His mutilated body was found in a vacant lot in Ostia, a suburb of Rome,

in 1975. The assumed killer (who later recanted his confession) was a

17-year-old hustler he had picked up.

His colleague Michelangelo Antonioni remarked that Pasolini had become

“the victim of his own characters.” Completed weeks before he died, at

53, Pasolini’s last movie, “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” an

unrelentingly brutal adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s catalog of

degradation and torture, came to be viewed, all too neatly, as a death

wish.

In other crucial ways, though, the meaning of Pasolini remains

undecipherable, ambiguous, suspended. A lapsed Catholic who never lost

his religious worldview and a lifelong Marxist who was expelled from the

Communist Party for being gay, Pasolini was an artist and thinker who

tried not to resolve his contradictions but rather to embody them fully.

With his gift for polemics and taste for scandal, he was routinely

hauled up on blasphemy and obscenity charges and attacked by those on

the left and the right.

Evoking the feverish sprawl of Pasolini’s output, these events make the

implicit case that it is difficult to consider any of his works in

isolation.

“It’s very hard to put one label on him,” said Jytte Jensen, the curator

who organized the retrospective. “He had many essential roles in

Italian society, and he was always searching, completely open to

different ways of looking at things and not afraid to say he was

mistaken.”

Coming to film from literature, Pasolini viewed cinema as an expressive

and flexible form, a language that, as he put it, “writes reality with

reality.” Just as he wrote poetry and fiction in a variety of dialects,

his movies cycled through a range of styles and tones. The reactions to

them were often divided, rarely predictable.

The clearest thread running through Pasolini’s movies is his mounting

disgust with the modern world. He saw Italy’s postwar boom as an

irreversible blight, turning the masses into mindless consumers and

erasing local cultures. (For Pasolini difference was always to be

protected and flaunted.)

At the Modern over the next two weeks every screening will begin with a

clip of Pasolini discussing the film at hand. Ms. Jensen said these

personal introductions were in keeping with the immediacy of his work.

“When you’re sitting in a theater watching a Pasolini film,” she said,

“you feel he’s speaking directly to you.”

The Pasolini film retrospective runs through Jan. 5 at the Museum of

Modern Art; moma.org. A Pasolini cinematic installation runs through

Jan. 7 at MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, Queens;

momaps1.org. A show of portraits by Pasolini is on view through Jan. 5

at Location One, 26 Greene Street, near Grand Street, SoHo;

location1.org.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Pier Paolo Pasolini |

|

| Born |

March 5, 1922

Bologna, Italy |

| Died |

November 2, 1975 (aged 53)

Ostia, Rome, Italy |

| Occupation |

Film director, novelist, poet, intellectual, journalist, linguist, philosopher |

| Notable work(s) |

Accattone

Salò

The Gospel According to St. Matthew |

|

|

|

| Signature |

|

Pier Paolo Pasolini (

Italian pronunciation: [ˈpjɛr ˈpaolo pazoˈlini]; March 5, 1922 – November 2, 1975) was an

Italian film director,

poet,

writer and

intellectual. Pasolini distinguished himself as a poet,

journalist,

philosopher,

linguist,

novelist,

playwright,

filmmaker,

newspaper and

magazine columnist,

actor,

painter and

political figure.

He demonstrated a unique and extraordinary cultural versatility,

becoming a highly controversial figure in the process. While his work

remains controversial to this day, in the years since his death Pasolini

has come to be valued by many as a visionary thinker and a major figure

in Italian literature and art. Influential American literary critic

Harold Bloom

considers Pasolini to be a major European poet and a major voice in

20th-century poetry, including his works in his collection of the

Western Canon.

Biography

Early life

Pasolini was born in Bologna, traditionally one of the most leftist of Italian cities. He was the son of a

lieutenant of the

Italian Army, Carlo Alberto, who had become famous for saving

Benito Mussolini's life during

Anteo Zamboni's

assassination attempt, and subsequently married an elementary school

teacher, Susanna Colussi, in 1921. Pasolini was born in 1922 and was

named after his paternal uncle. His family moved to

Conegliano in 1923 and, two years later, to

Belluno,

where another son, Guidalberto, was born. In 1926, Pasolini's father

was arrested for gambling debts, and his mother took the children to her

family's house in

Casarsa della Delizia, in the

Friuli region.

Pasolini began writing poems at the age of seven, inspired by the

natural beauty of Casarsa. One of his early influences was the work of

Arthur Rimbaud. In 1931, his father was transferred to Idria in the

Julian March (now

Idrija in

Slovenia);

[1] in 1933 they moved again to

Cremona in

Lombardy, and later to

Scandiano and

Reggio Emilia.

Pasolini found it difficult to adapt to all these moves, though in the

meantime he enlarged his poetry and literature readings (

Dostoyevsky,

Tolstoy,

Shakespeare,

Coleridge,

Novalis)

and left behind the religious fervour of his early years. In the Reggio

Emilia high school, he met his first true friend, Luciano Serra. The

two met again in Bologna, where Pasolini spent seven years while

completing high school: here he cultivated new passions, including

football. With other friends, including Ermes Parini, Franco Farolfi, Elio Meli, he formed a group dedicated to literary discussions.

In 1939 Pasolini graduated and entered the Literature College of the

University of Bologna, discovering new themes such as

philology and

aesthetics of

figurative arts.

He also frequented the local cinema club. Pasolini always showed his

friends a virile and strong exterior, totally hiding his interior

travail. He took part in the

Fascist government's culture and sports competitions. In 1941, together with

Francesco Leonetti,

Roberto Roversi

and others, he attempted to publish a poetry magazine, but the attempt

failed due to paper shortages. In his poems of this period, Pasolini

started to include fragments in

Friulan, which he had learned from his mother.

Early poetry

After the summer in Casarsa, in 1941 Pasolini published at his own expense a collection of poems in

Friulan,

Versi a Casarsa. The work was noted and appreciated by intellectuals and critics such as

Gianfranco Contini,

Alfonso Gatto and

Antonio Russi. His pictures had also been well received. Pasolini was chief editor of the

Il Setaccio ("The Sieve") magazine, but was fired after conflicts with the director, who was aligned with the

Fascist regime. A trip to Germany helped him also to discover the "provincial" status of

Italian culture

in that era. These experiences led Pasolini to rethink his opinion

about the cultural politics of Fascism and to switch gradually to a

Communist position.

In 1942, the family took shelter in Casarsa, considered a more tranquil place to wait for the conclusion of the

war, a decision common among Italian military families. Here, for the first time, Pasolini had to face the

erotic disquiet he had suppressed during his

adolescent years. He wrote: "A continuous perturbation without images or words beats at my temples and obscures me".

[citation needed]

In the weeks before the 8 September

armistice, Pasolini was

drafted. He was captured and imprisoned by the

Germans. He managed to escape disguised as a

peasant,

and found his way to Casarsa. Here he joined a group of other young

fans of the Friulan language who wanted to give Casarsa Friulan a status

equal to that of

Udine, the official regional standard. From May 1944 they issued a magazine entitled

Stroligùt di cà da l'aga. In the meantime, Casarsa suffered Allied bombardments and forced enrollments by the

Italian Social Republic, as well as

partisan activity.

Pasolini tried to remain apart from these events. He and his mother taught students unable to reach the schools in

Pordenone or

Udine. He experienced his first

homosexual love for one of his students. At the same time, a

Slovenian schoolgirl, Pina Kalč, was falling in love with Pasolini.

[citation needed]

On 12 February 1945 his brother Guido was killed in an ambush. Six days

later Pasolini and others founded the Friulan Language Academy (

Academiuta di lenga furlana). In the same year Pasolini joined the Association for the Autonomy of Friuli. He graduated after completing a final

thesis about

Giovanni Pascoli's works.

In 1946 Pasolini published a small

poetry collection,

I Diarii ("The Diaries"), with the Academiuta. In October he travelled to

Rome. The following May he began the so-called

Quaderni Rossi, handwritten in old school exercise books with red covers. He completed a drama in Italian,

Il Cappellano. His poetry collection,

I Pianti ("The cries"), was also published by the Academiuta.

Relationship with the Italian Communist Party

On 26 January 1947 Pasolini wrote a controversial declaration for the front page of the newspaper

Libertà:

"In our opinion, we think that currently only Communism is able to

provide a new culture." The controversy was partly due to the fact he

was still not a member of the

Italian Communist Party (PCI).

He was also planning to extend the work of the Academiuta to other

Romance language literatures and knew the exiled

Catalan poet,

Carles Cardó. After his adherence to the PCI, he took part in several demonstrations. In May 1949, Pasolini attended the Peace Congress in

Paris.

Observing the struggles of workers and peasants, and watching the

clashes of protesters with Italian police, he began to create his first

novel.

In October of the same year, Pasolini was charged with the corruption

of minors and obscene acts in public places. As a result, he was

expelled by the Udine section of the Communist Party and lost the

teaching job he had obtained the previous year in Valvasone. Left in a

difficult situation, in January 1950 Pasolini moved to Rome with his

mother.

He later described this period of his life as very difficult. "I came

to Rome from the Friulan countryside. Unemployed for many years;

ignored by everybody; driven by the fear to be not as life needed to

be". Instead of asking for help from other writers, Pasolini preferred

to go his own way. He found a job as a worker in the

Cinecittà studios and sold his books in the 'bancarelle' ("sidewalk shops") of Rome. Finally, through the help of the

Abruzzese-language poet

Vittorio Clemente, he found a job as a teacher in

Ciampino, a suburb of the capital.

In these years Pasolini transferred his Friulan countryside inspiration to Rome's suburbs, the infamous

borgate where poor

proletarian immigrants lived in often horrendous sanitary and social conditions.

Success and charges

In 1954, Pasolini, who now worked for the literary section of Italian

state radio, left his teaching job and moved to the Monteverde quarter,

publishing

La meglio gioventù, his first important collection of dialect poems. His first novel,

Ragazzi di vita (English:

Hustlers),

was published in 1955. The work had great success but was poorly

received by the PCI establishment and, most importantly, by the Italian

government. It initiated a lawsuit

[specify]

against Pasolini and his editor, Garzanti. Though totally exonerated of

any charge, Pasolini became a victim of insinuations, especially by the

tabloid press.

In 1957, together with

Sergio Citti, Pasolini collaborated on

Federico Fellini's film

Le notti di Cabiria, writing dialogue for the

Roman dialect parts. In 1960 he made his debut as an actor in

Il gobbo, and co-wrote

Long Night in 1943.

His first film as director and screenwriter is

Accattone

of 1961, again set in Rome's marginal quarters. The movie aroused

controversy and scandal. In 1963, the episode "La ricotta", included in

the collective movie

RoGoPaG, was censored and Pasolini was tried for offence to the Italian state.

During this period Pasolini frequently traveled abroad: in 1961, with

Elsa Morante and

Alberto Moravia to

India (where he went again seven years later); in 1962 to

Sudan and

Kenya; in 1963, to

Ghana,

Nigeria,

Guinea,

Jordan and

Israel (where he shot the documentary,

Sopralluoghi in Palestina). In 1970 he travelled again to

Africa to shoot the documentary,

Appunti per un'Orestiade africana.

In 1966 he was a member of the jury at the

16th Berlin International Film Festival.

[2]

In 1967, in Venice, he met and interviewed the American poet

Ezra Pound.

[3] They discussed about Italian movement

neoavanguardia, arts in general and Pasolini read some verses from the Italian version of Pound's

Pisan Cantos.

[3]

The late 1960s and early 1970s were the era of the so-called "student

movement". Pasolini, though acknowledging the students' ideological

motivations, thought them "anthropologically middle-class" and therefore

destined to fail in their attempts at revolutionary change. Regarding

the

Battle of Valle Giulia,

which took place in Rome in March 1968, he said that he sympathized

with the police, as they were "children of the poor", while the young

militants were exponents of what he called "left-wing fascism". His film

of that year,

Teorema, was shown at the annual

Venice Film Festival in a hot political climate. Pasolini had proclaimed that the Festival would be managed by the directors (see also

Works section).

In 1970 Pasolini bought an old castle near

Viterbo, several miles north of Rome, where he began to write his last novel,

Petrolio, which was never finished. In 1972 he started to collaborate with the extreme-left association

Lotta Continua, producing a documentary,

12 dicembre, concerning the

Piazza Fontana bombing. The following year he began a collaboration for Italy's most renowned newspaper,

Il Corriere della Sera.

At the beginning of 1975 Garzanti published a collection of critical essays,

Scritti corsari ("Corsair Writings").

Death

Pasolini was murdered by being run over several times with his own car, dying on 2 November 1975 on the beach at

Ostia, near

Rome. Pasolini was buried in Casarsa, in his beloved

Friuli.

Giuseppe Pelosi, a seventeen-year-old

hustler,

was arrested and confessed to murdering Pasolini. Thirty years later,

on 7 May 2005, he retracted his confession, which he said was made under

the threat of violence to his family. He claimed that three people

"with a southern accent" had committed the murder, insulting Pasolini as

a "dirty communist".

[4]

Other evidence uncovered in 2005 pointed to Pasolini's having been

murdered by an extortionist. Testimony by Pasolini's friend Sergio Citti

indicated that some of the rolls of film from

Salò had been stolen, and that Pasolini had been going to meet with the thieves after a visit to

Stockholm, November 2, 1975.

[5][6][7][8]

Despite the Roman police's reopening of the murder case following

Pelosi's statement of May 2005, the judges charged with investigating it

determined the new elements insufficient for them to continue the

inquiry.

Political views

Pasolini generated heated public discussion with controversial

analyses of public affairs. For instance, during the disorders of 1969,

when the

autonomist

university students were carrying on a guerrilla-like uprising against

the police in the streets of Rome and all the leftist forces declared

their complete support for the students, describing the disorders as a

civil fight of proletariat against the System, Pasolini, alone among the

communists, declared that he was with the police; or, more precisely,

with the policemen. He considered them true proletariat, sent to fight

for a poor salary and for reasons which they could not understand,

against pampered boys of their same age, because they had not had the

fortune of being able to study, referring to

poliziotti figli di proletari meridionali picchiati da figli di papà in vena di bravate (lit.

policemen, sons of proletarian southerners, beaten up by arrogant daddys' boys). This statement, however, did not stop him from contributing to the autonomist

Lotta continua movement.

Pasolini was also an ardent critic of

consumismo, i.e.

consumerism,

which he felt had rapidly destroyed Italian society in the late

1960s/early 1970s. He was particularly concerned about the class of the

subproletariat, which he portrayed in

Accattone,

and to which he felt both humanly and artistically drawn. Pasolini

observed that the kind of purity which he perceived in the

pre-industrial popular culture was rapidly vanishing, a process that he

named

la scomparsa delle lucciole (lit. "

the disappearance of glow-worms"). The

joie de vivre of the boys was being rapidly replaced with more

bourgeois ambitions such as a house and a family. He described the

coprophagia scenes in

Salò

as a comment on the processed food industry. He often described

consumeristic culture as "unreal", as it had been imposed by economic

power and had replaced Italy's traditional peasant culture, something

that not even

fascism

had been able to do. In one interview, he said: "I hate with particular

vehemency the current power, the power of 1975, which is a power that

manipulates bodies in a horrible way; a manipulation that has nothing to

envy to that performed by Himmler or Hitler."

He was angered by economic

globalization and cultural domination of the

North of Italy (around

Milan) over other regions, especially the South.

[citation needed] He felt this was accomplished through the power of

TV. He opposed the gradual disappearance of Italian

dialects by writing some of his poetry in

Friulan, the regional language of his childhood. Despite his left-wing views, Pasolini opposed the liberalization of

abortion laws.

[9]

Sexuality

The

LGBT encyclopedia states the following regarding Pasolini's

homosexuality:

While openly gay from the very start of his career (thanks to a gay

sex scandal that sent him packing from his provincial hometown to live

and work in Rome), Pasolini rarely dealt with homosexuality in his

movies. The subject is featured prominently in Teorema (1968),

where Terence Stamp's mysterious God-like visitor seduces the son and

father of an upper-middle-class family; passingly in Arabian Nights (1974), in an idyll between a king and a commoner that ends in death; and, most darkly of all, in Salò (1975), his infamous rendition of the Marquis de Sade's compendium of sexual horrors, The 120 Days of Sodom.[10]

In 1963 he met "the great love of his life," fifteen-year-old

Ninetto Davoli whom he later cast in his 1966 film

Uccellacci e uccellini (literally

Bad Birds and Little Birds but translated in English as

The Hawks and the Sparrows),

Pasolini became his mentor and friend. "Even though their sexual

relations lasted only a few years, Ninetto continued to live with

Pasolini and was his constant companion, as well as appearing in six

more of his films."

[11]

Works

Pasolini's first novel

Ragazzi di vita (1955) dealt with the Roman

lumpenproletariat. The resulting

obscenity charges against him were the first of many instances where his

art provoked legal problems.

Accattone (1961), also about the

Roman underworld, also provoked controversy with conservatives, who demanded stricter

censorship.

He then directed the black-and-white

The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). This film is a cinematic adaptation of the life of

Jesus (

Enrique Irazoqui).

While filming it, Pasolini vowed to direct it from the "believer's

point of view", but later said that upon viewing the completed work, he

realized he had instead expressed his own beliefs.

In his 1966 film,

Uccellacci e uccellini (literally

Bad Birds and Little Birds but translated in English as

The Hawks and the Sparrows), a picaresque - and at the same time mystic - fable, he hired the great Italian

comedian Totò to work with one of his preferred "naif" actors,

Ninetto Davoli. It was a unique opportunity for Totò to demonstrate that he was a great dramatic actor as well.

In

Teorema (

Theorem, 1968), starring

Terence Stamp as a mysterious stranger, he depicted the sexual coming-apart of a

bourgeois family (later repeated by

François Ozon in

Sitcom and

Takashi Miike in

Visitor Q).

Later movies centered on sex-laden

folklore, such as

Boccaccio's

Decameron (1971) and

Chaucer's

Canterbury Tales (1972) and

Il fiore delle mille e una notte (literally

The Flower of 1001 Nights, released in English as

Arabian Nights, 1974). These films are usually grouped as the

Trilogy of Life.

His final work,

Salò (

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,

1975), exceeded what most viewers could then stomach in its explicit

scenes of intensely sadistic violence. Based on the novel

120 Days of Sodom by the

Marquis de Sade, it is considered his most controversial film. In May 2006,

Time Out's Film Guide named it the Most Controversial Film of all time.

Legacy

As a director, Pasolini created a

picaresque neorealism, showing a sad reality. Many people did not want to see such portrayals in artistic work for public distribution.

Mamma Roma (1962), featuring

Anna Magnani

and telling the story of a prostitute and her son, was an affront to

the morality of those times. His works, with their unequaled poetry

applied to cruel realities, showing that such realities are less distant

from us than we imagine, made a major contribution to change in the

Italian psyche.

[citation needed][12]

The director also promoted in his works the concept of "natural

sacredness," the idea that the world is holy in and of itself. He

suggested there was no need for spiritual essence or supernatural

blessing to attain this state. Pasolini was an avowed

atheist.

General disapproval of Pasolini's work was perhaps caused primarily

by his frequent focus on sexual mores, and the contrast between what he

presented and publicly sanctioned behavior. While Pasolini's poetry

often dealt with his same-sex love interests, this was not the only, or

even main, theme. His interest and approach to Italian dialects should

also be noted. Much of the poetry was about his highly revered mother.

As a sensitive and intelligent man, he depicted certain corners of the

contemporary reality as few other poets could do. His poetry was not as

well known as his films outside Italy.

[citation needed][13]

He had also developed a philosophy of the language mainly related with his studies on Cinema;

[14]

this theorical and critical activity was another debated topic by the

acclimated cultural background as the collected articles still available

today show pretty clearly.

[12][15][16]

These studies can be considered as the foundation of his artistic

point of view, as a matter of fact they basically point out two aspects:

the language - as English, Italian, dialect or other - is a rigid

system in which the human thought is trapped as well; the cinema is the

written language of reality which, like any other written language,

enable man to see things from the point of view of truth.

[14]

His films won awards at the

Berlin Film Festival,

Cannes Film Festival,

Venice Film Festival, Italian National Syndicate for Film Journalists,

Jussi Awards, Kinema Junpo Awards, International Catholic Film Office and

New York Film Critics Circle.

Ebbo Demant directed the documentary

Das Mitleid ist gestorben about Pasolini.

In 2005

Stefano Battaglia recorded

Re: Pasolini in dedication to Pasolini.

Filmography

Feature films

All titles listed below were written and directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini unless stated otherwise. Although obviously

Oedipus Rex and

Medea are loosely based on plays by

Sophocles and

Euripides

respectively, significant liberties were taken with original texts and

titles do not credit anyone except Pasolini. The latter is also true in

the case of

St. Matthew.

Documentaries

Episodes in omnibus films

Bibliography

Narrative

Poetry

- La meglio gioventù (1954)

- Le ceneri di Gramsci (1957)

- L'usignolo della chiesa cattolica (1958)

- La religione del mio tempo (1961)

- Poesia in forma di rosa (1964)

- Trasumanar e organizzar (1971)

- La nuova gioventù (1975)

- Roman Poems. Pocket Poets #41 (1986)

Essays

- Passione e ideologia (1960)

- Canzoniere italiano, poesia popolare italiana (1960)

- Empirismo eretico (1972)

- Lettere luterane (1976)

- Le belle bandiere (1977)

- Descrizioni di descrizioni (1979)

- Il caos (1979)

- La pornografia è noiosa (1979)

- Scritti corsari (1975)

- Lettere (1940–1954) (Letters, 1940-54, 1986)

Theatre

- Orgia (1968)

- Porcile (1968)

- Calderón (1973)

- Affabulazione (1977)

- Pilade (1977)

- Bestia da stile (1977)

Notes

- ^ http://www.rtvslo.si/kultura/drugo/ste-vedeli-da-je-pier-paolo-pasolini-v-otrostvu-nekaj-casa-zivel-v-idriji/294028

- ^ "Berlinale 1966: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ a b http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jrwIbjwbT0o

- ^ Cataldi, Benedetto (2005-05-05). "Pasolini death inquiry reopened". bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Asesinato de Pasolini, nueva investigación" (in Italian). La Razón. La Razón. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Héctor Rivera (28). "Pasolini de nuevo" (in Italian). Sentido contrario. Grupo Milenio. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922 – 1975)" (in Italian). Cinematismo. Cinematismo. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:ouU8zYEgmXMJ:rassegnastampa.mef.gov.it/mefinternazionale/PDF/2010/2010-04-02/2010040215372121.pdf+muerte+de+pasolini-+rollos+robados&hl=es&gl=co&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESg_Hz3kNu-APpn4-A1D42JjsI01jWmCc2RU0zb8ji3iX5Me-8LlK1uyuIo3mo0-NebUSyoFpa3dPHTIiOtQfs1b07D-_EhM_NYQjqCIObthlxA86VQDWnhZ7wpjQmFbzWDkBQuy&sig=AHIEtbROrSJpidVdGjEyfEHWL7gELlXFTw

- ^ Petri Liukkonen, Ari Pesonen (2008). "Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975)". Books and Writers. Kuusankosken kaupunginkirjasto. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Ehrenstein, David (2005). Pasolini, Pier Paolo. glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture.

- ^ Ireland, Doug (2005-08-04). "Restoring Pasolini". LA Weekly (LA Weekly, LP). Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ a b Pasolini Pierr Paolo (1995) (in Italian). Il Caos (collected articles). Roma: Editori Riuniti.

- ^ Pasolini Pier Paolo (1996). Collected Poems. Noonday Press. ISBN 0-374-52469-6, 9780374524692.

- ^ a b Pasolini, Pier Paolo (1988-2005). Heretical empiricism. New Academia Publishing. ISBN 0-9767042-2-6, 9780976704225.

- ^ A. Covi (1971) (in Italian). Dibattiti sui film. Padova: Gregoriana.

- ^ A. Asor Rosa (1988) (in Italian). Scrittori e Popolo – il populismo nella letteratura italiana contemporanea. Torino: Gregoriana.

- ^ The translated English title is used infrequently.

- ^ "Berlinale 1972: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ^ "Berlinale 1972: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Arabian Nights". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

References

- Aichele, George. "Translation as De-canonization: Matthew's Gospel

According to Pasolini - filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini - Critical Essay."

Cross Currents (2002). FindArticles.

- Distefano, John. "Picturing Pasolini." Art Journal (1997).

- Eloit, Audrene. "Oedipus Rex by Pier Paolo Pasolini The Palimpsest:

Rewriting and the Creation of Pasolini's Cinematic Language." Literature Film Quarterly (2004). FindArticles.

- Fabbro, Elena (ed.). Il mito greco nell'opera di Pasolini. Atti del Convegno Udine-Casarsa della Delizia, 24-26 ottobre 2002. Udine: Forum (2004). ISBN 88-8420-230-2

- Forni, Kathleen. "A "cinema of poetry": What Pasolini Did to Chancer's Canterbury Tales." Literature Film Quarterly (2002). FindArticles.

- Frisch, Anette. "Francesco Vezzolini: Pasolini Reloaded." Interview, Rutgers University Alexander Library, New Brunswick, NJ.

- Green, Martin. "The Dialectic Adaptation."

- Greene, Naomi. Pier Paolo Pasilini: Cinema as Heresy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1990.

- Meyer-Krahmer, Benjamin. "Transmediality and Pastiche as Techniques

in Pasolini’s Art Production", in: P.P.P. - Pier Paolo Pasolini and

death, eds. Bernhart Schwenk, Michael Semff, Ostfildern 2005, p. 109 -

118

- Passannanti, Erminia. The Sacred Transgressed. Pasolini, the Roman Catholic Church and Secularity in the short film "La ricotta", Brindin Press (2009).

- Passannanti, Erminia. Il Cristo dell'Eresia. Sacro e censura nel cinema di Pier Paolo Pasolini, Joker (2009).

- Passannanti, Erminia. Deconstruction and redefinition of the Italian Catholic Identity in Pier Paolo Pasolini's La ricotta, in Italy on Screen: National Identity and Italian Imaginary, Lucy Bolton and Christina Siggers Manson (eds.), Series New Studies in European Cinema series, Peter Lang (2010).

- Pugh, Tison. "Chaucerian Fabliaux, Cinematic Fabliau: Pier Paolo Pasolini's I racconti di Canterbury.", Literature Film Quarterly (2004). FindArticles.

- Restivo, Angelo. The Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film. London: Duke UP, 2002.

- Rohdie, Sam. The Passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana UP, 1995.

- Rumble, Patrick A. Allegories of contamination: Pier Paolo Pasolini's Trilogy of life. Toronto: University of Toronto P, 1996.

- Schwartz, Barth D. Pasolini Requiem. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992.

- Siciliano, Enzo. Pasolini: A Biography. Trans. John Shepley. New York: Random House, 1982.

- Viano, Maurizio. A Certain Realism: Making Use of Pasolini's Film Theory and Practice. Berkeley: University of California P, 1993.

- Willimon, William H. "Faithful to the script", Christian Century (2004).

External links

Who really killed Pier Paolo Pasolini?

A biopic by Abel Ferrara at the Venice biennale will reconstruct the last hours of the Italian film director, who was murdered in 1975

-

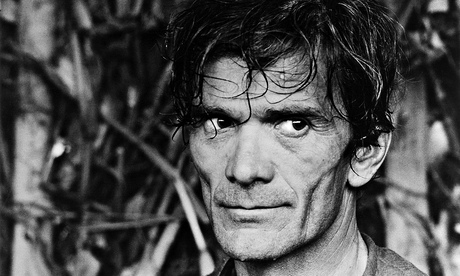

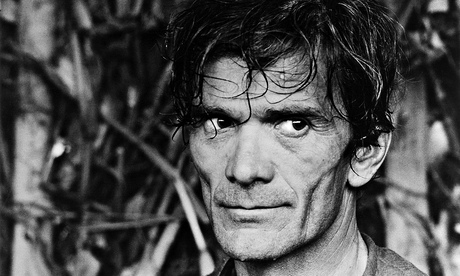

The film of Pier Paolo Pasolini's last day is tipped to win the Golden Lion at the Venice biennale festival Photograph: Allstar Picture Library

"Want to go for a spin?" the poet and maestro of Italian cinema asked the rent boy, according to the latter's confession to the police. "Come ride with me, and I'll give you a present."

So began the events leading to the murder of

Pier Paolo Pasolini, brilliant intellectual, director and homosexual whose political vision – based on a singular entwinement of Eros, Catholicism and Marxism – foresaw Italian history after his death, and the burgeoning of global consumerism. It was a murder that, four decades later, remains shrouded in the kind of mystery and opacity

Italy specialises in –

un giallo, a black thriller.

The encounter occurred in the miasma of hustling around Roma Termini railway station at 10.30pm on 1 November 1975. And it marks the point of departure for a film tipped to win the Golden Lion at the

Venice biennalefestival this week –

Pasolini, starring Willem Dafoe and directed by

Abel Ferrara, Bronx-born of Italian descent. The film deals with the last day of an extraordinary life. Ferrara says: "I know who killed Pasolini," but will not give a name. But in an interview with

Il Fatto Quotidiano, he adds: "Pasolini is my font of inspiration."

At 1.30am, three hours after the station rendezvous, a Carabinieri squad car stopped a speeding Alfa Romeo near the scrappy coastal promenade of Idroscalo at Ostia, near Rome. The driver, Giuseppe (Pino) Pelosi, 17, sought to run, and was arrested for theft of the car, identified as belonging to Pasolini. Two hours later, the director's body was discovered – beaten, bloodied and run over by the car, beside a football pitch. Splinters of bloodied wood lay around.

Pelosi confessed: he and Pasolini had set off, and he had eaten a meal at a restaurant the director knew, the Biondo Tevere near St Paul's basilica, where he was known. Pino ate spaghetti with oil and garlic, Pasolini drank a beer. At 11.30pm they drove towards Ostia, where Pasolini "asked something I did not want" – to sodomise the boy with a wooden stick. Pelosi refused, Pasolini struck; Pelosi ran, picked up two pieces of a table, seized the stick and battered Pasolini to death. As he escaped in the car, he ran over what he thought was a bump in the road. "I killed Pasolini," he told his cellmate, and the police.

Pelosi was convicted in 1976, with "unknown others". Forensic examination by Dr Faustino Durante concluded that "Pasolini was the victim of an attack carried out by more than one person".

On appeal, however, the "others" were written out of the verdict. Pelosi had acted alone and the master was dead in a squalid tryst gone wrong and best forgotten, perhaps even deserved. But fascination with Pasolini and his films (in Italy, his writing too) increased – as did that with mysteries that still hang over his last hours.

The renown of his work is manifestly on merit: New York's

Moma mounted a retrospective in 2012, the

BFI in 2013. In April this year the Vatican, which had once pursued Pasolini and helped secure a criminal conviction for blasphemy, declared his masterpiece,

The Gospel According to St Matthew, "the best film ever made about Jesus Christ". This expression of Pasolini's radical faith portrays Jesus as a revolutionary "red Messiah", according to the Franciscan doctrine of holy poverty, which in part influences the current pontiff, Francis.

But the compulsion of his death is less explicable: in 2010 the former mayor of Rome and leader of the centre-left Democratic party, Walter Veltroni, demanded that the case be reopened on the basis of a convergence of strange, and politically charged, circumstances.

Pasolini was killed the day after his return from Stockholm, where he had met Ingmar Bergman and others in the Swedish cinematic avant-garde, and given an explosive interview to L'Espresso magazine. In it, he addressed his favourite theme: "I consider consumerism to be a worse form of fascism than the classic variety."

Pasolini's view of a new totalitarianism whereby hyper-materialism was destroying the culture of Italy can be seen now as brilliant foresight into what has happened to the world generally in an internet age. But his critique had been, for months before the murder, more specific. He had singled out television as an especially pernicious influence, predicting the rise and power of a type such as media-mogul-turned-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi long before time. More specific still, he had written a series of columns for Corriere della Sera denouncing the leadership of the ruling Christian Democratic party as riddled with Mafia influence, predicting the so-called Tangentopoli – "kickback city" – scandals 15 years later, whereby an entire political class was put under arrest during the early 1990s. In his columns, Pasolini declared that the Christian Democratic leadership should stand trial, not only for corruption but association with neo-fascist terrorism, such as the bombing of trains and a demonstration in Milan.

Again, a spine-chilling vindication: these were the so-called "years of lead" in Italy, culminating in the bombing of Bologna station five years after Pasolini's death by neo-fascists working with the secret services, killing 82 people.

I was a student in turbulent Florence in 1973, returning every year thereafter and affiliated to a radical organisation called Lotta Continua (Struggle Continues); and I well remember Lotta Continua's newspaper taking contributions from Pasolini, though his relationship to the radical movements spawned by 1968 was ambiguous. He had identified with police officers against student rioters because, he said, they were "sons of the poor" attacked by bourgeois "daddy's boys".

So it was that, in the wake of the murder in 1975, those close to Pasolini saw the hand of power behind his killing. It would not have been a first: prominent leftists were often attacked or killed; feminist Franca Rame, who would marry the anarchist playwright Dario Fo, was gang-raped by neo-fascists, urged by the Carabinieri.

Members of Pasolini's family and circle of friends, and the writers Oriana Fallaci and Enzo Siciliano raised possible political motives for the killing and produced evidence that contradicted Pelosi's confession, such as a green sweater found in the car that belonged neither to Pasolini nor Pelosi, and Pasolini's bloody handprint on its roof (there were barely any bloodstains on Pelosi). Motorcycle riders and another car had been seen following the Alfa Romeo.

In January 2001 an article appeared in La Stampa that turned conspiracy theory into a hard lead. It concerned the death in 1962, in a plane crash, of Enrico Mattei, head of the ENI energy giant, made into a famous film by Francesco Rosi, with whom Pasolini had worked.

The article's author, Filippo Ceccarelli – one of Italy's expert political journalists – cited inquiries by a judge, Vincenzo Calia, into political intrigue within ENI, which found the plane had been shot down. Judge Calia implicated the man who succeeded Mattei, Eugenio Cefis, in cahoots with political leaders. The report cited a journalist who had worked on The Mattei Affair film with Rosi, Mauro di Mauro, who was kidnapped and disappeared without trace.

Long before Calia's investigation, published in 2003, Pasolini had worked on the posthumously released book Petrolio, featuring barely disguised versions of Mattei and Cefis, and revealing knowledge of how the ENI scandal and murder went to the heart of power and the P2 Masonic lodge, of which Cefis was a founder member. "With 25 years' foresight," wrote Ceccarelli, "Pasolini the writer had been aware of the outcome of a long investigation."

Then, in 2005, the floodgates opened. Pelosi, interviewed on television, retracted his confession, saying that two brothers and another man had killed Pasolini, calling him a "queer" and "dirty communist" as they beat him to death. They frequented, he said, the Tiburtina branch of the MSI neo-fascist party. Three years later, Pelosi gave further names in an essay called "Deep Black", released by the radical publisher Chiarelettere, revealing connections to even more extreme fascist cells tied to the state secret services, saying he had not previously dared to speak, after threats to his family.

One of Pasolini's closest friends, assistant director Sergio Citti, then came to the fore to say that his own investigations had produced evidence entirely overlooked: bloodied pieces of the stick dumped close to the football pitch, and a witness ignored by the official investigation who had seen five men drag Pasolini from the car.

Citti introduced a new theme: the theft of spools from Pasolini's last film,Salò, the return of which he had tried to negotiate. The gang of thieves frequented, it emerged, the same billiard bar as Pelosi, and had called Pasolini on the last day of his life to organise a meeting. Another investigation by the writer Fulvio Abbate tied the killers to the famous Magliana criminal gang on the coastal outskirts of Rome.

Yet the case remains closed, and there are those within Pasolini's circle as well as in the political class who prefer it so. Author Edoardo Sanguineti calls the death "delegated suicide" by a sado-masochist bent on his own destruction. Pasolini's cousin Nico Naldini – also a homosexual poet – wrote in the ambiguously entitled Brief Life of Pasoliniabout the director's "fetishistic rituals" and "attraction for boys who made him lose his sense of danger".

Pasolini had died, so history insists, as though in a scene from one of his films. "It is only at the point of death," Pasolini had said in 1967, "that our life, to that point ambiguous, undecipherable, suspended – acquires a meaning."