Bringing Art and Change to Bronx

Thomas Hirschhorn Picks Bronx Development as Art Site

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

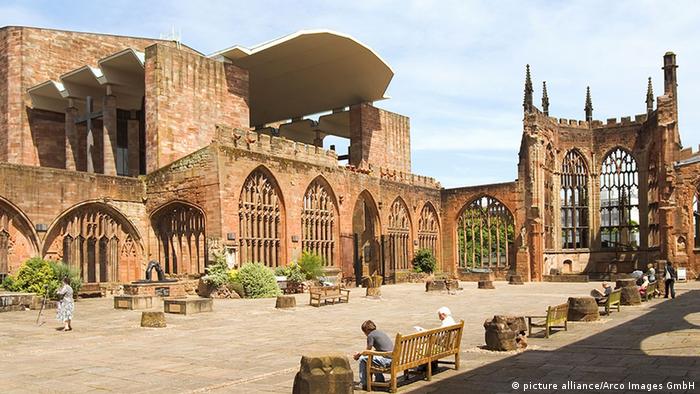

The temporary Gramsci Monument, under construction at the Forest Houses development in the South Bronx. More Photos »

By RANDY KENNEDY

Published: June 27, 2013

Last year a tall man in a dark suit with thick black-frame glasses —

something like a combination of Morrissey and Samuel Beckett — began

showing up at housing projects all over New York City. He attended

residents’ meetings and spoke rapturously in a heavy Germanic accent

about an improbable dream: finding people to help him build a monument

to the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who died in Rome in

1937.

Multimedia

“Believe it or not, people have come to us with stranger ideas before,”

said Erik Farmer, the president of the residents’ association at Forest

Houses project in the Morrisania section of the South Bronx.

Neither Mr. Farmer nor many of the people who attended these meetings had ever heard of the man, Thomas Hirschhorn,

a 56-year-old Swiss artist with a huge international following. But Mr.

Hirschhorn wasn’t interested in trading on his reputation.

“Some people think I am a priest or an eccentric rich man, and some

people just think I’m a loser,” he said late last year in an interview,

as he was making his visits. “But that is O.K. as long as they

understand that I am serious.”

For the last two decades, few contemporary artists have been serious in

quite the same way as Mr. Hirschhorn. His deeply political work —

usually made with cheap materials assembled to look like totems of a

postapocalyptic garbage cult — has long forced art lovers to face some

very uncomfortable issues: oppression, poverty, abuse of power, the

atrocities of war, and a culture of easy pleasure that makes it easy to

ignore all those things.

On Monday, with the help of the Dia Art Foundation and Mr. Farmer, Mr.

Hirschhorn will realize his vision of honoring Gramsci, unveiling a

monument on the grounds of Forest Houses. It will exist in a parallel

universe from the rest of the city’s big-money summer exhibitions,

daring viewers to veer far off the beaten museum-and-gallery path and

question their ideas about the value and purpose of art.

Handmade from plywood, plexiglass and miles of beige packing tape — one of Mr. Hirschhorn’s signature art supplies — the Gramsci Monument

bears no resemblance whatsoever to the cenotaphs and glowering statues

that dot the rest of New York. And it doesn’t look much like an artwork,

either. It looks more, in fact, like an adult treehouse or a makeshift

beach cabana or a chunk of set hijacked from the Kevin Costner film “Waterworld.”

Though it might serve to memorialize Mr. Hirschhorn’s tenacity as much,

if not more, than the philosopher it is named for, the monument

epitomizes the broadly humanistic worldview of Gramsci, who spent most

of his adult life in prison under Mussolini and envisioned a

working-class revolution that would begin as much in culture as in

political power.

Throughout the summer, the monument will function as a kind of village

festival, or inner-city intellectual Woodstock, with lectures, concerts,

recitals and art programs on the stages and pavilions that Mr.

Hirschhorn and a paid crew of workers chosen from the Forest Houses have

built over the last several weeks.

The project is the first that Mr. Hirschhorn has built in the United

States and will be the fourth and final such work in a series he began

many years ago dedicated to his favorite philosophers, following a

monument dedicated to Spinoza in Amsterdam in 1999, one to Gilles

Deleuze in Avignon, France, in 2000 and a third to Georges Bataille

in Kassel, Germany, in 2002. From the beginning, the monuments have

been planned and constructed in housing projects occupied mostly by the

poor and working class, with their agreement and help. Mr. Hirschhorn’s

motivations in choosing the sites, however, are never straightforwardly

benevolent.

“I tell them, ‘This is not to serve your community, per se, but it is to

serve art, and my reasons for wanting to do these things are purely

personal artistic reasons,’” Mr. Hirschhorn said. “My goal or my dream

is not so much about changing the situation of the people who help me,

but about showing the power of art to make people think about issues

they otherwise wouldn’t have thought about.”

These days, as the commercial art world feels increasingly like a branch

of high finance, Mr. Hirschhorn is the rare artist who seems to move in

and out of it with a nondenominational fluidity. He is represented by

the prestigious Gladstone Gallery, and his work regularly shows up at

important international art fairs, where it sometimes functions as the

obnoxious party guest. But he has long spoken about the importance of

seeking a “nonexclusive audience” for art. Such an audience includes

those who go to museums and galleries, he says, though they are only a

small part of the potential public for art.

And so when he began flying to New York from his home in Paris last year

to plan the Gramsci monument, he came carrying an obsessively annotated

New York City Housing Authority map; he eventually visited 46 of the

334 projects on that map, trying to find residents who would embrace his

idea.

“I decided — O.K., almost for political reasons — that I wasn’t going to

do it in Manhattan,” he said. “It has to be outside the center.”

After narrowing down the possibilities to seven projects in the Bronx,

he chose Forest Houses — a cluster of high-rise buildings completed in

1956, housing 3,376 people — largely because of the enthusiasm of Mr.

Farmer, 43, who has lived there almost his entire life and functions as

the nerve center for the development. In constant motion around its

grounds in a motorized wheelchair (he lost the use of his legs in a car

accident when he was in college), Mr. Farmer seems to know everyone who

lives in its buildings and to command, if not authority, at least

respect.

He was one of the only people to ask Mr. Hirschhorn for Gramsci’s writings

while considering the monument proposal. And when he and Clyde

Thompson, the complex’s director of community affairs, embraced the

idea, Mr. Hirschhorn said, he felt that he had found partners — in the

cosmology of his art work, he calls them “key figures” — who would be

able to help him see the monument through.

Mr. Farmer said he decided to make a persuasive case for Forest Houses

not only because the monument would provide temporary construction and

security jobs for residents, but because he hoped that it could mean

more for the development.

“There’s nothing cultural here at all,” he said one afternoon in early

June as he watched Mr. Hirschhorn and several residents hard at work on

the monument’s plywood foundation. “It’s like we’re in a box here, in

this neighborhood. We need to get out and find out some things about the

world. This is kind of like the world coming to us for a little while.”

(At the project’s end, the monument will not be packed up and

reconstituted as an artwork to sell or show elsewhere; the materials

will be given to Forest Houses residents in a lottery.)

Over the last two months, I spent several days watching Mr. Hirschhorn

as he plotted out the monument in consultation with Mr. Farmer, whose

job, among others, was to hire residents as temporary employees of the

Dia Art Foundation, which is financing the project. (Those helping to

build and staff the monument are being paid $12 an hour; the state’s

minimum wage is currently $7.25 an hour.)

It was not the first time I had visited the project. As a city reporter for The New York Times, I spent several days at Forest Houses in 1993

when it was roiled by violence in the aftermath of the city’s crack

epidemic, and I accompanied a team of police officers on what was called

a “vertical patrol” of several buildings. The officers, walking with

their guns drawn, would ride the elevators to buildings’ roofs, then

walk down the stairs, fanning out on every floor in a show of force.

Forest Houses is a different place today, with a dramatically lower

crime rate, but violence is still a fact of life. One day as Mr.

Hirschhorn and the workers took a break during the heat of the

afternoon, a young man sprinted by, followed by others shouting that he

had robbed a man in one of the project’s buildings. Two of the men

chasing the accused thief caught him near a plywood walkway for the

monument, tackled him and punched and kicked him for several minutes

until his face was bloodied. He staggered away, to shouted threats.

Mr. Hirschhorn looked on in grim silence, and as soon as the incident

was over he grabbed a sheet of plywood and immediately went back to

work. Mr. Farmer, watching from his wheelchair, shrugged.

“I’m sorry you had to see that, but it’s self-policing, and that’s how

that should work,” he said. “That guy doesn’t live here. He’s not going

to come back here and try to rob anybody anymore.”

Once the monument begins its programming on Monday, it will be open free

to the public seven days a week through Sept. 15, with lectures from

scholars like the philosophers Simon Critchley and Marcus Steinweg; a

daily newspaper published by residents; a radio station; and food

provided by residents chosen by Mr. Farmer.

Whether summer tourists and other art patrons will drive up or walk the

few blocks from the Prospect Avenue subway stop (on the Nos. 2 and 5

lines) is very much an open question. “We all hope that many people find

their way there,” said Philippe Vergne, the director of the Dia Art

Foundation, which took on the project as its first public-art commission

in more than 15 years. “Thomas proceeds from the belief that art really

can change something, and not just a living room.”

At Forest Houses, Mr. Hirschhorn pursues that belief with a messianic

fervor, his wiry, energetic frame seeming to be everywhere at once —

working, sweating, recruiting, philosophizing. And you get the distinct

feeling that visitors are less important to him than the participation

and acceptance of Forest Houses residents, many of whom have progressed

from suspicious bemusement to grudging recognition to near-wholesale

emotional ownership of the project, even older residents who initially

complained that it looked like a shanty rising in their yard.

“You work on something like this, and after a while it’s not like a

job,” said Dannion Jordan, 42, who is helping build the monument. “You

start thinking it’s your thing, too. I mean, I’m no artist, but I’m

making a work of art here.”

As in any ambitious creative endeavor, tensions have sometimes flared.

One day Mr. Hirschhorn pushed the workers to keep at it in a steady

rain, and they balked. “And somebody said to Thomas, ‘You just care

about your work; you don’t love us,’ ” said Yasmil Raymond, Dia’s

curator, who will spend the summer at the monument, as will Mr.

Hirschhorn, who is living in a nearby apartment with his wife and

toddler son.

“Thomas said: ‘It’s true. I do care very much about my work, but I care

about you, too. I am not the boss, and you are not my employees. I am

the artist, and you are helping me,’ ” Ms. Raymond recalled. “Things

kind of gelled after that.”

Mr. Farmer said a reason the tide turned was that Mr. Hirschhorn “works harder than anyone else out here.”

“For him this is a work of art,” he added. “For me, it’s a man-made

community center. And if it changes something here, even slightly, well,

you know, that’s going in the right direction.”

Mr. Vergne added, “People ask what will remain after the monument comes

down in three months, and I think what will remain will be a certain way

to think of the world — if only an urban legend of a Swiss artist who

came from Paris to tell New Yorkers about a dead Italian philosopher,

and people came to hear, and maybe they learned something that matters.”

The Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn is building a

monument to the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci in the

Morrisania section of the South Bronx. Gramsci died in Rome in 1937.

The temporary monument, on the grounds of the

Forest Houses project, is made from plywood, plexiglass and miles of

beige packing tape — one of Mr. Hirschhorn’s signature art supplies. The

project is the first that Mr. Hirschhorn has built in the United

States.

Mr. Hirschhorn, at the Forest Houses construction site.

Randy Kennedy writes: “For the last two decades, few contemporary artists have been serious in quite the same way as Mr. Hirschhorn. His deeply political work — usually made with cheap materials assembled to look like totems of a postapocalyptic garbage cult — has long forced art lovers to face some very uncomfortable issues: oppression, poverty, abuse of power, the atrocities of war, and a culture of easy pleasure that makes it easy to ignore all those things.”

Randy Kennedy writes: “For the last two decades, few contemporary artists have been serious in quite the same way as Mr. Hirschhorn. His deeply political work — usually made with cheap materials assembled to look like totems of a postapocalyptic garbage cult — has long forced art lovers to face some very uncomfortable issues: oppression, poverty, abuse of power, the atrocities of war, and a culture of easy pleasure that makes it easy to ignore all those things.”

A flow chart designed to explain to visitors the nexus of the project.

"Throughout the summer, the monument will

function as a kind of village festival, or inner-city intellectual

Woodstock, with lectures, concerts, recitals and art programs on the

stages and pavilions that Mr. Hirschhorn and a paid crew of workers

chosen from the Forest Houses have built over the last several weeks.”

Some older residents initially complained that it looked like a shanty rising in their yard.

Once the monument begins its programming on July

1, it will be open free to the public seven days a week through Sept.

15, with lectures from scholars like the philosophers Simon Critchley

and Marcus Steinweg.

Biography of Antonio Gramsci by Frank Rosengarten,

taken from the website of the International Gramsci Society

See also:

Antonio Gramsci was born on January 22, 1891 in Ales in the province of Cagliari

in Sardinia. He was the fourth of seven children born to Francesco Gramsci and Giuseppina

Marcias. His relationship with his father was never very close, but he had a strong

affection and love for his mother, whose resilience, gift for story-

In 1897, Antonio’s father was suspended and subsequently arrested and imprisoned

for five years for alleged administrative abuses. Shortly thereafter, Giuseppina

and her children moved to Ghilarza, where Antonio attended elementary school. Sometime

during these years of trial and near poverty, he fell from the arms of a servant,

to which his family attributed his hunched back and stunted growth: he was an inch

or two short of five feet in height.

At the age of eleven, after completing elementary school, Antonio worked for two

years in the tax office in Ghilarza, in order to help his financially strapped family.

Because of the five-

Antonio continued his education, first in Santu Lussurgiu, about ten miles from Ghilarza,

then, after graduating from secondary school, at the Dettori Lyceum in Cagliari,

where he shared a room with his brother Gennaro, and where he came into contact for

the first time with organized sectors of the working class and with radical and socialist

politics. But these were also years of privation, during which Antonio was partially

dependent on his father for financial support, which came only rarely. In his letters

to his family, he accused his father repeatedly of unpardonable procrastination and

neglect. His health deteriorated, and some of the nervous symptoms that were to plague

him at a later time were already in evidence.

1911 was an important year in young Gramsci’s life. After graduating from the Cagliari

lyceum, he applied for and won a scholarship to the University of Turin, an award

reserved for needy students from the provinces of the former Kingdom of Sardinia.

Among the other young people to compete for this scholarship was Palmiro Togliatti,

future general secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and, with Gramsci and

several others, among the most capable leaders of that embattled Party. Antonio enrolled

in the Faculty of Letters. At the University he met Angelo Tasca and several of the

other men with whom he was to share struggles first in the Italian Socialist Party

(PSI) and then, after the split that took place in January 1921, in the PCI.

At the University, despite years of terrible suffering due to inadequate diet, unheated

flats, and constant nervous exhaustion, Antonio took a variety of courses, mainly

in the humanities but also in the social sciences and in linguistics, to which he

was sufficiently attracted to contemplate academic specialization in that subject.

Several of his professors, notably Matteo Bartoli, a linguist, and Umberto Cosmo,

a Dante scholar, became personal friends.

In 1915, despite great promise as an academic scholar, Gramsci became an active member

of the PSI, and began a journalistic career that made him among the most feared critical

voices in Italy at that time. His column in the Turin edition of Avanti!, and his

theatre reviews were widely read and influential. He regularly spoke at workers’

study-

The outbreak of the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 further stirred his revolutionary

ardor, and for the remainder of the war and in the years thereafter Gramsci identified

himself closely, although not entirely uncritically, with the methods and aims of

the Russian revolutionary leadership and with the cause of socialist transformation

throughout the advanced capitalist world.

In the spring of 1919, Gramsci, together with Angelo Tasca, Umberto Terracini and

Togliatti, founded L'Ordine Nuovo: Rassegna Settimanale di Cultura Socialista (The

New Order: A Weekly Review of Socialist Culture), which became an influential periodical

(on a weekly and later on a bi-

For the next few years, Gramsci devoted most of his time to the development of the

factory council movement, and to militant journalism, which led in January 1921 to

his siding with the Communist minority within the PSI at the Party’s Livorno Congress.

He became a member of the PCI’s central committee, but did not play a leading role

until several years later. He was among the most prescient representatives of the

Italian Left at the inception of the fascist movement, and on several occasions predicted

that unless unified action were taken against the rise of Mussolini’s movement, Italian

democracy and Italian socialism would both suffer a disastrous defeat.

The years 1921 to 1926, years “of iron and fire” as he called them, were eventful

and productive. They were marked in particular by the year and a half he lived in

Moscow as an Italian delegate to the Communist International (May 1922-

On the evening of November 8, 1926, Gramsci was arrested in Rome and, in accordance

with a series of “Exceptional Laws” enacted by the fascist-

Yet as everyone familiar with the trajectory of Gramsci’s life knows, these prison

years were also rich with intellectual achievement, as recorded in the Notebooks

he kept in his various cells that eventually saw the light after World War II, and

as recorded also in the extraordinary letters he wrote from prison to friends and

especially to family members, the most important of whom was not his wife Julka but

rather a sister-

After being sentenced on June 4, 1928, with other Italian Communist leaders, to 20

years, 4 months and 5 days in prison, Gramsci was consigned to a prison in Turi,

in the province of Bari, which turned out to be his longest place of detention (June

1928 -

Gramsci’s intellectual work in prison did not emerge in the light of day until several

years after World War II, when the PC began publishing scattered sections of the

Notebooks and some of the approximately 500 letters he wrote from prison. By the

1950s, and then with increasing frequency and intensity, his prison writings attracted

interest and critical commentary in a host of countries, not only in the West but

in the so-

Antonio Gramsci was born on January 22, 1891 in Ales in the province of Cagliari

in Sardinia. He was the fourth of seven children born to Francesco Gramsci and Giuseppina

Marcias. His relationship with his father was never very close, but he had a strong

affection and love for his mother, whose resilience, gift for story-

In 1897, Antonio’s father was suspended and subsequently arrested and imprisoned

for five years for alleged administrative abuses. Shortly thereafter, Giuseppina

and her children moved to Ghilarza, where Antonio attended elementary school. Sometime

during these years of trial and near poverty, he fell from the arms of a servant,

to which his family attributed his hunched back and stunted growth: he was an inch

or two short of five feet in height.

At the age of eleven, after completing elementary school, Antonio worked for two

years in the tax office in Ghilarza, in order to help his financially strapped family.

Because of the five-

Antonio continued his education, first in Santu Lussurgiu, about ten miles from Ghilarza,

then, after graduating from secondary school, at the Dettori Lyceum in Cagliari,

where he shared a room with his brother Gennaro, and where he came into contact for

the first time with organized sectors of the working class and with radical and socialist

politics. But these were also years of privation, during which Antonio was partially

dependent on his father for financial support, which came only rarely. In his letters

to his family, he accused his father repeatedly of unpardonable procrastination and

neglect. His health deteriorated, and some of the nervous symptoms that were to plague

him at a later time were already in evidence.

1911 was an important year in young Gramsci’s life. After graduating from the Cagliari

lyceum, he applied for and won a scholarship to the University of Turin, an award

reserved for needy students from the provinces of the former Kingdom of Sardinia.

Among the other young people to compete for this scholarship was Palmiro Togliatti,

future general secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and, with Gramsci and

several others, among the most capable leaders of that embattled Party. Antonio enrolled

in the Faculty of Letters. At the University he met Angelo Tasca and several of the

other men with whom he was to share struggles first in the Italian Socialist Party

(PSI) and then, after the split that took place in January 1921, in the PCI.

At the University, despite years of terrible suffering due to inadequate diet, unheated

flats, and constant nervous exhaustion, Antonio took a variety of courses, mainly

in the humanities but also in the social sciences and in linguistics, to which he

was sufficiently attracted to contemplate academic specialization in that subject.

Several of his professors, notably Matteo Bartoli, a linguist, and Umberto Cosmo,

a Dante scholar, became personal friends.

In 1915, despite great promise as an academic scholar, Gramsci became an active member

of the PSI, and began a journalistic career that made him among the most feared critical

voices in Italy at that time. His column in the Turin edition of Avanti!, and his

theatre reviews were widely read and influential. He regularly spoke at workers’

study-

The outbreak of the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 further stirred his revolutionary

ardor, and for the remainder of the war and in the years thereafter Gramsci identified

himself closely, although not entirely uncritically, with the methods and aims of

the Russian revolutionary leadership and with the cause of socialist transformation

throughout the advanced capitalist world.

In the spring of 1919, Gramsci, together with Angelo Tasca, Umberto Terracini and

Togliatti, founded L'Ordine Nuovo: Rassegna Settimanale di Cultura Socialista (The

New Order: A Weekly Review of Socialist Culture), which became an influential periodical

(on a weekly and later on a bi-

For the next few years, Gramsci devoted most of his time to the development of the

factory council movement, and to militant journalism, which led in January 1921 to

his siding with the Communist minority within the PSI at the Party’s Livorno Congress.

He became a member of the PCI’s central committee, but did not play a leading role

until several years later. He was among the most prescient representatives of the

Italian Left at the inception of the fascist movement, and on several occasions predicted

that unless unified action were taken against the rise of Mussolini’s movement, Italian

democracy and Italian socialism would both suffer a disastrous defeat.

The years 1921 to 1926, years “of iron and fire” as he called them, were eventful

and productive. They were marked in particular by the year and a half he lived in

Moscow as an Italian delegate to the Communist International (May 1922-

On the evening of November 8, 1926, Gramsci was arrested in Rome and, in accordance

with a series of “Exceptional Laws” enacted by the fascist-

Yet as everyone familiar with the trajectory of Gramsci’s life knows, these prison

years were also rich with intellectual achievement, as recorded in the Notebooks

he kept in his various cells that eventually saw the light after World War II, and

as recorded also in the extraordinary letters he wrote from prison to friends and

especially to family members, the most important of whom was not his wife Julka but

rather a sister-

After being sentenced on June 4, 1928, with other Italian Communist leaders, to 20

years, 4 months and 5 days in prison, Gramsci was consigned to a prison in Turi,

in the province of Bari, which turned out to be his longest place of detention (June

1928 -

Gramsci’s intellectual work in prison did not emerge in the light of day until several

years after World War II, when the PC began publishing scattered sections of the

Notebooks and some of the approximately 500 letters he wrote from prison. By the

1950s, and then with increasing frequency and intensity, his prison writings attracted

interest and critical commentary in a host of countries, not only in the West but

in the so-

___

黒板消しでパソコンをきれいに!?

黒板消しでパソコンをきれいに!?