| 小原古邨 (おばら こそん) | |

|---|---|

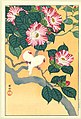

からすうり

| |

| 生誕 | 小原又雄 1877年2月9日 金沢市 |

| 死没 | 1945年1月4日(67歳) 東京都 |

| 墓地 | 仰西寺(金沢市) 北緯36度33分22秒西経136度40分17秒 |

| 国籍 | 日本 |

| 著名な実績 | 新版画 |

来歴[編集]

石川県金沢市に父・為則と母・そとの三男として生まれる。本名は小原又雄。英文表記では「Ohara」だが、実際には「おばら」と濁音だという[1]。古邨、祥邨、豊邨と号した。小原家は加賀藩に仕える本多家(図書家)の家臣で、父為則はその右筆だった。

画業[編集]

小原又雄は1890年代初頭(明治23年頃)、東京へ出て、花鳥画を得意にしていた鈴木華邨に師事して日本画を習得、やがてアーネスト・フェノロサの指導のもと、まず「古邨」と号して肉筆画の花鳥画を描き、共進会に出品もしている。1899年(明治32年)から日本絵画協会主催の展覧会、共進会展に上村松園、小林古径、竹内栖鳳などと並んで出品する。1899年(明治32年)10月、第7回日本絵画協会・第2回日本美術院連合絵画共進会展で「寒月」で3等褒状を与えられ、1900年(明治33年)10月)から1902年(明治35年)3月までの期間に第9回共進会展「花鳥獣(四種)」、第10回共進会展「からすうり」、第11回共進会展「嵐」、第12回共進会展では「花鳥百種」ですべて2等褒状を得るといったように輝かしい活躍をした。1903年(明治36年)高橋鐵太郎著 『海洋審美論』では挿絵を描き、その序文で「当時青年画家中に於て前途有望の聞こえある小原古村(ママ)」[2]とあり、頭角を表しつつある古邨の様子が伺える。

そのようななか、順調に日本画家としての道を歩み始めた古邨に転機が訪れる。東京帝国大学・東京美術学校の教授をしていた当時、東京帝室博物館の顧問でもあったフェノロサに勧められて、主としてヨーロッパ向けの輸出用の色摺り木版画の下絵を描き始めると、1905年(明治38年)から版元の松木平吉 (5代目) (大黒屋平吉)と協力して「古邨」の号で木版画による花鳥画を発表した。なお、松木平吉のほか、 秋山滑稽堂、西宮与作からも花鳥画を版行している。

画号は明治期の「古邨」[3]、1926年(昭和元年)に渡辺版画店発行の作品に「祥邨」[4]を用いて以降、酒井好古堂と川口商会の共同出版[5]では「豊邨」と号して、花鳥画及び動物画の木版下絵を発表し続けた。1932年(昭和7年)4月、渡辺版画店主催で開催された「第3回現代創作木版画展覧会」に「金魚」[6]、「波に千鳥」[6]など多くの作品を出品している。この展覧会にはほかに、伊東深水、川瀬巴水、高橋松亭、伊藤孝之、上原古年、織田一磨、名取春仙、エリザベス・キースら多くの新版画の作家による木版画が展示された。

渡辺版画店から出した花鳥版画は、古邨と彫師、摺師の卓越した職人技が生み出した見事な木版画であり、優れた美術作品として海外のコレクターの目を引き[7]、『Times』誌に作品が掲載されるなど、その作品は欧米で人気を集めている[8]。

1945年(昭和20年)に東京の自宅で死去した。67歳。墓は金沢市の仰西寺。

画号と時代[編集]

1912年(大正元年)に「祥邨」と改号してから1926年(昭和元年)までの間は肉筆画を描いていたといわれるが、大正から昭和初期に「古邨」と款する新版画作品「蓮」(松木平吉版)、「狐」(渡辺版)があり、大黒屋との関係が明治期のみであったのか、あるいは大正以降も「古邨」の号を併用、大正期に肉筆画のみでなく版下絵も描いたのかは検討を要す。なお花鳥版画は渡辺版画店においても続け、祥邨号の作品には後摺もある。

展覧会[編集]

版画の作品数は、およそ550件[9]とされ、国内のまとまった収集は原安三郎コレクション[10]、太田記念美術館[11]、平木浮世絵美術館他がある。古邨による版画の写生に基づきながら写実の枠にとどまらず、物語をこめた作風[12][13]は海外において特に高い評価を得ており[14][15]、1933年(昭和8年)のワルシャワ国際版画展覧会には長谷川清、深水、巴水らの版画とともに、木版画「柘榴におうむ」を出品。

2001年(平成13年)にはアムステルダム国立美術館において、日本人作家として初めてとなる大規模な回顧展[注釈 1]が開催され、同館所蔵の小原古邨による日本画及び木版画180点が展覧された。訪日もして精力的に収集した画商ロバート・ムラー(アメリカ)[17][14]は、生前、収集品を展覧会へ貸し出して新版画の魅力を広めようとしており、古邨を含む新版画と関連資料およそ4000点をアーサー・M・サックラー・ギャラリーにまとめて遺贈[18][注釈 2]、オランダにはJan Perrée コレクション[22]、ハンガリーには国立美術大学[23]の収集品があるなど欧米の美術館やコレクターによって多数、所蔵されている[13][15]。

国内初のまとまった回顧展は2018年(平成30年)に茅ヶ崎市美術館が開き、原安三郎コレクションから摺と保存の優れた230点[24]を初公開し小原の遺族から借り受けた[25]祥邨・豊邨号の作品と館蔵品を加えた[26]。翌2019年(平成31年)には江戸の浮世絵の技法を深めようとした古邨の軌跡に着目し[11]、太田記念美術館で動物の生態をとらえた手書きのデッサンや、水彩画のような色の調子を得るまでの試し摺りを交えて150点が展覧されている[27]。

作品[編集]

- 古邨

- 「雁」 滑稽堂 (明治後期) アーサー・M・サックラー・ギャラリー所蔵

- 「樹上の鷺」 同上 (明治後期) 同上

- 「雛鳥」 松木平吉 (明治後期) 同上

- 「蓮」 同上 (大正から昭和初期) 同上

- 「狐」 渡辺版画店 (大正から昭和初期) 同上

- 「雁」 同上 (1926年(昭和元年))

- 祥邨

- 豊邨

- 「オカメインコ」 川口版 (昭和初期)

- 「猫と金魚」祥邨[6]、「紫陽花に雀」、「睡蓮」、「ギボウシの花」、「藤の花」

ART

Ohara Koson: Bringing ukiyo-e back to life

BY MARTIN LAFLAMME

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

By the early 1900s, Japan’s rich tradition of woodblock printing was on its deathbed. The cornerstone of commercial publishing for hundreds of years, it had also spawned the floruit of ukiyo-e, one of the glories of old Edo merchant culture.

As Japan opened to the West and publishers gained access to foreign advanced technology, however, the print industry underwent a massive revolution. Suddenly, images could be produced quickly, cheaply and in much larger quantities. By comparison, woodcutting was a laborious technique that, in the case of ukiyo-e prints, could require the carving of a dozen blocks before a single image could be completed. It was a slow and cumbersome process, one that was utterly unsuited to a society rushing headlong into modernity.

Yet, just as woodblock printing seemed destined for the dustheap, two new artistic trends arose from the mid aughts of the new century to give the art form renewed purpose.

The first, which emerged in 1904, was the “creative print” movement, known as sōsaku-hanga, which emphasized personal experimentation. This generally found favor with Western-trained artists who looked to Paris for inspiration and who insisted upon retaining control over all aspects of a print’s creation — from the original design and carving of the blocks to the choice of paper and the final impression.

The second, usually dated to 1915, was the “new print” movement, or shin-hanga, whose adherents worked much like the old ukiyo-e masters. Artists of this persuasion usually limited their contribution to a design, albeit one that was often based on an original painting of their own, which was then passed on to a publisher for approval. If the latter was satisfied, he would hire a craftsman to carve the blocks and then hand these over to a printer who brought the final image to life. In other words, it was a highly collaborative process. It was also a small affair: between 1915 and 1940 there were only around 35 artists working in the genre.

One of these was Ohara Koson (1877-1945). He was neither the most successful nor the best-known — Hasui Kawase (1883-1957), Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) and Shinsui Ito (1898-1972) are usually considered the movement’s standard-bearers — but he left a large body of work that has only come to be fully appreciated in the past 20 years.

Illustrating this critical and popular revival, Koson is now the subject of a retrospective at the Ota Memorial Museum of Art, the first exhibition in Tokyo to cover his entire career as a print designer. The second installment of the show can be viewed until March 24.

Scholars believe that Koson created up to 500 different prints, the majority in a single but highly productive decade, between 1926 and 1935. This flurry of activity notwithstanding, we know very little about his life. This is surprising, since dozens of specialized arts journals were in circulation during these years, to say nothing of a gaggle of print media.

Why is there so little about Koson on the public record? In a recent interview with the Japan Times, Kenji Hinohara, chief curator at the Ota Memorial Museum of Art, suggested an explanation: There has been comparatively little academic research on Koson.

“It is possible we will learn more in the future,” he opines.

For now, only the basic contours of Koson’s life have been established with some clarity. He was born in Ishikawa Prefecture, on the west coast of Japan, and he trained at a local technical school. He then apprenticed with Suzuki Kason, a specialist of kachōga (flowers-and-birds painting), from whom he inherited much of his aesthetics and sensibility — Koson showed little interest for the popular subject of beautiful women in various states of deshabille.

In the mid to late 1890s, he moved to Tokyo, where Suzuki helped him gain entry into the capital’s arts circles. Perhaps under the influence of the art historian Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908), who championed the importance of traditional Japanese arts, Koson dabbled in woodblock printing. Eventually, however, he chose to focus on nihonga, a late 19th-century painting genre that upheld Japanese styles and techniques, often blending them with Western influences in a highly eclectic manner.

Alas, Koson never quite made it as a painter. “He was not highly esteemed as a nihonga artist,” says Hinohara, which might also explain why so few of his paintings have survived.

In 1926, apparently realizing he was going nowhere, or perhaps just needing to secure a stable income, Koson, then just shy of 50, returned to prints. This time, he stuck to it.

It was a wise decision. Koson was not very popular in Japan but he developed a keen foreign clientele, particularly in the United States. He was part of a small group of shin-hanga artists whose work was broadly exhibited overseas and whose subject matter appealed to foreigners’ tastes and curiosity for an exotic Far East. His prints were also affordable and thus easily collectable.

Woodblock printing never recovered the status it held in its heyday in the first half of the 19th century, when Utagawa Hiroshige and Utagawa Kuniyoshi were pushing its limits to heroic effect. But as a medium for artistic expression, it did not disappear, despite frequent rumors of its imminent demise. Koson and his ilk made sure of that.

沒有留言:

張貼留言