*慕尼黑發現上千納粹掠奪藝術品

在慕尼黑市發現1500幅被納粹盜竊的藝術作品,其中包括畢加索,馬蒂斯和夏加爾的繪畫作品。誰是這些作品的合法主人,目前完全不清楚。

在成堆的空罐頭盒和紙箱中間,堆放著這些價值連城的繪畫藝術品。現在的問題是,首先要通過司法途徑澄清所有權問題。對於所有人來說,1500幅被納粹掠奪的這些藝術品的被發現都是令人震驚的大事。發現如此規模的被掠奪藝術品,這在德國戰後歷史上還是第一次。

令人難以置信的藝術寶藏

據新聞雜誌《焦點》週刊報導,海關人員在兩年前就對科內柳斯·古利特(Rolf Nikolaus Cornelius

Gurlitt)的住宅進行了清查。2010年9月海關人員在對一列火車的旅客進行例行檢查時,古利特引起了稽查人員的注意。之後,當局在其住宅內發現了這些令人瞠目結舌的藝術寶藏:從畢加索到馬蒂斯,從夏加爾到貝克曼以及藝術史上其他大師的傑作。

古利特收藏這些繪畫顯然已經有幾十年。它們都是其父親,1956年去世的著名藝術經銷商希爾德布蘭·古利特Hildebrand Gurlitt)的藏品。在20和30年代,希爾德布蘭·古利特曾擔任茨維考博物館館長和漢堡藝術協會主席。他被視為是推動現代藝術的先驅。自從納粹開始系統地沒收被他們稱為「墮落」的藝術品之後,古利特也失去了他的工作。

但古利特後來順應了新的局勢,開始與納粹當權者配合。他與其他三家藝術品經銷商一起管理被納粹掌控的藝術品交易。1937年,他們在慕尼黑推出了一個臭名昭著的「被沒收藝術品」展覽。由於展品不符合納粹意識形態,被稱為「墮落」的藝術品。因此納粹委託古利特將這些藝術品出售,尤其是銷往國外。

在德國一家研究所任職的哈爾特曼博士(Dr. Uwe Hartmann)認為,其中一些作品可能被這幾位藝術品經銷商自己買了下來。估計所發現的1500幅作品中,也有納粹自1933年以來在國內外掠奪的一些藝術品。例如希特勒和戈林就曾大規模收集他們所喜歡的,主要是著名大師的作品。這批巨大收藏有哪些人的作品,目前只有幾位專家知道。2年來對慕尼黑藝術藏品進行研究的藝術史學家霍夫曼是其中之一。

拍賣行的作用備受爭議

專家們也在問,慕尼黑的藝術珍寶2011年就被發現,為什麼持續了這麼長的時間公眾才知道這件事情?專家科爾德豪夫說:「迄今誰也沒有說,在這住宅內發現的全都是當年德國博物館內的收藏。」他的意思是,其中可能有許多猶太人的私人收藏。如果是這樣的話,「可能有很多繼承人,其中包括一些多年來不惜支付昂貴律師費,尋找遺失藝術品的猶太人後代,也希望早些知道有些藝術品無需再找了,因為已經在慕尼黑被發現。」

在對這些收藏的處理上,拍賣行的作用也備受爭議。從法律角度上來說,人們無法要求拍賣行在收購、或繼續出售來歷不明的藝術品時,要遵守現行法律。除了司法程序外,拍賣行還面臨一個道德問題:「從道德上來說,古利特當然屬於迫害和沒收財產政策的受益者,不管是直接或間接,即便是其後代也必須面對這一歷史。」如何處置這批納粹時期收藏延續至今的財產,必須進行認真的思考。(節錄自德國之聲中文網2013/11/5報導)

納粹藏畫重新浮現,藝術超越時代

藝術MICHAEL KIMMELMAN2013年11月06日

在昏暗的燈光下,自畫像中的奧托·迪克斯(Otto Dix)咬着牙,目露慍色。抽着雪茄的他看上去怒氣衝天。依舊年輕的他彷彿是在問:「為什麼用了這麼久?」

這些當年落入納粹手裡的藝術品正在源源不斷地浮現,就像被衝上岸的瓶子一樣。三年前,一台前端式裝載機在柏林為一座新地鐵站進行挖掘作業時,

發現了少量隱藏在那裡的雕塑作品。

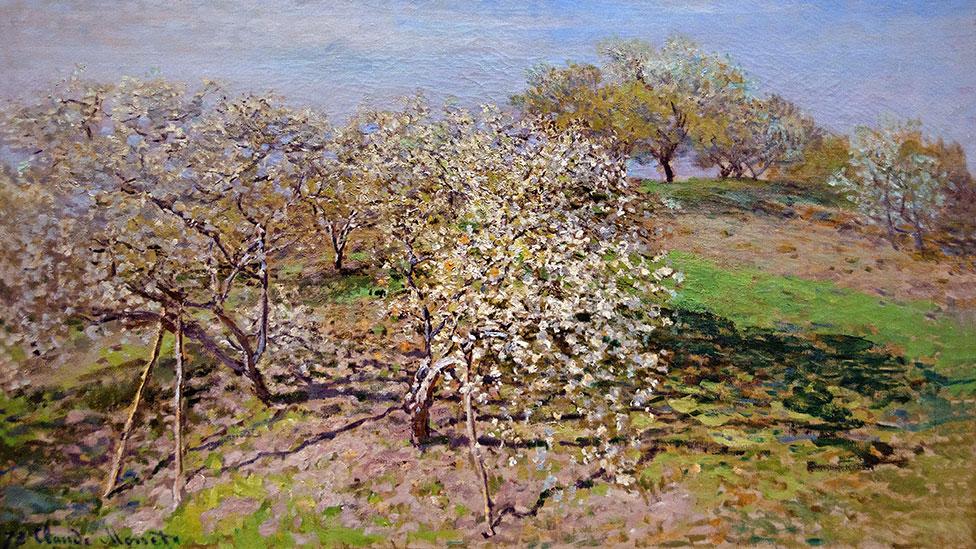

現在又出現了約1500幅畫作,這批寶藏的價值難以估量。其中部分作品在周二德國奧格斯堡舉行的新聞發佈會上得到展示。從網上最早幾幅

模糊的翻拍圖片來

看,新發現的畫作似乎包括了馬蒂斯(Matisse)、庫爾貝(Courbet)、弗朗茲·馬爾克(Franz Marc)、馬克斯·利伯曼(Max

Liebermann)、馬克·夏加爾(Marc Chagall)、馬克斯·貝克曼(Max

Beckmann)和恩斯特·路德維格·基希納(Ernst Ludwig

Kirchner)的作品。這些畫是在一個名叫廓尼琉斯·古爾利特(Cornelius

Gurlitt)的老年男子位於慕尼黑的公寓里發現的。古爾利特的父親希爾德布蘭特(Hildebrand)是納粹時期的一名畫商,收集了一批被希特拉

(Hitler)認為「墮落」的現代派藝術作品。

納粹最重要的目標之一就是:凈化德國的博物館,洗劫私人藏品。但有

違常理的是,他們囤積了自己厭惡的現代派藝術作品,為了換取硬通貨,還要將部分作品賣到國外去。希爾德布蘭特正是約瑟夫·戈培爾(Joseph

Goebbels)為這一任務挑選的畫商之一。他們將部分藝術品展出是為了加以批判,但展覽後來卻引起了轟動,激怒了元首。在那之後,成千上萬件被沒收的

作品就不見了蹤影。

但隨着時間的流逝,不願被遺忘的那些藝術品,又陸續被人們發現。

左起順時針,奧托·迪克斯的一幅自畫像;馬克斯·利伯曼的一幅油畫和馬蒂斯的一幅女人的畫像。

迪克斯也以倔強的姿態回歸了。迪克斯為希特拉所不容,不僅是因為他

的畫尖銳、粗糲、令人毛骨悚然,描繪了一戰帶來的破壞,展現了魏瑪共和國的焦慮,還因為他的作品嘲諷了德國對英勇的定義。在慕尼黑髮現的這幅自畫像是迪克

斯1919年創作的,從這幅畫中傳遞出的一種驕傲來看,迪克斯似乎已經準備好戰鬥,去打敗一個當時尚未露面的敵人。而最後,他和他的作品,生命都比那個敵

人更長。

慕尼黑髮現的這些作品是從納粹製造的廢墟中搶救出來的,像這樣的發

現,尤其令人動容的不僅是它們經歷了多年風雨得以保存,也不僅是因為它們之中可能有失落的傑作,儘管偶爾的確會有。甚至不是因為它們象徵著數百萬逝去的生

命,而是因為它們戰勝了希特拉在另一個場合曾提及的「大謊言」。希特拉當時說,假話假到「一定程度」,人們就會情不自禁地相信。

這裡的大謊言指的是現代藝術的墮落。這個謊言意在摧毀、消滅藝術世界。儘管各種繪畫作品和雕塑作品很脆弱,這一點令人遺憾,但它們代表的那些最美好的理想卻並不脆弱。因此,馬蒂斯筆下那個膝上放着一把扇子、頸上戴着珍珠項鏈、戴着頭巾的女子就證明了藝術不屈不撓的理想。

這幅畫似乎出自20世紀20年代,當時馬蒂斯住在尼斯,人稱「里維

埃拉的蘇丹」(Sultan of the

Riviera)。但它卻是永恆的。經過圖案的堆疊,平淡無奇的立體派變成了繁複濃密的肖像畫,畫面以看似寧靜的家居環境和主人公的性姿態為主題。那位女

子不苟言笑,襯着面孔的是她方形的衣領,手指拘謹地握在一起,她的線條柔和卻暗藏不安,就彷彿是在等待一個秘密情人。馬蒂斯在尼斯的創作一度被人認為是他

的敗筆,不過是裝飾畫。但現在則不同。這幅肖像畫證明了畫家的優勢所在,以及他對藝術之美的恆久貢獻。

現在又出現了約1500幅畫作,其中包括馬克·夏加爾的作品。

這些作品引發的第一輪輿論狂潮還在繼續,在所有的媒體不可避免地將

注意力轉向價格和來源之前,我們還是可以來感嘆命運的力量,它甚至能戰勝人類最邪惡的野心。誰能知道,這些畫作得以保存下來究竟是出於貪婪、恐懼,還是對

它們的熱愛。最終,真正重要的只有:它們倖存下來了。藝術家們在創作時往往徒勞地希望作品的價值能超越時間,這是對後人下的賭注;而對希特拉憎惡的許多藝

術家而言,藝術創作是為了阻止希特拉掌握最終發言權的一種直接努力。在華沙猶太區生活的猶太人,將成千上萬份文件藏在牛奶罐里埋在地下,也是為了同一個目

的。那些牛奶罐的發現為我們提供了大量的歷史文獻,記錄了那些不知所蹤的人留下的故事。

德國小說家W·G·澤巴爾德(

W. G. Sebald)

在《異鄉人》(The

Emigrants)中,回憶起一個被人遺忘的阿爾卑斯山登山者時寫道,「這樣一來,那些死去的人們,就能不斷回到我們的生活中。」在那名登山者失蹤了幾

十年之後,他的遺骨突然暴露在冰川之上。居斯塔夫·庫爾貝(Gustave Courbet)的《鄉村女孩與山羊》(Village Girl With

a

Goat)如今也從荒野回歸,它並不是在納粹時期消失的,而是在1949年一場拍賣會之後,成為了古爾利特的收藏。從畫面來看,這位鄉村女孩是庫爾貝作品

中常見的主人公:粗曠、性感、豐滿、臃腫,有着粉紅色的臉頰,她心不在焉地抱着一隻正在嗅聞的山羊,抓着它的腿,她的眼光望向畫外某處我們看不到的地方。

或許是一名主顧,又或許是一個記號。

《風景與馬》(Landscape With Horses)也再度出現,這是

弗朗茲·馬爾克的

一幅作品。納粹們沒收了一些這樣的作品,儘管馬爾克得到過「鐵十字勳章」(Iron

Cross),並已在一戰中英勇戰死。他1914年寫信給畫家瓦西里·康定斯基(Wassily

Kandinsky),說他相信這場戰爭將會「凈化歐洲」。但第三帝國(Third

Reich)的男人們還是覺得,馬爾克的抽象風格超出了他們可接受的範圍。這幅風景畫不僅超越了他自己的妄想,也躲過了希特拉發起的運動。

居斯塔夫·庫爾貝的《鄉村女孩與山羊》是1500幅最近在慕尼黑被發現的畫作中的一幅。

Christof Stache/Agence France-Presse Ã

同樣地,人們還找到了

基希納的《憂鬱的女孩》(Melancholy Girls)。這幅畫描繪了一個飽經摧殘的裸體女子,她的臉上布滿了疤痕似的線條,彷彿樺樹的樹皮。基希納是他那個時代的又一個犧牲品。納粹對現代藝術的攻擊令他崩潰,他在親手毀掉自己的許多作品後,自殺了。

更大的真相即將顯露。

翻譯:陳亦亭、曹莉

In a Rediscovered Trove of Art, a Triumph Over the Nazis’ Will

By MICHAEL KIMMELMANNovember 06, 2013

Otto Dix, in a half-light, glowers from a

self-portrait, jaw set, puffing on a cigar, looking infuriated. “What

took so long?” he seems to ask, youthful as ever.

They keep coming back, these works of art lost to the Nazis, like bottles washed ashore. Three years ago, a small stash of

sculptures turned up when a front-loader was digging a new subway station in Berlin.

Now some 1,500 pictures, an

almost unfathomable trove, have surfaced; some were revealed in a news

conference on Tuesday in Augsburg, Germany. From the

first few blurry online reproductions

they seem to include paintings by Matisse and Courbet, Franz Marc and

Max Liebermann, Marc Chagall, Max Beckmann and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner,

discovered in the Munich apartment of an old man named Cornelius Gurlitt

whose father, Hildebrand, a dealer during the Nazi era, assembled a

collection of the Modernist art that Hitler called “degenerate.”

Among the very first goals of

the Nazis was to purge German museums and ransack private collections.

Perversely, they stockpiled the modern art they hated, some to sell

abroad in exchange for hard currency. Hildebrand was one of the dealers

whom Joseph Goebbels picked for this task. Some art they paraded in an

exhibition of shame. The show ended up a blockbuster, infuriating the

Führer. After that, thousands upon thousands of confiscated works

disappeared.

But as the years have gone by, art continues to be found, refusing oblivion.

Dix

has returned, defiantly. He was despised by Hitler not just because he

drew and painted in a spiky, gnarled, ghoulish way that decried the

ravages of World War I and spoke to Weimar anxiety, but because his art

mocked the German idea of heroism. The Munich self-portrait conveys a

pride that seems ready to vanquish an enemy that had not quite appeared

on the scene when Dix painted the work in 1919 but that both he and his

art would outlast.

What’s especially moving about

finds like the one in Munich, salvaged from the Nazi ruins, is not just

that they survived all these years or that they might include lost

masterpieces, although they rarely do. It is not even that they

represent tokens of lost lives, millions of them. It is that they

overcame what Hitler in another context once referred to as “the big

lie,” an untruth “so colossal,” he said, that people could not help

falling for it.

The big lie in this case

involved the depravity of modern art. The lie was meant to turn death

and destruction onto the world of art. But while paintings, drawings and

sculptures are sadly fragile, the ideals they represent — the best

ones, anyway — aren’t. And so the painted woman by Matisse, fan in lap, a

string of pearls around her neck, a veil draped over her hair, is a

testament to art’s indefatigable ambitions.

The work looks to be from the

1920s, when Matisse lived in Nice as the Sultan of the Riviera. But it’s

timeless. Pattern on pattern, the picture nestles benign Cubism into a

luxuriant portrait of deceptive domestic tranquillity and sexual poise.

The woman, stern face framed by a square collar, fingers nervously

knitted, is all soft curves and implicit apprehension, as if awaiting

some secret lover. Once upon a time, Matisse’s Nice pictures were

dismissed as decorative fluff. Not now. The portrait speaks to the

strength of its maker and his enduring contribution to the catalog of

beauty.

During this first frantic flush of publicity,

before all the news inevitably turns to price tags and provenance, it’s

still possible to appreciate the whims of fortune, which can trump even

humanity’s most demonic ambitions. Who knows whether these pictures were

preserved out of greed or fear or love? What matters in the long run is

only that they made it. Artists tend to produce art as a vain bulwark

against time, a gamble on posterity; and for many of the artists whom

Hitler loathed, art was an explicit attempt to prevent him from getting

the last word. Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto stored thousands of documents

in buried milk cans for that same reason, and the discovery of those

cans has provided history with the great archive of a lost people.

“And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” as the German novelist

W. G. Sebald

wrote in “The Emigrants,” recalling a forgotten Alpine climber, whose

remains a glacier suddenly gave up many decades after he had

disappeared. Gustave Courbet’s “Village Girl With a Goat” is back from

the wilderness now, having dropped off the map not during the Nazi era

but sometime after an auction in 1949, ending up among the Gurlitt

horde. She’s by all appearances a familiar Courbet heroine, insolent and

voluptuous, fleshy, puffy and pink-cheeked, clutching the legs of the

sniffing goat she absently cradles, her gaze turned to something out of

the picture we can’t see.

A client, perhaps, or maybe a mark.

“Landscape With Horses” has resurfaced, too. The Nazis confiscated works like this one by

Franz Marc

despite the fact that he had earned an Iron Cross and died a hero

during World War I. He wrote to the painter Wassily Kandinsky in 1914

that he believed the war would “purify Europe.” The Third Reich’s men

still found Marc’s abstract style beyond the pale. This landscape

survives his own delusions as well as Hitler’s campaign.

And so, too, does “Melancholy Girls” by

Kirchner,

an image of a naked, ravaged woman whose face is scarred by lines like

the bark of a birch tree. Kirchner was another casualty of his era. So

devastated by the Nazis’ attack on modern art, he destroyed many of his

own works. Then he took his own life.

The bigger truth will out.

誰保護了那些納粹劫掠的藝術瑰寶?

藝術PATRICIA COHEN2013年11月07日

在第二次世界大戰進入尾聲的那段時期,一群盟軍士兵、藝術史專家、

博物館策展人和學者們,殫精竭慮地保護着歐洲的文化遺產,追回被納粹及其同謀劫掠的數百萬件藝術品和其他珍寶。這個綽號「古迹衛士」(Monuments

Men)的團體為珍寶設立了一系列的臨時收藏點。他們看管的藝術品中包括115幅油畫、19幅素描和6箱物品,英國人於1945年在漢堡發現了這些珍寶。

馬克·馬蘇洛夫斯基(Marc Masurovsky)本周在美國國家檔案館(National Archives)位於馬里蘭州學院園(College

Park)的分館發現的文件顯示,這些作品的登記物主是希爾德布蘭特·古爾利特(Hildebrand

Gurlitt),馬蘇洛夫斯基是大屠殺藝術追索計劃(Holocaust Art Restitution Project)的創始人。

而今,在六十多年後,追索專家們表示,這些曾託付給「古迹衛士」的

藏品,有可能是1400多幅令人驚嘆的藏匿品的一部分。2012年,德國調查人員從古爾利特之子廓尼琉斯·古爾利特(Cornelius

Gurlitt)的公寓里沒收了這些作品,並在本周公開了這些作品。這被認為是二戰結束以來所發現的,規模最大的一批失蹤歐洲藝術品。

有五年時間,老古爾利特堅稱這些作品理應歸他所有。納粹指定了一些畫商向國外銷售從猶太人和博物館沒收來的藝術品,從而換取外匯,老古爾利特就是其中的一個。隨着歐洲的追索努力最終漸漸停止,威斯巴登一家收藏中心的管理人員同意把這些藝術品還給古爾利特。

1950年12月15日,當時盟軍行動的領導者,美國人西奧多·海

因里希(Theodore

Heinrich)簽署了文件,把珍寶交給了古爾利特。在交還給希爾德布蘭特·古爾利特的珍寶中,有幾幅畫的名字及描述,與藏在他兒子雜亂無章的公寓里的

那些畫相吻合,其中包括奧托·迪克斯(Otto Dix)、馬克斯·貝克曼(Max Beckmann)和馬克·夏加爾(Marc

Chagall)的傑作。

由於德國官方拒絕公開沒收作品的清單,外界無法真正確定,去年沒收的作品裡,有沒有哪一幅是1950年歸還給希爾德布蘭特·古爾利特的畫作。不過,馬蘇洛夫斯基說,他相信,在盟軍於1950年歸還的畫作里,至少有一部分正是去年沒收的作品。

可以肯定的是,在1950年歸還的畫作中,至少有八幅實際上是被納

粹竊取的,而老古爾利特堅稱,他是通過合法途徑獲得這些畫的。目前這八幅畫被列入了一個被劫掠藝術品的數據庫,數據庫中列出的畫作在納粹佔領法國後,就存

放在了巴黎的國立網球場現代美術館(Jeu de Paume museum)。它們全都是法國畫家米歇爾·喬治-米歇爾(Michel

Georges-Michel)的作品,納粹特工在1941年洗劫了他的公寓和畫室。

盟軍追回的藝術品清單。

馬蘇洛夫斯基和其他追索專家表示,1950年的清單也許有助於鑒別德國最近從廓尼琉斯·古爾利特的公寓里沒收的作品。

在63年前歸還給希爾德布蘭特·古爾利特的其他畫作中,還有許多德

國表現主義畫家的作品,其中包括迪克斯的作品、喬治·格羅茲(George Grosz)的《行走中的一男兩女》(Two Women and a

Man Walking);埃里希·赫克爾(Erich Heckel)的作品、馬克斯·貝克曼(Max Beckmann)的《馴獅者》(Lion

Tamer)和《伐木者》(Woodcutters),克里斯蒂安·羅爾夫斯(Christian Rohlfs)的《黃花》(Yellow

Flowers)和《白花》(White Flowers),以及弗朗茨·倫克(Franz

Lenk)的作品。盟軍歸還的藝術品當中,也有意大利、法國和荷蘭大師們的作品,其中包括瓜爾迪(Guardi)的《修道院的大門》(Entrance

to a Monastery)、弗拉戈納爾(Fragonard)的《安娜和聖家庭》(Anna and the Holy

Family)、卡斯帕·內切爾(Caspar Netscher)的《吹泡泡的男孩》(Boys Blowing

Bubbles),以及據說作者是雷斯達爾(Ruysdael)和隆鮑茨(Rombouts)的風景畫。藏品里還有居斯塔夫·庫爾貝(Gustave

Courbet)的《父親》(The Father)和《有岩石的風景》(Landscape with Rocks);馬克斯·利伯曼(Max

Liebermann)的《沙丘上的馬車》(Wagon in the Dunes)和《沙灘上的騎馬者》(Two Riders on a

Beach)。

馬蘇洛夫斯基稱,這些畫作是「古迹衛士」會在無意之間歸還被劫掠藝術品的一個例子。

廓尼琉斯·古爾利特在2011年出售了馬克斯·貝克曼的《馴獅者》,這是當時出現在拍賣冊中的照片。

Wolfgang Rattay/Reuters

然而,歷史學者指出,在戰後歐洲一片混亂的背景下,尋找合法物主是極其困難的,當時既缺乏電腦數據庫的幫助,往往也沒有文檔記錄。例如,法國的博物館裡,仍存放着近2000件自知是劫掠而來的作品,但是無法穩妥地確認物主。

希爾德布蘭特·古爾利特是一名藝術史學者,因為外祖母是猶太人,他

曾兩次失去工作;儘管如此,他有德國把劫掠來的作品送到市場上出售所需的專業知識和國際關係網。戰爭期間,他還在納粹佔領區內四處探訪,尋找珍寶充實希特

拉(Hitler)在奧地利林茨建造一所博物館的宏偉計劃。檔案文件顯示,德國和美國調查人員曾在戰後就其交易行為審訊過古爾利特。不過他堅稱,所有留下

的藝術品都是他自己的。他說,他為納粹收集的其他作品,以及他自己的記錄,都在德累斯頓1945年遭受轟炸時被毀掉了。

至於被納粹形容為「墮落」的現代作品,許多已經被丟棄,或者被第三帝國(Third Reich)的博物館賣掉了,古爾利特及其他收藏者可能合法地取得了這些作品——價錢或許低得微不足道。

一幅新發現的馬蒂斯作品。

Christof Stache/Agence-France Presse â

迄今為止,從廓尼琉斯·古爾利特位於慕尼黑的骯髒公寓里沒收的

1400多幅畫作中,只有一幅的來源得到了明確核實。法國知名畫商保羅·羅森堡(Paul

Rosenberg)的孫女瑪麗安娜·羅森堡(Marianne

Rosenberg)確認,德國官員本周公布的一幅畫的照片和她的家族擁有的畫作相符,那幅畫是馬蒂斯(Matisse)的一幅肖像畫,畫中人是一名戴珍

珠項鏈的女子。(德國官方此前已經表示,至少有一幅畫曾經屬於羅森堡,他在自己所有藏品的背面都加蓋了自家畫廊的印鑒。)

瑪麗安娜·羅森堡在一封電子郵件中說,「當然,羅森堡家族很高興看

到馬蒂斯精美作品的彩色翻拍圖,直到現在,對我們來說,這幅作品都只是家中被劫掠藝術品檔案里的一張黑白照片。」她還說,她的家族「正在堅持不懈地認真推

動追索的進程」。不過,羅森堡家族依然堅持認為,德國官方必須儘快履行職責,「提供其他所有作品的照片和清單」。

翻譯:張薇

Documents Reveal How Looted Nazi Art Was Restored to Dealer

By PATRICIA COHENNovember 07, 2013

Throughout the waning years of

World War II, a band of Allied soldiers, art historians, curators and

scholars labored to safeguard Europe’s cultural heritage and recover the

millions of artworks and other treasures plundered by the Nazis and

their collaborators. Nicknamed the Monuments Men, this group set up a

string of temporary collection points for the valuables. Among the art

in their care was a cache of 115 paintings, 19 drawings and a half-dozen

crates of objects that the British had found in Hamburg in 1945. The

works were registered under the name of Hildebrand Gurlitt, according to

documents unearthed this week in the National Archives in College Park,

Md., by Marc Masurovsky, the founder of the Holocaust Art Restitution

Project.

Now, six decades later,

restitution experts said it is possible that this collection, once

entrusted to the Monuments Men, is part of the astonishing stash of more

than 1,400 works seized in 2012 by German investigators from the

apartment of Gurlitt’s son Cornelius and brought to light this week. It

is considered to be the largest trove of missing European art to have

been discovered since the end of World War II.

For five years, the elder

Gurlitt, one of a handful of German dealers whom the Nazis had anointed

to sell art confiscated from Jews and museums and sold abroad for

foreign currency, had insisted these works were rightfully his. With the

European recovery effort finally winding down, officials at a

collection center in Wiesbaden agreed to return the cache to Gurlitt.

On Dec. 15, 1950, the leader of

the Allied unit, Theodore Heinrich, an American, signed the papers

releasing the art to Gurlitt. The names and descriptions of a handful of

paintings in the cache returned to Hildebrand Gurlitt — including gems

by Otto Dix, Max Beckmann and Marc Chagall — appear to match those once

hidden in the cluttered apartment of his son.

Since the German authorities

have refused to make public a list of the seized works, it is impossible

to confirm with certainty that any of the pieces returned in 1950 to

Hildebrand Gurlitt are the same as those seized last year. Mr.

Masurovsky, however, said he believes that at least some of the works

returned by the Allies in 1950 are the same.

What can be confirmed is that

at least eight of the paintings that were returned in 1950, and that the

elder Gurlitt maintained he had legitimately acquired were, in fact,

stolen by the Nazis. These eight are currently listed in a database of

looted art that the Nazis had stored at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris

after they occupied France. Those works are all by the French painter

Michel Georges-Michel, whose apartment and studio were ransacked by Nazi

agents in 1941.

An Allied list of recovered art.

Mr. Masurovsky and other

restitution experts said the 1950 list might help with the

identification of works that the Germans recently took from Cornelius

Gurlitt’s apartment.

Among the other items returned

to Hildebrand Gurlitt 63 years ago were dozens of works by German

Expressionists including Dix, Georg Grosz (“Two Women and a Man

Walking”); Erich Heckel, Max Beckmann (“Lion Tamer” and “Woodcutters”),

Christian Rohlfs (“Yellow Flowers” and “White Flowers”) and Franz Lenk.

Italian, French and Dutch masters were on the Allied list, as well,

including Guardi’s “Entrance to a Monastery,” Fragonard’s “Anna and the

Holy Family,” Caspar Netscher’s “Boys Blowing Bubbles,” and landscapes

attributed to Ruysdael and Rombouts. The collection included Gustave

Courbet’s “The Father” and “Landscape with Rocks”; and Max Liebermann’s

“Wagon in the Dunes” and “Two Riders on a Beach.”

Mr. Masurovsky pointed to the return as an instance when the Monuments Men let looted art slip through their hands.

“The Lion Tamer” by Max Beckmann in an auction catalog when Cornelius Gurlitt sold it, in 2011.

Wolfgang Rattay/Reuters

Historians have pointed out,

however, that finding the legal owner in the confusion of postwar

Europe, without the aid of computerized databases and, often,

documentation, was extremely difficult. France, for example, still has

nearly 2,000 works in its museums that it knows were looted, but cannot

properly identify owners.

Hildebrand Gurlitt was an art

historian who had twice been stripped of posts because he had a Jewish

grandparent; nonetheless, he had the expertise and international

connections the Germans needed to move plundered works to market. He

also crisscrossed Nazi-occupied territory during the war looking for

treasures to fill Hitler’s grand plans for a museum in Linz, Austria.

German and American investigators had questioned Gurlitt about his

dealings after the war, archival documents show, but he insisted that

all of the art that remained was his own. Other works that he had

gathered for the Nazis, he said, as well as his records were destroyed

in the firebombing of Dresden in 1945.

As for the Modern works, which

the Nazis labeled degenerate, many had been discarded or sold off from

museums by the Third Reich and could have been legally acquired by

Gurlitt and other collectors — even for a pittance.

A newly rediscovered Matisse.

Christof Stache/Agence-France Presse â

So far only one among the more

than 1,400 works that were taken from Cornelius Gurlitt’s squalid Munich

apartment has been positively identified. Marianne Rosenberg, the

granddaughter of the renowned French dealer Paul Rosenberg, confirmed

that a photograph of a Matisse portrait of a woman wearing pearls that

was released by German officials this week matches one owned by her

family. (German authorities had previously said that at least one

painting used to belong to Rosenberg, who imprinted his gallery’s stamp

on the back of all his works.)

“The Rosenberg family is, of

course, delighted to see a color reproduction of the beautiful Matisse

which until now had only existed for them as a black and white

photograph in their archives of looted art,” Ms. Rosenberg said in an

email, adding that the family “is proceeding diligently and carefully

with a claim for restitution. The Rosenberg family still insists,

however, that the German authorities must promptly do the right thing

and provide photographs and lists of all the other items.”