Architecture | 24.10.2011

Memory is essential to architecture, says Daniel Libeskind

Deutsche Welle: Mr. Libeskind, you're building, or you've built the addition to the Military Museum in Dresden. Your family suffered from the Nazis. How does that go together?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I think the story of the Military History Museum in Dresden is a story of change - change of Germany. This armory, which was renovated and where a new structure had been inserted, really tells a story of the transformation of the armory, which was also a Saxon museum, a Nazi museum, a Soviet museum, an East German museum - and of course, in a democracy, the military is very important.

A military museum is important in a democracy because every citizen has the responsibility to understand what is going on. So it's not just a museum of conflicts, of weaponry, of the hardware, but it's a reflection on violence and reflection on the city of Dresden, which itself suffered in World War II. So it's a major new encounter with military history and, just as the new wedge-like form pushes through the opacity and the darkness and the rigidity of the armory to the outside, so does Germany push through its old regimes, its autocratic regimes, totalitarian regimes towards a new window of freedom and democracy of a united Germany.

How did you try to have the building fit together with what's inside the museum?

Libeskind's Dresden design depicts an interrupted chronology in the history of warI worked very closely with the exhibition designers from the very beginning. But there are two aspects. I restored the armory. It was very run-down and it was very abused when it was the East German kind of military museum. So I restored it lovingly (…) but I also cut through it a completely new space, which is a new totally unprecedented space. It's not a space just for more of the same. It's a space which deliberately interrupts that chronology that ended at World War II and presents questions to a democratic society, to the republic, to families, to children: What do these conflicts means? How can we steer them to a better place? How can we avoid wars? And what do they mean for society in a democracy?

Libeskind's Dresden design depicts an interrupted chronology in the history of warI worked very closely with the exhibition designers from the very beginning. But there are two aspects. I restored the armory. It was very run-down and it was very abused when it was the East German kind of military museum. So I restored it lovingly (…) but I also cut through it a completely new space, which is a new totally unprecedented space. It's not a space just for more of the same. It's a space which deliberately interrupts that chronology that ended at World War II and presents questions to a democratic society, to the republic, to families, to children: What do these conflicts means? How can we steer them to a better place? How can we avoid wars? And what do they mean for society in a democracy?

It's more an anti-war museum than a military museum, the way you're explaining it now?

I don't think it's an anti-war museum - of course, who's insane enough to be for a war? No one. But, military history is ongoing. We see that Germany, the United States, other countries are participating in conflicts around the world. So we have to understand what these conflicts mean in a democracy. These are no longer decisions made behind big walls, like in the old times, behind the walls of the armory, but they are really made in front of the public. And it is in the public interest and public importance to be participants in the decisions of an open and free government. And that's not really an anti-war museum, it's a museum that will inform the public, educate the public, create a continuity of what are the possibilities that prevent the kind of violence that we have seen all too often coming out of Germany in the 20th century.

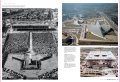

The opening of the edition to the military museum in Dresden coincides with the 10-year anniversary of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Many people feel that the building itself is more important than what's in it. How do you feel about that building today? Does it work the way you were hoping it should work back then?

I think museums have to work for their exhibitions. Now, when I was working at the Jewish Museum, of course, there were many changes. The museum changed its program, even its name, many times across time until it became the Jewish Museum Berlin. It's very different in the Military History Museum in Dresden because I worked from the very beginning on a very profound idea of what the museum should contain, what objects should be there, what stories are to be told. So they are two very different spaces. They address two very different programs, and, of course, they are very different buildings for the public.

The Jewish Museum in Berlin is celebrating its 10th anniversary

The Jewish Museum in Berlin is celebrating its 10th anniversary

You do a lot of museums about remembering, which museums are usually about. But how do you translate remembering into architecture?

Well, I think without memory we would not know where we are going or who we are. So memory's not just a little sideline for architecture, it's the fundamental way to orient the mind, the emotions, the soul. And, of course, how to engage that memory through the visceral experience, not just the intellectual experience, but to the full emotional experience of a human being. That's what architecture is and that can be done through light, through proportions, through acoustics, through materials, through the language of architecture.

Do you like working in Germany?

I do like working [in Germany], very much.

Why?

I think Germany is a very progressive country. It has a youthful spirit. It has a difficult history which will never go away. But Germany is a country that has also faced how difficult history is and hasn't just put it under a carpet but is dealing with it and I think that's something very admirable. Not everyone would be able to face those horrors and yet see that there's a hope, see that there's a new generation, that there's something to be learned from it, something never to be repeated again, and to extend the possibilities of human beings.

Interview: Max Hofmann, DW-TV, New York

Editor: Kate Bowen