Art to Make You Laugh (and Cry)

Steve Legato for The New York Times

Fluxspace, an art collective, is housed in a former textile mill. More Photos >

Published: August 27, 2009

Philadelphia

Skip to next paragraph

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

Steve Legato for The New York Times

Two text murals, at far right, created by the Mural Arts Program, which has worked with Philadelphia residents and artists to produce more than 2,800 works. More Photos »

WHEN it rains, geysers of water have been known to erupt from the floor drains of the art collective here known as Fluxspace, which makes its home in a mammoth former textile mill in the northern part of the city. The building has no air-conditioning, and on the harshest winter days its heating system borders on notional. It’s also a bear to find: one morning this week a taxi driver on his way to it ended up taking several unintended detours down trash-filled alleys, cursing the calm voice issuing from his dashboard G.P.S.

But the three-year-old collective is becoming known in the Philadelphia art world for its monthly exhibitions of work by its members and other artists. And “we actually get awesome turnout for our shows, considering the location and everything,” said Danielle Ruttenberg, one of 25 young artists who either pay for raw studio space in the building or take on chores in exchange for it. (The current exhibition, of bird-centric prints and drawings by a local artist named Tory Franklin, continues through Sept. 13.)

I had sought out Fluxspace at the beginning of Day 2 of a thoroughly idiosyncratic personal art tour (with some good eating woven in) of a city that has emerged, especially over the last decade, as a lively and unpredictable place to see new art.

There is a particularly Philadelphian brand of hardy, low-budget, do-it-yourself, do-it-for-love creativeness evident in art and art spaces across the city. It is a climate that, as new as it sometimes feels, has been embodied and nurtured for decades by organizations like two I included on my itinerary: the Fabric Workshop and Museum, founded in 1977 as a way to combine world-class artistic collaborations with community outreach and education, and the Mural Arts Program, which grew out of the city’s anti-graffiti efforts and has worked with neighborhood residents and artists for 25 years to create more than 2,800 towering murals on walls throughout the city.

But my first stop, after stepping off the train in 30th Street Station on Monday morning, was a real outlier: a tiny, hidden museum that interested me not because of new art — most of its pieces are well over a century old — but because of the obsessive nature it shares with so many places in the city, the sense that it exists only because its founders felt a necessity borne of fascination. Located on the grounds of a cemetery in the suburb of Drexel Hill, the Museum of Mourning Art — a name to make Edward Gorey proud — is a compilation of American and European funerary art and artifacts from several private collections, assembled by the family that has owned the cemetery for generations.

The small, haunting, very serious collection includes an ornate horse-drawn hearse from 1890, parked over a coffin made in 1610 with an oval window in the lid so — as the museum’s curator, Elizabeth Wojcik, explained — one could make the sure the deceased was good and deceased, and so the soul had an easy means of egress.

Housed in a reproduction of Mount Vernon, the museum centers on the profusion of objects (broaches, ribbons, books, paintings, embroidery) that were produced in the wake of the prolonged period of mourning after Washington’s death. And its highlight is one of a small number of mourning rings ordered to be made by Washington’s will, with a small glass oval lined with seed pearls and filled with gray strands of the president’s hair. The museum’s visitors — tours are by appointment — run the gamut from historians to artists to student undertakers to those who simply seem to be drawn to things deathly. (I was there that morning with two local artists and jewelry designers interested in mourning jewelry.)

“There’s a woman who comes in a lot,” said Ms. Wojcik, pointing out a gorgeous 1797 memorial embroidery, “and stands in front of this work and looks at the weeping willows in it and just cries and cries.”

As much as I enjoyed a museum about death and decay, I found myself slightly relieved that I had already eaten, at an unassuming nearby diner called the Hibernia Deli Coffee Shop, which serves a superb full Irish breakfast: eggs, beans, black and white pudding, thick rashers, potatoes and even a good grilled tomato.

For the rest of my dining, in the spirit of the trip, I decided to stick exclusively to restaurants in Philadelphia’s unusual bring-your-own-bottle scene, a huge number of no-wine-list establishments that have sprung up partly because of Pennsylvania’s state-controlled alcohol sales system, which means smaller profits and expensive licensing costs for restaurant owners. Many of the B.Y.O.B. restaurants are tiny, run by chefs who, maybe because of the absence of a bar, put the focus intensely on the food, which can be fantastic.

For lunch I visited Matyson — a longtime favorite among local foodies, opened in 2003 near Rittenhouse Square — and had perfectly cooked scallops on a bed of succotash, a Pennsylvania Dutch staple, with big, plump lima beans. (I forgot to hunt down a wine store ahead of time and had to settle for iced tea.)

Nicely fed, I walked over to the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, a 47-year-old center for the work of self-taught artists which has also, since 1997, focused on contemporary artists whose work reflects the influence of such outsider art. The show on view, “Frenz,” which ends on Saturday, is a good, oddball one, with pieces by 11 artists who were chosen by the indie musician Will Oldham, including hilarious, rustic drawings by Able Brown, a New York City park ranger, and powerfully strange collages by Mr. Oldham’s mother, Joanne. A surreal, as yet unfinished animated video work by Lori Damiano, an artist in Portland, Ore., composed of thousands of her individual drawings, is almost impossible to take your eyes off of.

Next I made my way to the Fabric Workshop and Museum, the nonprofit art space founded by Marion Boulton Stroud that has finally — maybe — secured a permanent home in the eight-story building near the Philadelphia Convention Center that it moved into last year after inhabiting several other homes in the course of its 32 years. Over that time the workshop’s definition of fabric (wicker, horsehair, paper, wood, film emulsion, even metal) has grown almost as expansive as its list of artists in residence who have come to make works there: Vito Acconci, Claes Oldenburg, Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois, Roy Lichtenstein and Rachel Whiteread, to name just a few.

The workshop’s current show includes work by four artists living in Philadelphia — Tristin Lowe, Virgil Marti, Peter Rose and Ryan Trecartin — and is worth the trip if only to spend some time walking around Mr. Lowe’s “Mocha Dick,” a life-size re-creation, in pale industrial felt, of the notorious 19th-century sperm whale of that name that inspired Melville’s great white menace. This version, which took Mr. Lowe and a team from the workshop six months to make, is inflated and dominates a huge eighth-floor gallery, a ghostly beached immensity encrusted with sewn barnacles and scored with realistic-looking harpoon scars and squid-tentacle circles.

After seeing such a big fish, it was somehow appropriate — and also convenient for a writer later to be in need of a good transition — that I went to dinner that night at a wonderful South Philadelphia restaurant called Little Fish, which has room inside for about 20 people, if you don’t count the cooks crammed into the narrow open kitchen. The restaurant’s much-praised chef, Mike Stollenwerk, wasn’t there — he is busy getting ready to open a bigger sister restaurant, to be called Fish.

But Chadd Jenkins, the sous chef, filled in beautifully, with an appetizer of sweet peekytoe crab arranged atop a tarragon-infused fried green beefsteak tomato and an unlikely but delicious jerk-style lobster dish (inspired by Mr. Jenkins’s recent vacation to Jamaica) over a rice-and-peas risotto with nice black-eyed peas instead of kidney beans.

My second day started with a strong cup of cappuccino from Old City Coffee, a Philadelphia roaster, in the Reading Terminal Market, and then the long, wandering ride with the cursing cabby to Fluxspace. Amy Adams, the director of the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, had suggested the day before that if I were in the area, I should also check in on one of the stranger collectives to spring up recently in the city, the impressively named Philadelphia Institute for Advanced Study, whose Web site, pifas.net, presents it as a gleaming-glass academic palace rising above manicured grounds.

It is actually located in an old, ramshackle industrial space that its founders — Brandon Joyce and Richard Davis, who met while studying philosophy at the University of Virginia — discovered after they lost a previous space as a result of what Mr. Joyce called a “profound misunderstanding” with their landlord, which led to a police raid. (“I think he thought we were running some sort of a criminal enterprise in there,” Mr. Joyce said.)

Pifas, as the collective is known, is like Fluxspace in some ways, a fluid gathering of artists paying ridiculously low rent for studios in a city that is unlike New York, as Mr. Joyce observes, in that “there are gobs of space — it’s like you can just walk down the street and grab it.” But the institute often functions more like a friendly anarchist academy, with lectures and seminars and experiments, than a place for making and showing art. (The next event open to the public, on Saturday at 8 p.m., is described as “an intrepid show of audio, poetry and acrobatics” by the institute’s scholar in residence, Luke Yates, a doctoral student from the University of Manchester in England, about Henry Box Brown, a slave who mailed himself in a box to Philadelphia in 1849.)

Lunch with Mr. Joyce was a quick but decadent suckling-pig hoagie from a tiny storefront called Paesano’s, an offshoot of another highly regarded Italian B.Y.O.B. called Modo Mio, just across West Girard Avenue from the sandwich shop.

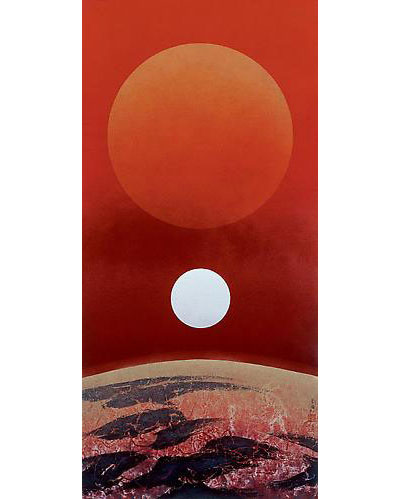

The final stop on my tour actually ended up being many stops, as I stared out the window of an elevated-subway train in West Philadelphia, where the Mural Arts Program has been working for weeks with the artist Stephen Powers, a West Philadelphia native, and many local painters to create a series of more than 30 huge, text-based murals, collectively called “Love Letter,” along a sometimes blighted stretch of Market Street.

The project, painted in consultation with business and building owners, is in part Mr. Powers’s homage to Darryl McCray, known as Cornbread, a legendary Philadelphia graffiti artist who began painting messages of love on walls in the late 1960s to impress his girlfriend. (Mr. McCray also once managed to tag the Jackson Five’s private jet, and painted “Cornbread Lives” on the side of an elephant at the Philadelphia Zoo to dispel rumors that he had died.)

Jane Golden, the executive director of the Mural Arts Program, said she remembered Mr. Powers as a teenager, when he was a prolific and notorious graffiti writer known as Espo who couldn’t be persuaded to “come over to the other side” and paint legally. So there is a “wonderful irony,” she said, to the fact that now, as an established gallery artist living in New York, he has returned to Philadelphia to mount an ambitious urban beautification project, one whose odd, affectionate messages — like “Forever Starts When You Say Yes” and “Pre-pay is on/Let’s talk/Till my minutes are gone” — are about love and reconciliation. (The project will be unveiled officially on Sept. 10, though most of the signs are now visible for the price of a $2 subway token.)

Mr. Powers said the idea was to create a single, serial urban work whose hopeful messages might resonate with a kind of universality in a neighborhood in need of hopeful messages. And as a fringe benefit, he said the murals might even help in a more practical way.

“Hopefully, there will be a few sly guys out there who say to their girl: ‘Hey, Baby, I wrote that up there for you.’ ”

New York Public Library Sketches that were drawn by New York Public Library staff members in the process of designing a new lion logo.

New York Public Library Sketches that were drawn by New York Public Library staff members in the process of designing a new lion logo. New York Public Library The old logo of the New York Public Library would lose detail when it was too small.

New York Public Library The old logo of the New York Public Library would lose detail when it was too small. New York Public Library The library’s new lion logo.

New York Public Library The library’s new lion logo.