Pompidou Centre: A radical with enduring appeal

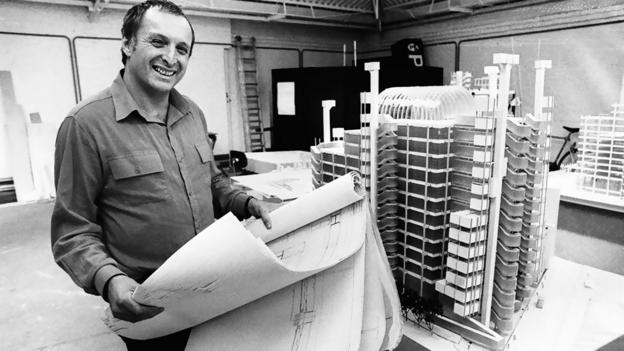

HIDE CAPTION

- Competition time

- In 1969, Richard Rogers, a young British architect, was persuaded to enter a competition to design the Pompidou Centre by his friends Renzo Piano and Ted Happold. (Photo: Corbis)

The Pompidou Centre was panned by the critics when it opened in 1977.

But its colourful exuberance has ensured its lasting popular appeal,

writes Jonathan Glancey.

“The

funny thing looking back is that, to begin with, I hadn’t been at all

keen on the project”, says Richard Rogers of the Parisian building that

made him world famous. The Pompidou Centre – a still shocking, if much

admired hi-tech cultural centre in the heart of Paris – was, at the time

an international competition was held for its design in 1969, a symbol

of everything the 36-year-old left-wing architect stood against.

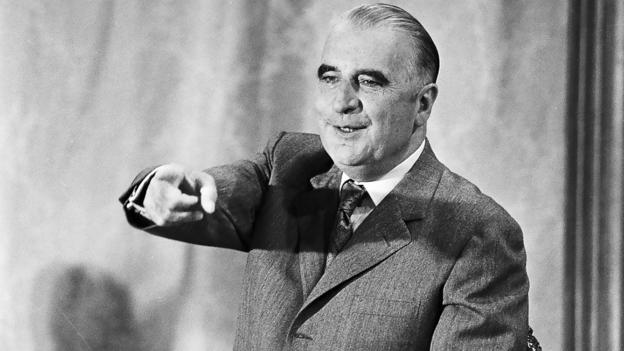

What was known then as the Centre Beaubourg was to be a state monument, a centralised museum proposed by a new, right-wing French president, Georges Pompidou, the very man who, as prime minister under President de Gaulle, had put a end to the student demonstrations and riots of the previous year. Many in France believed these to be the opening shots in a new French Revolution that would bring down General de Gaulle, his government and the state itself, together with proposals for costly national monuments.

After much intellectual arm-wrestling, Rogers was persuaded by colleagues and associates – principally Ted Happold, a structural engineer, and Renzo Piano, a lively Genoese architect raised in a family of builders – to have a shot at the Parisian competition.

Even then, the team of young long-haired, tie-dyed architects and engineers nearly missed the last post with their package of drawings, one of 681 entries in the competition. A month later, Rogers’ phone rang. It was Piano. “Vecchio” he said, (Piano has always called Rogers, who is four years older, “old man”), “are you sitting down? We’ve won the Pompidou . . .”

It was hard to believe. The Piano and Rogers’ design looked like no other museum or cultural centre. With exposed and brightly coloured ductwork and escalators climbing, zigzag style in transparent tubes across its challenging façade, the building was planned as “a cross between the British Museum and Times Square.” It was as hip a design for a public building as could be imagined, a cultural centre for the iconoclastic new worlds of Pierre Boulez in music, Andy Warhol in art and Jean-Luc Godard on screen.

Are friends electric?

The first sight of the design team did little to sway establishment fears in France that they had been landed with the architectural equivalent of Electric Ladyland by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture”, says Rogers. “When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was “Ça va faire crier” [This is going to make a noise]; but, we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success.”

President Pompidou had been remarkably gracious to these young radicals. As for popularity, the cultural centre that now bears his name entertained six million visitors in its first year – making it more popular than the Eiffel Tower.

Because it was so avant-garde a design, it was a challenge to build, especially so when the budget was cut in half. Rogers and Piano relied heavily on the ingenuity of Peter Rice, a brilliant young Irish structural engineer, who had only recently solved the problem of how to build the wild, sail-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House.

Beam me up

“Peter transformed the competition entry for Pompidou from a design that was in some ways too mechanistic into one that was humanistic”, says Rogers. “He softened the whole look of the building through the way he reconfigured the structure. There’s a lot of handcraft in the building, too, which might surprise a lot of people, and that’s one of Peter’s great contributions. The cast steel ‘gerberettes’ – or special beams – that allowed us to have a deep, free floor space by carrying the weight of the floors to the outside of the building brought light and grace to the final structure; they were fettled by hand.”

Rice was thrilled when he came across an old Parisian lady stroking the cast steel beams of the building – telling him how lovely the texture was. “Before working with Peter, we existed in a world of I-beams and the kind of conventional steelwork that would have made the walls of Pompidou look heavy; we were looking for transparency, the idea of a cultural centre that was truly open to everyone with nothing to hide from the public” he said

The Pompidou Centre opened in 1977. By and large, critics panned it. It was an “oil refinery” of a building, shocking, provocative and insensitive to the city streets around it. And, yet, it has become one of the key buildings of the second half of the 20thCentury, and hugely popular for its location, events and the enduring appeal of its extrovert and adaptable design, a colourful climbing-frame of a building extending an open invitation to all ages and generations.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

What was known then as the Centre Beaubourg was to be a state monument, a centralised museum proposed by a new, right-wing French president, Georges Pompidou, the very man who, as prime minister under President de Gaulle, had put a end to the student demonstrations and riots of the previous year. Many in France believed these to be the opening shots in a new French Revolution that would bring down General de Gaulle, his government and the state itself, together with proposals for costly national monuments.

After much intellectual arm-wrestling, Rogers was persuaded by colleagues and associates – principally Ted Happold, a structural engineer, and Renzo Piano, a lively Genoese architect raised in a family of builders – to have a shot at the Parisian competition.

Even then, the team of young long-haired, tie-dyed architects and engineers nearly missed the last post with their package of drawings, one of 681 entries in the competition. A month later, Rogers’ phone rang. It was Piano. “Vecchio” he said, (Piano has always called Rogers, who is four years older, “old man”), “are you sitting down? We’ve won the Pompidou . . .”

It was hard to believe. The Piano and Rogers’ design looked like no other museum or cultural centre. With exposed and brightly coloured ductwork and escalators climbing, zigzag style in transparent tubes across its challenging façade, the building was planned as “a cross between the British Museum and Times Square.” It was as hip a design for a public building as could be imagined, a cultural centre for the iconoclastic new worlds of Pierre Boulez in music, Andy Warhol in art and Jean-Luc Godard on screen.

Are friends electric?

The first sight of the design team did little to sway establishment fears in France that they had been landed with the architectural equivalent of Electric Ladyland by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture”, says Rogers. “When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was “Ça va faire crier” [This is going to make a noise]; but, we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success.”

President Pompidou had been remarkably gracious to these young radicals. As for popularity, the cultural centre that now bears his name entertained six million visitors in its first year – making it more popular than the Eiffel Tower.

Because it was so avant-garde a design, it was a challenge to build, especially so when the budget was cut in half. Rogers and Piano relied heavily on the ingenuity of Peter Rice, a brilliant young Irish structural engineer, who had only recently solved the problem of how to build the wild, sail-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House.

Beam me up

“Peter transformed the competition entry for Pompidou from a design that was in some ways too mechanistic into one that was humanistic”, says Rogers. “He softened the whole look of the building through the way he reconfigured the structure. There’s a lot of handcraft in the building, too, which might surprise a lot of people, and that’s one of Peter’s great contributions. The cast steel ‘gerberettes’ – or special beams – that allowed us to have a deep, free floor space by carrying the weight of the floors to the outside of the building brought light and grace to the final structure; they were fettled by hand.”

Rice was thrilled when he came across an old Parisian lady stroking the cast steel beams of the building – telling him how lovely the texture was. “Before working with Peter, we existed in a world of I-beams and the kind of conventional steelwork that would have made the walls of Pompidou look heavy; we were looking for transparency, the idea of a cultural centre that was truly open to everyone with nothing to hide from the public” he said

The Pompidou Centre opened in 1977. By and large, critics panned it. It was an “oil refinery” of a building, shocking, provocative and insensitive to the city streets around it. And, yet, it has become one of the key buildings of the second half of the 20thCentury, and hugely popular for its location, events and the enduring appeal of its extrovert and adaptable design, a colourful climbing-frame of a building extending an open invitation to all ages and generations.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.