Sander, often with the same penchant for capturing the Lutheran dignity of his subjects. But Dix, who was born in 1891, 15 years after Sander, and saw action in World War I, tended toward something less generous and more freakish. I doubt that Sander would have considered titling an image “Dedicated to Sadists,” as Dix did with a 1922 watercolor. He insinuated all manner of sly caricature, disgust and fury into many of his renderings. In addition to the horribly disfigured faces of war veterans, he also liked to depict, usually in watercolor and ink, the mutilated bodies of murdered women, victims of lustmord, or sexual murder.

There are numerous half-nude female models, signaling an unrepentant, usually unflattering fixation on female breasts; Dix often seems to have equated women with dumbness, whether brute or weak. But he could be intermittently sympathetic, especially concerning the downtrodden or the creative, as evidenced by early portraits like “Working-Class Boy,” which calls to mind Alice Neel’s paintings, and “Unemployed Man,” and by later ones of the poet Iwar von Lücken and the philosopher Max Scheler. A borderline case is the rarely exhibited “Two Children” from 1921, whose subjects seem innocent and open, despite strangely deformed features, and is more Diane Arbus than Neel.

Dix himself, who appears in several photographs early in the exhibition, three taken by his friend Hugo Erfurth and one by Sander himself, looked impeccably German — or Aryan as it would soon be called. A dandyish dresser, he was lean and fair-haired, with high cheek bones and narrow, penetrating eyes. Depending on how he cut and combed his hair, he resembled a Holbein portrait, an international (or Nazi) spy or an ascetic artist.

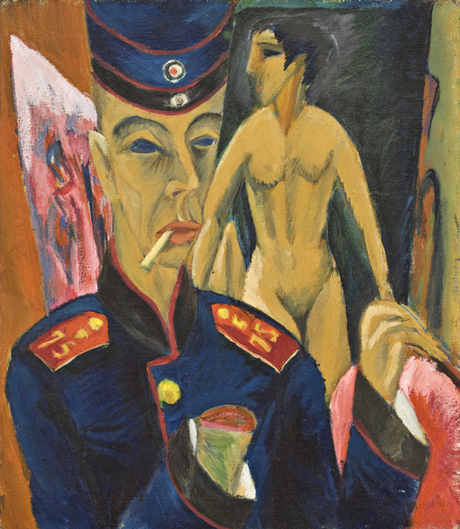

Dix’s self-portraits could flatter. “Self-Portrait with Nude Model” (1923) features a chiseled and smartly clothed Dix with slicked-back hair and at his side a curvy, slightly dopey-looking woman, her hair frazzled — although she has been awarded the luminous eyes of a seer. (So has “Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann” from 1920.) Yet he could also be as hard on himself as on anyone else. In a black-chalk drawing from 1917, he has long, sharp eye-teeth and a demonic vampire look. In “The Artist’s Family” (1927), painted a decade later, his wife, daughter and infant son fill the frame, while he seems to intrude from the right, like a handyman with bad teeth who usually keeps to the barn.

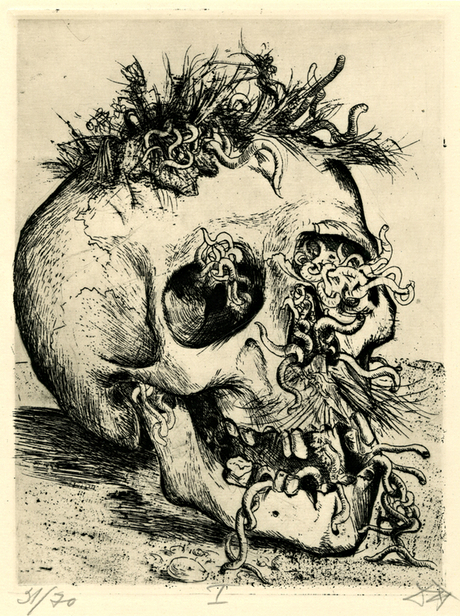

As with most German artists of his generation, Dix’s formative experience was World War I. He emerged from nearly four years in the trenches physically unscathed but psychically scarred. He attempted exorcism with “Der Krieg” (“The War”), a suite of 50 mostly masterly etchings published by Nierendorf in 1924. They convey a searing sense of the physical horror of war — most prominently wounded and rotting flesh — that remains unmatched in the history of art.

When the Nazis loomed, Dix closed one eye, made satiric references and also turned to images of mothers dandling or nursing infants, although painting women sincerely was hardly his forte. And when the Nazis came to power he was quickly dismissed from his teaching position at the Dresden academy. He was included in the famous 1937 degenerate art exhibition, and the Nazis ultimately impounded 260 of his works from German collections. Dix went into internal exile on Lake Constance. There he took to painting hyper-detailed landscapes that sometimes leaned toward Caspar David Friedrich, sometimes toward Breughel tinged with some of the weirdness of Max Klinger. And he seems to have found religion: the last painting in the show, from 1939, depicts a giant St. Christopher with the Christ child on his shoulder, forging the waters between two shores that might almost have been painted by the 16th-century German Albrecht Altdorfer. He painted until his death in 1969, at the age of 77.

The etchings of “Der Krieg” get the Neue Galerie’s Dix retrospective off to a harrowing start. Displayed double-hung in their own gallery, they bear down on us relentlessly. It is a bit like being in the trenches yourself, especially given today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The prints show us soldiers with prostitutes or with one another, dancing in canteens, crouching in foxholes, clamoring across no man’s land, playing cards in the trenches (a sinister depiction of the hierarchy of strong and weak among enlisted men). Most of all Dix delivers the dead and dying in unstinting detail: horrific wounds, landscapes made of bodies and more bodies. Some are strung on barbed wire; others belong to civilians blown out of their beds by aircraft bombs. There are also bones, frozen, clawlike hands and, repeatedly, skulls — dead faces becoming skulls, worm-infested skulls and, in the final print, two skull-heads that seem to be attacking each other, a final testament to the futile unending self-destruction of war. Part of what makes the prints so riveting is their continual experimentation. Nearly every etching shows you a different side of the medium. Especially memorable is “Mealtime in the Trench,” with its striking contrast of acid-bitten, almost irradiated decay and the dark, densely lined form of a lone soldier.

In terms of intensity and coherence, the “War” is this show’s strongest gallery. There are plenty of riveting works in the rest of the display of course, but they come along one at a time, almost randomly without much sense of structure or curatorial oversight. For example “Memory of the Halls of Mirrors in Brussels,” the show’s only example of Dix’s raging Cubo-Expressionist works from 1920, is crammed into a small dark gallery with the etchings that Dix made prior to “Der Krieg.” It depicts a cackling nude courtesan on the knee of a debauched German soldier; they are highlighted against a silver background that throws no less than six reflections of them from various angles, including one showing the woman’s engorged genitalia.

In many ways Dix looked fresher and more imposing in the “Glitter and Doom” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art two years ago. He is especially hurt here by a shortage of black- chalk and pencil drawings. But the show might have gained immeasurably from a chronological installation. It would have been shocking to see the hysterical “Memory of the Halls of Mirrors” with Dix’s other paintings from 1919-21, which are the most tender and the most tenderly painted in the show.

One problem is that this exhibition is the first to be organized by Olaf Peters, an art historian at the University Halle-Wittenberg and a scholar in 20th-century German art (although he has overseen an excellent catalog for the show that is now the only full-dress Dix monograph in English that is currently in print).

The larger problem may be the Neue Galerie itself: the limits of its gallery space, a lack of clout that stalls major loans, and perhaps simply the lack of competition where 20th-century German art is concerned. The Neue may be a gift to New York, but it also something of a monopoly, which is never healthy. Dix’s achievement deserves a bigger museum. This show leaves us to piece together his wildness as best we can. There are wonderful rewards, but the first Dix retrospective in North America will also be the last for a while. It should have been overwhelming.

(click to enlarge)

"Parents of the Artist," oil on canvas by Otto Dix, 1921; in the Öffentliche … (credit: Courtesy of the Offentliche Kunstsammlung and the Emanuel Hoffman-Stiftung, Basel, Switz.; photograph, Hans Hinz)

"Parents of the Artist," oil on canvas by Otto Dix, 1921; in the Öffentliche … (credit: Courtesy of the Offentliche Kunstsammlung and the Emanuel Hoffman-Stiftung, Basel, Switz.; photograph, Hans Hinz)

Always Outrageous, Frequently Disturbing

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

“Mealtime in the Trench,” by Otto Dix, part of a retrospective of the artist’s works at the Neue Galerie. Dix was born in 1891 in Germany and saw action in World War I. More Photos >

How German was Otto Dix? The question echoes through the retrospective of Dix’s unforgiving art, the first show of its kind ever held in North America, at the Neue Galerie. The answer delivered by this completely engrossing yet sadly flawed exhibition is: deeply, madly, truly.

Multimedia

Blog

ArtsBeat

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

Otto Dix Foundation, Vaduz, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A retrospective of Otto Dix’s work, featuring “Brothel Matron/Puffmutter,” continues at the Neue Galerie. More Photos »

There are many sides to Dix, the son of an ironworker, whose talent for drawing was spotted early and led to study in an art academy in Dresden, with its great museums. In the 1920s he was invited to paint Hans Luther, a chancellor of the Weimar Republic. But he not only painted very different subjects, like prostitutes and crime scenes, he did so in ways that pushed his materials to the limit. His 1923 watercolor of a brothel matron verges on automatism. Elsewhere he borrowed from folk art, as with the quasi-naïve “Sunday Stroll” (1922) and its nuclear family; its members seem to swing from invisible strings like puppets.

As German painters often still do, Dix believed that the medium’s entire history — especially the German part — was available for his use. He painted in the small-brush smooth-surface manner of Albrecht Dürer and looked to Lucas Cranach for inspiration. With contemporaries like Christian Schad, he contributed to a perverse new style of realist painting, called the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) that emerged in 1925. By then he had already presented “The Skat Players,” a scathing 1920 Cubo-Expressionist collage-painting of postwar German amputees playing cards, at the landmark exhibition that the Dadaists staged in Berlin that year. That work is not here, but a small, bristling, tightly wound study conveys some of its vehemence; it is, unfortunately, one of the few pencil drawings included in this version of the show, organized with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where it will be somewhat larger.

Dix portrayed a multitude of Germanic types — from stoic farmers to limbs-akimbo Weimar demimondaines — as surely as the German photographer August Sander, often with the same penchant for capturing the Lutheran dignity of his subjects. But Dix, who was born in 1891, 15 years after Sander, and saw action in World War I, tended toward something less generous and more freakish. I doubt that Sander would have considered titling an image “Dedicated to Sadists,” as Dix did with a 1922 watercolor. He insinuated all manner of sly caricature, disgust and fury into many of his renderings. In addition to the horribly disfigured faces of war veterans, he also liked to depict, usually in watercolor and ink, the mutilated bodies of murdered women, victims of lustmord, or sexual murder.

There are numerous half-nude female models, signaling an unrepentant, usually unflattering fixation on female breasts; Dix often seems to have equated women with dumbness, whether brute or weak. But he could be intermittently sympathetic, especially concerning the downtrodden or the creative, as evidenced by early portraits like “Working-Class Boy,” which calls to mind Alice Neel’s paintings, and “Unemployed Man,” and by later ones of the poet Iwar von Lücken and the philosopher Max Scheler. A borderline case is the rarely exhibited “Two Children” from 1921, whose subjects seem innocent and open, despite strangely deformed features, and is more Diane Arbus than Neel.

Dix himself, who appears in several photographs early in the exhibition, three taken by his friend Hugo Erfurth and one by Sander himself, looked impeccably German — or Aryan as it would soon be called. A dandyish dresser, he was lean and fair-haired, with high cheek bones and narrow, penetrating eyes. Depending on how he cut and combed his hair, he resembled a Holbein portrait, an international (or Nazi) spy or an ascetic artist.

Dix’s self-portraits could flatter. “Self-Portrait with Nude Model” (1923) features a chiseled and smartly clothed Dix with slicked-back hair and at his side a curvy, slightly dopey-looking woman, her hair frazzled — although she has been awarded the luminous eyes of a seer. (So has “Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann” from 1920.) Yet he could also be as hard on himself as on anyone else. In a black-chalk drawing from 1917, he has long, sharp eye-teeth and a demonic vampire look. In “The Artist’s Family” (1927), painted a decade later, his wife, daughter and infant son fill the frame, while he seems to intrude from the right, like a handyman with bad teeth who usually keeps to the barn.

As with most German artists of his generation, Dix’s formative experience was World War I. He emerged from nearly four years in the trenches physically unscathed but psychically scarred. He attempted exorcism with “Der Krieg” (“The War”), a suite of 50 mostly masterly etchings published by Nierendorf in 1924. They convey a searing sense of the physical horror of war — most prominently wounded and rotting flesh — that remains unmatched in the history of art.

When the Nazis loomed, Dix closed one eye, made satiric references and also turned to images of mothers dandling or nursing infants, although painting women sincerely was hardly his forte. And when the Nazis came to power he was quickly dismissed from his teaching position at the Dresden academy. He was included in the famous 1937 degenerate art exhibition, and the Nazis ultimately impounded 260 of his works from German collections. Dix went into internal exile on Lake Constance. There he took to painting hyper-detailed landscapes that sometimes leaned toward Caspar David Friedrich, sometimes toward Breughel tinged with some of the weirdness of Max Klinger. And he seems to have found religion: the last painting in the show, from 1939, depicts a giant St. Christopher with the Christ child on his shoulder, forging the waters between two shores that might almost have been painted by the 16th-century German Albrecht Altdorfer. He painted until his death in 1969, at the age of 77.

The etchings of “Der Krieg” get the Neue Galerie’s Dix retrospective off to a harrowing start. Displayed double-hung in their own gallery, they bear down on us relentlessly. It is a bit like being in the trenches yourself, especially given today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The prints show us soldiers with prostitutes or with one another, dancing in canteens, crouching in foxholes, clamoring across no man’s land, playing cards in the trenches (a sinister depiction of the hierarchy of strong and weak among enlisted men). Most of all Dix delivers the dead and dying in unstinting detail: horrific wounds, landscapes made of bodies and more bodies. Some are strung on barbed wire; others belong to civilians blown out of their beds by aircraft bombs. There are also bones, frozen, clawlike hands and, repeatedly, skulls — dead faces becoming skulls, worm-infested skulls and, in the final print, two skull-heads that seem to be attacking each other, a final testament to the futile unending self-destruction of war. Part of what makes the prints so riveting is their continual experimentation. Nearly every etching shows you a different side of the medium. Especially memorable is “Mealtime in the Trench,” with its striking contrast of acid-bitten, almost irradiated decay and the dark, densely lined form of a lone soldier.

In terms of intensity and coherence, the “War” is this show’s strongest gallery. There are plenty of riveting works in the rest of the display of course, but they come along one at a time, almost randomly without much sense of structure or curatorial oversight. For example “Memory of the Halls of Mirrors in Brussels,” the show’s only example of Dix’s raging Cubo-Expressionist works from 1920, is crammed into a small dark gallery with the etchings that Dix made prior to “Der Krieg.” It depicts a cackling nude courtesan on the knee of a debauched German soldier; they are highlighted against a silver background that throws no less than six reflections of them from various angles, including one showing the woman’s engorged genitalia.

In many ways Dix looked fresher and more imposing in the “Glitter and Doom” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art two years ago. He is especially hurt here by a shortage of black- chalk and pencil drawings. But the show might have gained immeasurably from a chronological installation. It would have been shocking to see the hysterical “Memory of the Halls of Mirrors” with Dix’s other paintings from 1919-21, which are the most tender and the most tenderly painted in the show.

One problem is that this exhibition is the first to be organized by Olaf Peters, an art historian at the University Halle-Wittenberg and a scholar in 20th-century German art (although he has overseen an excellent catalog for the show that is now the only full-dress Dix monograph in English that is currently in print).

The larger problem may be the Neue Galerie itself: the limits of its gallery space, a lack of clout that stalls major loans, and perhaps simply the lack of competition where 20th-century German art is concerned. The Neue may be a gift to New York, but it also something of a monopoly, which is never healthy. Dix’s achievement deserves a bigger museum. This show leaves us to piece together his wildness as best we can. There are wonderful rewards, but the first Dix retrospective in North America will also be the last for a while. It should have been overwhelming.

沒有留言:

張貼留言