Mosaics made of mirror shards and tiles cover each wall. Glittering chandeliers hang from the ceilings and spots of light dance in the domes.

2017年1月31日 星期二

2017年1月28日 星期六

12 World-Class Museums You Can Visit Online

The digital age has made it possible—easy, even—to visit some of the world’s most famous museums from the comfort of your own home.

From mental_floss

12 World-Class Museums You Can Visit Online

Rudie Obias

filed under: art, internet, Lists, museums

JOEL SAGET/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

While it’s hard to beat the experience of seeing a seminal piece of fine art or important historical artifact with your own two eyes, one could easily spend a lifetime traveling the world in search of all of them. Fortunately, the digital age has made it possible—easy, even—to visit some of the world’s most famous museums from the comfort of your own home. Here are a dozen of them.

1. THE LOUVRE

The Louvre is not only one of the world’s largest art museums, but it’s also one of Paris’ most iconic historic monuments. The museum offers free online tours of some of its most important and popular exhibits, such as its Egyptian Antiquities. You can take a 360-degree look at the museum, and click around the rare artifacts to get additional information on their histories.

2. SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

While the architecture of the Guggenheim’s building itself, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, is quite impressive, you don’t have to visit the Big Apple to get an up-close view of some of the priceless pieces of artwork inside. The museum makes some of its collections and exhibits available online for people and students who want to get a taste of what the museum can offer, including works from Franz Marc, Piet Mondrian, Pablo Picasso, and Jeff Koons.

3. NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART

Founded in 1937, National Gallery of Art is free and open to the general public. For those who aren’t in Washington D.C., it also provides virtual tours of its gallery and exhibits, including “Van Gogh’s Van Goghs: Masterpieces from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam” and "Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia: Millennium of Glory.”

4. BRITISH MUSEUM

With a collection that totals more than eight million objects, London’s British Museum makes some of its pieces viewable online, including "Kanga: Textiles From Africa" and "Objects From The Roman Cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum." The museum also teamed up with the Google Cultural Institute to offer virtual tours using Google Street View technology.

5. SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Washington D.C.’s National Museum of Natural History, one of the most visited museums in the world, offers a peek at its wonderful treasures with an online virtual tour of the entire grounds. Viewers are welcomed into its rotunda and are greeted with a comprehensive room-by-room, 360-degree walking tour of all its exceptional exhibits, including the Hall of Mammals, Insect Zoo, and Dinosaurs and Hall of Paleobiology.

6. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

The Met is home to over two million works of fine art, but you don’t have to be in New York City to enjoy them. The museum’s website features an online collection and virtual tours of some of its most impressive pieces, including works from Vincent van Gogh, Jackson Pollock, and Giotto di Bondone. In addition, The Met also works with the Google Cultural Institute to make even more artwork (that’s not featured in its own online collection) available for view.

7. DALÍ THEATRE-MUSEUM

Located in the town of Figueres in Catalonia, Spain, the Dalí Theatre-Museum is completely dedicated to the artwork of Salvador Dalí. It features many rooms and exhibits surrounding every era of Dalí’s life and career, and the artist himself is buried here. The museum offers virtual tours of the grounds and a few exhibits, such as the surreal display of Mae West's Face.

8. NASA

NASA offers free virtual tours of its Space Center in Houston, with a wise-cracking animated robot named “Audima” as your tour guide.

9. VATICAN MUSEUMS

The Vatican Museums feature an extensive collection of important art and classical sculptures curated by the Popes over many centuries. You can take a virtual tour of the museum grounds and iconic exhibits, including Michelangelo’s ceiling of The Sistine Chapel.

10. NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY MUSEUM

The mission statement of the National Women’s History Museum in Alexandria, Virginia is to educate, inspire, empower, and shape the future “by integrating women’s distinctive history and culture in the United States.” Part of that mission is delivered through well-curated online exhibits, including exhibits surrounding women in World War II and the rights of women throughout American history.

11. NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE

The National Museum of the United States Air Force is the official museum of the United States Air Force and centered on Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. It houses a wide array of military weapons and aircrafts, including the presidential airplanes of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Richard Nixon. The museum also offers free virtual tours of its entire grounds, such as decommissioned aircrafts from World War II, Vietnam, and the Korean War.

12. GOOGLE ART PROJECT

To help its users discover and view important artworks online in high resolution and detail, Google partnered with more than 60 museums and galleries from around the world to archive and document priceless pieces of art and to provide virtual tours of museums using Google Street View technology. The Google Art Project features fine art from the White House, the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, and even São Paulo street art from Brazil. Check out a complete list of museums you can visit online through the Google Art Project and the Google Cultural Institute.

2017年1月24日 星期二

British Museum, most accessible collection of masterpieces

This is London’s most accessible collection of masterpieces – but no one has heard of it. (BBC Culture)

The world-famous British Museum has a secret: a hidden study where anyone may request private viewings of prints and drawings by Rembrandt, Michelangelo and more.

BBC.COM|由 SOPHIE HARDACH 上傳

2017年1月15日 星期日

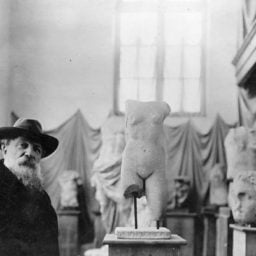

AUGUSTE RODIN By RAINER MARIA RILKE; Standing Female Nude in a Vase (Rodin) These assemblages, “small floral souls that you have raised up out of antique vases” Rilke

AUGUSTE RODIN

By

RAINER MARIA RILKE

Translated by Jessie Lemont and Hans Trausil.http://www.gutenberg.org/files/45605/45605-h/45605-h.htm

[ARTWORK OF THE WEEK] Standing Female Nude in a Vase. These assemblages, “small floral souls that you have raised up out of antique vases”, as Rilke used to say, show how creative and ingenious Rodin was.

Learn more : http://ow.ly/MTDYd

Gauguin’s Ramblings of a Wannabe Painter. Proust’s Chardin and Rembrandt

New Books: Gauguin and Proust Meet at the Border of Painting and Literature

What does it take to bridge the gap between art and prose?

The old quarrel between critics and artists (especially painters) plays out with exuberance in two pamphlet-like essays now available from David Zwirner Books. Adding to their charm, both works were written by unmistakable voices from fin-de-siècle France—Marcel Proust and Paul Gauguin—and both beam with a zeal for the art of painting.

The previously untranslated books—Gauguin’s Ramblings of a Wannabe Painter (trans. Donatien Grau) and Proust’s Chardin and Rembrandt (trans. Jennie Feldman)—are notable for their unabashed Frenchness, but they also deserve attention as minor classics of “ekphrasis,” or the translation of one art form into another; in this case, both writers transcribe their experience of paintings into ecstatic prose. As it happens, too, ekphrasis is the name of the series to which these amusing, memorable books belong.

In his essay on Chardin and Rembrandt, a youthful Proust plays the role of critic: he commits a passionate act of ekphrasis by describing master paintings in long, euphoric paragraphs. He’s particularly smitten with Chardin’s “rich depiction of mediocrity,” his elevation of the everyday and commonplace. It’s a bonus that these sections come across as moody prototypes of passages from his In Search of Lost Time—Swann’s Way was first published almost twenty years later.

Gauguin, for his part, spends most of Ramblingsof a Wannabe Painter offering hilarious one-liners that convey his disdain for “elite” critics, whom he halfheartedly believes make up a nefarious “Literati.” It doesn’t take him long to compare critics to know-nothing typists, even as he denounces the “erudite” “autocracy” they impose. In Gauguin’s mind, the league of critics is more or less a religion of fools. “You could even call it,” he adds, “theocracy of the typewriter.”

Which is to say that neither of these essays is especially calm: Gauguin refers to his own writing as “the exaggerations of a turbulent mind”; Proust, finally pausing for a breath at the end of his essay, wonders if his intensity would scare Chardin.

For all of their differences in perspective, though, both essayists are at ease in the tempestuous borderland between painting and writing. In some respects, too, Gauguin the Painter and Proust the Novelist share deep affinities.

Paul Gauguin, Nature morte aux pommes (1890). Image: Courtesy Sotheby’s.

Despite his good-natured ribbing of the critics of his day, Gauguin is really offering a 19th-century version of Susan Sontag’s “erotics of art”—he believes the “professional” critics, compensating for a lack of feeling, take revenge through order and analysis. (This is why he refers to himself as a “wannabe” or unprofessional painter.) The irony, though, is that Gauguin’s conviction steers him toward an act of criticism. He soon submits a beautiful passage on Renoir, one that Proust would have enjoyed:

In Renoir nothing is in its proper place: don’t look for a line, it doesn’t exist; as if by magic, a pretty patch of color, a caressing light, say enough. A light fuzz shimmers on cheeks, as on a peach, animated by the wind of love whispering its music into waiting ears. One would like to bite the cherry of that mouth—through the laughter a little tooth appears, sharp and white.

And Proust, for all of his exacting intelligence, agrees with Gauguin about the shortcomings of trained perfection. Here he is sounding Gauguin-like while describing Chardin’s The Hard-Working Mother (1740):

The wrist, the hand are no less significant than the rest, and for a viewer who can appreciate it, even a little finger is an excellent exponent of character, playing its role with pleasing accuracy. Only a petty mind, an artist who at most speaks and dresses as such, looks solely for people in whom he recognizes the harmonious proportions of allegorical figures.

For Proust and Gauguin, it isn’t entirely impossible to explain a painting in prose, at least not in its totality, and not through exposition. Both artist agree, for example, that nothing would be more absurd than to describe a painting to its painter. To finesse this point, Proust relies on the absurdity of a near-tasteless metaphor. “It would likewise astonish a woman who has just given birth,” he writes, “to hear a gynecologist describe the physiological process that she, with mysterious strength, has just carried through without knowing its nature.”

A little something extra, these books argue, is required to bridge the gap between painting and prose. You might call it bafflement, indignation, or exuberance. Either way, it’s a surplus of feeling we often find in artists’ writing, from fin-de-siècle France to the present day—at journals like e-flux and Paper Monument. That these unpublished pieces have returned to readers more than a hundred years after their initial publication suggests they retain what the poet Hölderlin called “the saving power.” It’s an argument, I take it, for where we might turn now.

Los Angeles, lovers and light: David Hockney at 80

From cool blue pools in LA to Yorkshire woodland to desert highways, a major Tate retrospective to mark David Hockney’s 80th birthday celebrates his vibrant vision

From cool blue pools in LA to Yorkshire woodland to desert highways, a major Tate retrospective to mark Hockney’s 80th birthday celebrates his vibrant vision

THEGUARDIAN.COM|由 OLIVIA LAING 上傳

2017年1月14日 星期六

The dark side of the Belle Époque (BBC.COM Fisun Güner)

BBC Culture

Art at the turn of the last century was not all sun-kissed Monet gardens.

The dark side of the Belle Époque

It was a time of angst and decadence, expressed through some truly disturbing paintings, writes Fisun Güner.

BBC.COM|由 FISUN GÜNER 上傳

by Fisun Güner

7 December 2016

When we think about art at the end of the 19th Century, who and what comes to mind? Monet and Impressionism, certainly. Toulouse-Lautrec at the Moulin Rouge, perhaps. Post-Impressionism, of course: Cézanne and his heavy-set cardplayers or Mont Sainte-Victoire shimmering on the horizon, magnificent and majestic; Gauguin in his Tahitian paradise; or the last ravishing landscapes of Van Gogh, who died just as the last decade of the century was getting into its stride.

Art at the end of the 19th Century is as far removed from Monet’s sun-dappled garden as you can get

But when we think of the art that’s actually characterised as the art of the fin de siècle, particularly the last decade of that century, the mood changes, and it darkens. We think of the art of anxiety and angst, of drama and febrile tension, of an acute sense of alienation. And it’s all as far removed from Monet’s sun-dappled garden at Giverny as you can get.

James Ensor, seen here in his studio in 1937, made his body of work an index of the unsettling (Credit: www.lukasweb.be - Art in Flanders vzw/DACS 2016)

We might, for instance, think, most famously, of Munch’s Scream, the first version of which the troubled Norwegian artist painted in 1893, or his various depictions of women as vampires, slaking their sexual thirst on unsuspecting men. Or perhaps our thoughts turn to the young and eccentric English illustrator and printmaker Aubrey Beardsley and his darkly erotic, sinuous vixens – exotic femme fatales who could captivate and destroy any man. And as the embodiment of lust and evil, naturally the femme fatale becomes a mascot of the fin de siècle, just as much as the dandy, that ultra-refined aesthete who rises above ordinary moral concerns, becomes its icon.

Or we might even think of an artist who is currently being shown at the Royal Academy in London: the brilliant Belgian painter James Ensor, whose rich palette glows with Rubenesque colours but whose subject matter is dark and satirical: skulls and skeletons and eerie masks, all representing the corruption at the heart of bourgeois society.

Munch’s The Scream is the best known example of Expressionism, a movement that represented external reality as indicative of emotional states (Credit: Edvard Munch/Wikipedia)

Or his fellow Belgian, the lesser known but equally brilliant Léon Spilliaert, whose thin and haunted features stare out forlornly in his self-portraits, presenting himself as a strange, cadaverous figure trapped in gloomy and oppressive interiors – for Spilliaert, too, is at the Royal Academy, where he complements the work of Ensor, his older contemporary who also lived at Ostend.

Or, in fact, we might even return to Gauguin, who in some ways became a figurehead for these disquieting forces at the end of the century. Gauguin’s fascination with religious and mystical subject matter, and for the purely imaginary and fantastical, were synthesised in his paintings with the ordinary, everyday world that surrounded him - just as James Ensor’s work also provided a synthesis of the real and imagined.

What lies beneath

Ensor grew up above a curio shop in the cold, coastal town of Ostend, where his mother sold trinkets, costumes and grotesque carnival masks to tourists. At first Ensor painted in a loosely Impressionist style, but he retained his childhood fascination with these masks and was soon incorporating them into his work. His favourite motif became that of the surging crowd, where ossified faces are leering, threatening masks that overwhelm the whole picture. For Ensor these props seemed to provide the perfect metaphor for the hypocrisies of polite society.

Ensor’s faces are leering, threatening masks that overwhelm the whole picture

In one painting, The Intrigue, 1890, which forms the centrepiece of the Royal Academy exhibition, a group of grotesques with barely human faces congregate in a bizarre wedding group, the aged bride and her ghoulish top-hatted groom grotesquely inverting family and Christian values to be found in the embodiment of the marriage ritual. in one self-portrait, painted a year earlier, we find the young Ensor in an elaborate, plumed hat, making him appear slightly ridiculous. Surrounded by a swarm of terrifying masks, he stares out at us with a stern and frank gaze. Is he accusing us of some unspecified crime against him, or simply imploring us to bear witness to his suffering?

Aubrey Beardsley helped establish the idea of the femme fatale in his ominous black and white lithographs like The Stomach Dance from 1893 (Credit: Aubrey Beardsley/Wikipedia)

In other canvases, Ensor paints himself as either a skeleton or as a tormented Christ-like figure. In his monumental Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (actually painted in 1888), Christ himself is seen entering the city on a donkey, but is barely discernable amid the crushing crowd – the implication being that these self-obsessed and conservative scions of the city would barely notice the messiah arriving amongst them. And it may be a sidelong reference to Ensor’s own overlooked genius. Like Munch, one gets a sense that Ensor suffered from an acute persecution complex, though unlike Munch, Ensor’s work has a darkly comic edge to it. His fraught paintings bristle with humour and are all the more vivid for that.

So why did artists revel in such outward expressions of unease and dislocation? In an era of relative peace and stability and, for the few, economic prosperity (an era named, after the destruction of the Great War, as the Belle Époque or Golden Age and which stretched from the 1870s to the war’s outbreak) the art of fin-de-siècle Europe expressed something contrary to those outward signs of confidence. These were anxieties connected with a sense of society’s spiritual emptiness and its growing materialism. This was a rejection of the idea that progress and reason, ideas which intellectuals had embraced and promoted since the 18th Century as Enlightenment ideals, could sustain the spirit.

It signalled a deeper anxiety: our inability to control our own destinies.

But perhaps, in a way, these were also anxieties exacerbated by the end of any century. It might sound a trivial connection, but in our own age we might think back to the alarm over the Millennium Bug, where people actually imagined planes falling out of the sky due to programs having accommodated only two digits instead of four (computers would think, when the hour struck, they were back in 1900).

Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? is no tropical idyll – it can be read as a panorama of existential ennui (Credit: Paul Gauguin/Wikipedia)

It signalled a deeper anxiety that is perennial: our inability to know and control our own destinies. Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?,the title from an 1897 painting by Gauguin, seemed to capture this quest for that deeper knowledge – and he and many other artists of the time looked for answers not in science but in esoteric spirituality, in mysticism and often the occult.

Darkness and despair

The fin de siècle encompassed the Symbolist and Decadent movements, which were primarily literary movements flourishing first in France but then all over Europe, and which provided a wellspring of ideas for visual artists. As well as Ensor and Spilliaert, one of the most notable artists in Belgium was Fernand Khnopff, who, like Ensor, was a member of the Belgian avant-group group Les XX and whose most striking painting, L’Art (or The Caresses), 1896, depicted a sphinx with a ‘real’ woman’s head and the body of a leopard, her face the picture of ecstasy as she is shown caressing a male figure (Oedipus).

Fernand Khnopff’s L’Art makes explicit the idea that sexual expressiveness is a form of animal impulse (Credit: Fernand Khnopff/Wikipedia)

It’s a compelling and unsettling image, made stranger for the meticulous realism of its technique with the enigmatic fantasy of its subject. Elsewhere were the weird Goya-esque fantasies of Austrian Alfred Kubin, and, in Germany, the beguiling and erotic paintings of Franz Stuck, who co-founded the avant-garde Munich Secession group in 1892. A generation older, we might also think of the sweeter though no less haunting dream-visions of French artist Odilon Redon.

In literature, one of the most influential works of the Symbolist and Decadent movements was Joris-Karl Huysmans’ À Rebours (Against Nature). Published in 1884, its young anti-hero is an eccentric, reclusive aesthete called Jean des Esseintes who loathes bourgeois society and so roundly rejects it. Instead he surrounds himself with nascent Symbolist poetry and art, and lives a life of excessive sensual indulgence.

Huysmans’ themes certainly found an echo among many artists of the period. The French writer Barbey d’Aurvilly’s reponse to his seminal novel of Decadent literature was revealing in its insight: “For a decadent of this calibre to emerge and for a book like Monsieur Huysmans’ to germinate within a human head, we must have become what in fact we are – a race in its last hour.”

2017年1月8日 星期日

Pompidou Centre review – a 70s French radical that’s never gone out of fashion

Guardian US 分享了 1 條連結。

The much-loved Paris landmark was designed in 1977 by two young unknowns – Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano. On the eve of its 40th…

THEGUARDIAN.COM|由 ROWAN MOORE 上傳

2017年1月7日 星期六

Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746–1828) : Goya Exposed with Jake Chapman

Francisco de Goya, "The Marquesa de Pontejos," c. 1786, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.85

Goya’s Disasters of War: The truth about war laid bare

Goya’s unflinching cycle of drawings, The Disasters of War, are the most searing works of art ever to deal with conflict, argues Alastair Sooke.

BBC NEWS · 182 個分享 · 2014年7月17日

Tomorrow at 6:30 p.m., explore the masterful painterly technique of Francisco de Goya, one of Spain's most celebrated artists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, during this free gallery talk:http://met.org/1MGlZnh #MetFridays

Attributed to Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, 1746–1828) | Majas on a Balcony | ca. 1800–1810

National Gallery

Goya's extraordinary painting of the child Manuel Osorio de Zuñiga, with a pet magpie, will be at 'Goya: The Portraits'.

Members visit for free. Book now: http://bit.ly/1j6hit2

The subject is of this painting by Goya is from a comedy by the playwright, Antonio de Zamora. Don Claudio, the main protagonist, has been led to believe that his life depends upon keeping a lamp alight:http://bit.ly/1SnSHNT

Francisco de Goya was born on this day in 1746.

The years between Goya's appointment as first painter to the court of Charles IV and the Napoleonic invasion of 1808 were a time of great activity and financial security for the artist. He painted some of his finest portraits at that time, "Señora Sabasa García" (c. 1806/1811) and several others in the Gallery's collection among them.

See more works by Goya in our collection: http://1.usa.gov/1CAQvLL

Francisco de Goya was born #onthisday in 1746. Here’s a self-portrait from 1799 http://ow.ly/KYdCp

Francisco Goya

Painter

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker regarded both as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns. Wikipedia

Born: March 30, 1746, Fuendetodos, Spain

Died: April 16, 1828, Bordeaux, France

Period: Romanticism

Milos Forman's Goya's Ghosts

The New York Review of Books

A series of nine prints and paintings that show the power and breadth of Francisco Goya’s work, with commentary by Colm Tóibín

Goya: Order and Disorder

http://j.mp/15tTjNv

訂閱:

意見 (Atom)