こっか〔コククワ Kokka〕【国華】 月刊美術雑誌。明治22年(1889)岡倉天心・高橋健三らが創刊。東洋美術、特に日本美術の作品紹介と研究論文を掲載。

Kanō Tan'yū (狩野 探幽, 4 March 1602 - 4 November 1674) was one of the foremost Japanese painters of the Kanō school. His original given name was Morinobu; he was the eldest son of Kanō Takanobu and grandson of Kanō Eitoku. Many of the most famous and widely known Kanō works today are by Tan'yū.

Kano Tanyu's sketches: focusing on birds, animals and figures

2011/04/28

This is a part of the Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons Screen.

This is a part of the Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons Screen.

Editor's Note: The following articles are translations of reviews carried by the latest issue ( No. 1386) of Kokka, a prestigious art magazine published in Japan. The publication, which specializes in old Japanese and Oriental art, was founded in 1889 by Tenshin Okakura, a well-known Japanese art critic and philosopher (1862-1913), among others. It is held in high esteem by researchers and experts aboard.

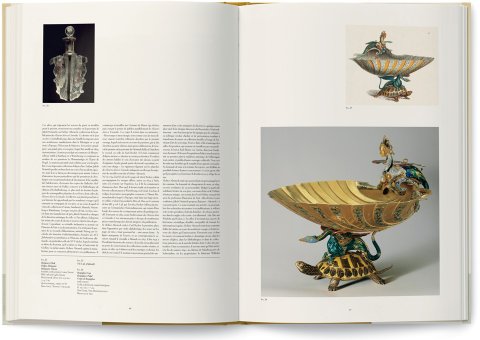

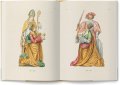

Plate 1 (color) Swan

by Kano Tanyu

Hanging scroll, color on paper

H. 56.5cm, W. 130.0cm

Hatakeyama Memorial Museum, Tokyo

By Hiroko Kato

What are we to be made of the sketches by Kano Tanyu (1602-1674)?

Tanyu's sketches and finished paintings have up to now been handled separately. Though Tanyu is heralded as a pioneer in sketching from life, because of the importance of his rank as a painter in service to the shogunate, he was criticized for not being able to display his pre-modern sensibilities in public or use his sketches in his main works. However, a clarifying full study based on the art work as to the reasons for the differences in the works has yet to be conducted.

Regardless of the fact that in the Edo period the terms shasei and shashin were used interchangeably, they have in the past been discussed separately based on genre differences between animal paintings and people portraits. This article discusses them together. Bird and flower paintings, for example, could be called "portraits of birds and animals," and it can be noted that he made shashin life-size sketches of birds and animals, with notations about the depictions (form and color information) on the works to indicate the individual features of each model. Thus, even in cases where corresponding sketches are not extant today, he did create finished works on the basis of related sketches and thus transferred important painting data from the sketch to the finished work.

In terms of the shashin of human figures that were created as sketches for portraits, judging from the records of the production process, it can be said that unlike present-day sketches Tanyu made "sketches from memory" after having fully observed his subject. Even if he did create works based on direct sketches, as indicated by the term shashin, the final goal was shin or idealized truth. This applies not only to human portraits, but also to animal paintings which are "portraits of bird and animals." Therefore we can argue that by necessity this led to a difference between the motifs in sketches and finished paintings. Further, in portraits the sitter's social rank and virtue were symbolized by costume and accompanying items, while with images of birds and animals in paintings importance is conveyed by the depiction of the fur or feathers covering the subject's body. The subject is separated visually by the emphasis on color and pattern rather than form. We can discern the underlying worldview of the artist from this tendency of vision and depiction to discern and depict difference. This is a world view that sees a union of subject and object, that confirms that all living beings are the manifestation of God's design, one that differs greatly from the post-Renaissance naturalism and the objective view established by the realism of the 19th century. If that is the case, then naturally there are divisions between the sketching form nature established in the Renaissance drawing study and the application of methods that collate the motifs in the finished picture.

The shin or truth that was Tanyu's goal was based on traditional forms and depictive methods, and on grasping immediately that which was not readily apparent, bringing in new reproductive depiction with iconographic information that was based on a subtle balance between those traditional factors and life sketching. If we recognize that the gap between sketches and finished bird and flower paintings seen in Tanyu, Ogata Korin and Watanabe Shiko was quite considerable by the time we reach Maruyama Okyo, then we can interpret this not as a reflection of the artist's social standing, but rather the change in the shin sought by the artist in each period. In the future, should we re-evaluate an artist or an art work based on whether or not a sketch motif was directly linked to a finished work and the degree to which it was reflected in that work, or rather should we clarify the change in the nature of the shin sought by the period and the artist?

The author is an art historian (Japanese painting) and research assistant at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts.

* * *

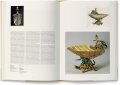

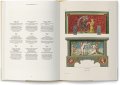

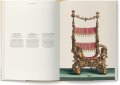

Plates 2 and 3 (color)

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons Screens

by Ito Jakuchu

Pair of six-panel screens, ink on paper

Four paintings on outer edges:

Each H. 134.8cm, W. 48.4cm

Other eight paintings:

Each H. 134.8cm, W. 51.1cm

By Hideyuki Okada

The mid-Edo period Kyoto-based painter Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) painted this pair of six-panel screens with attached paintings. Working from the right end of the right screen, the paintings depict plum blossoms, peonies and butterflies, rooster and bamboos, bird and pine tree, mynah bird and willow tree, bird and lilies. Working from the right of the left screen, the images are chrysanthemums, tororo-aoi hibiscus, hawk and oak tree, bird and banana plant, Mandarin duck and reeds, and narcissus. Thus, these paintings clearly present from right to left a seasonal progression of spring, summer, autumn and winter birds and flowers.

These twelve paintings each have two different seals impressed upon them, for a total of 24 different seals. Of those, newly recognized seals on the works can be seen in the "To-Keiwa-shi" seal on the 5th panel of the right screen (5th painting), "Azana-iwaku-Keiwa" seal (7th painting), "To-shi-Keiwa" (10th painting) and "Nitto-To-Jokin (11th painting). The first panel on the right screen and the 6th panel on the left screen are inscribed with the date "Horeki 9" (1759), and thus we know that Jakuchu painted these works during the spring of his 44th year. That extremely productive year also saw the creation of five hanging scrolls from the Colorful Realm of Living Beings series and fifty fusuma sliding door panels for the Main Shoin of Rokuonji (Kinkakuji). This painting with its known production date is particularly important in the consideration of the development of Jakuchu's ink painting style.

The author is an art historian (Japanese painting) and curator of MIHO MUSEUM.

* * *

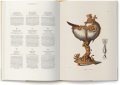

Plate 4 (color) Seated Image of Shoku

Wood

Fig. H. 88.6cm

Founders Hall, Engyoji, Hyogo Prefecture

By Yoshiteru Kawase

This wooden sculpture is said to be the image of Priest Shoku (1007). Shoku was a Tendai priest of the mid-Heian period, traditionally said to have founded Engyoji on Mt. Shosha in Hyogo prefecture in 966. This seated image is slightly bigger than life-size with a figure height of 88.6cm, with a head that is sharply pointed in the back. The eyes are downcast and the protruding eyebrows combine with the hands tucked into his sleeves in front of his waist to form a unique figural form.

According to production records, a fire occurred in the temple's Founders Memorial Hall in the 8th month of 1286, and this reduced the image created after Shoku's death to ashes. In 1288 the temple commissioned the Buddhist sculptor Keikai to created a new image based on a painted portrait. A glass jar containing Shoku's ashes had been found in the old sculpture, and records show that this same jar was placed inside the new sculpture.

This work was carved from kaya wood (torreya nucifera) and its style is generally faithful in an exaggerated expression, with naturally expressed drapery. Recent study of the image included an X-ray examination which revealed a globe-shaped, glass vessel, thought to contain bones and ash, inside the head, confirming the record about the transfer of the Shoku's remains.

In recent years, a portrait sculpture of a priest was discovered at the temple, greatly damaged overall but luckily with the carved surface of the head, torso and back area remaining in good condition. The carving and style appear to be from the end of the 10th century through the beginning of the 11th century, suggesting that this work dates almost back to the days of Shoku himself. It is possible that this figure was the very image damaged in the 1286 fire.

The author is an art historian (Japanese sculpture) and an investigator of the Fine Arts Division in the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

* * *

Research Material

The Self-Portrait of Matsudaira Sadanobu

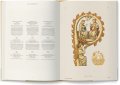

Plate 5 (color)

Self-Portrait of Matsudaira Sadanobu

Hanging scroll, color on silk

H. 108.0cm, W. 110.0cm

Chinkokushukoku Shrine, Mie Prefecture

By Yasunao Kawanobe

Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759-1829) was a chief shogunal councilor and clan lord of the Shirakawa clan during the late Edo period. Born in Horeki 8・1758), he was the son of Tayasu Munetake, from one of the three Tokugawa families, and a descendant of the 8th Tokugawa shogun Yoshimune.

Today there are several images of Matsudaira Sadanobu known. The most famous example is the portrait in the Chinkokushukoku Shrine in Kuwana, Mie Prefecture, which is a self-portrait painted when he was 30 years of age. This image is said to have been used as a substitute for Sadanobu when he was absent from the Shirakawa clan lands.

In addition to this image there are several other images known which depict Sadanobu after his retirement and assumption of the artistic name Rakuo. The work in the collection of the Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art is particularly well known. That image is also said to be a self-portrait. Another painting that closely resembles the Fukushima Museum image is today in Shogenji in Kuwana. The Shogenji work is stored in a box whose lid interior is inscribed in ink with the story of how the work was created. According to this box inscription, there was a self-portrait by Sadanobu of his own features, to which the oku-eshi painter to the shogunal family Kano Osanobu (1796-1846) jadded the body and garment sections. The portraits of Matsudaira Sadanobu are particularly fascinating materials in our understanding of the relationship between pre-modern clan lord portraits, self-portraiture and the work of shogunal oku-eshi painters.

The author is an art historian (Japanese painting) and curator of Fukushima Prefectural Museum

* * *

Translated by Martha J. McClintock