Alain de Botton: How art can make us happier

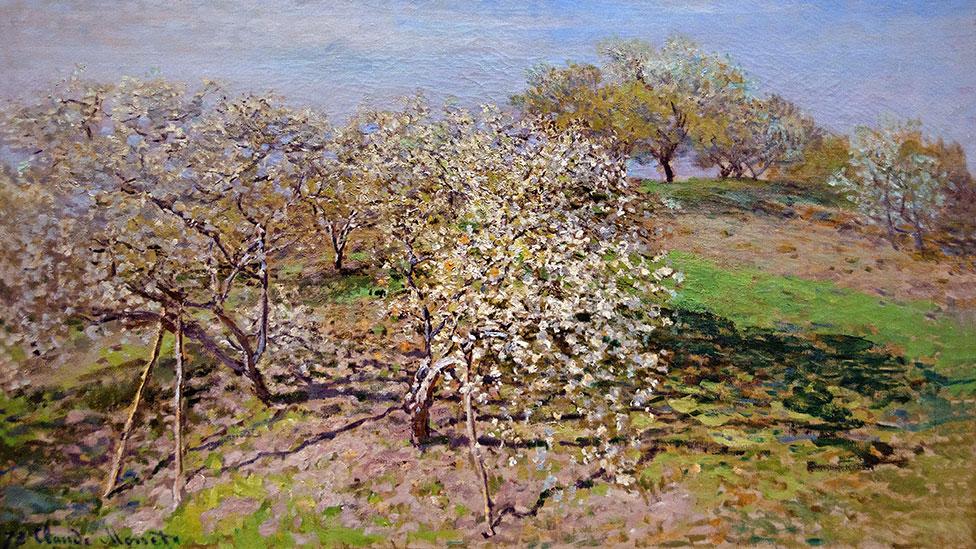

(Claude Monet/Phaidon)

By thinking too much and feeling too little, we are missing out on the

true enjoyment of art, philosopher Alain de Botton tells Alastiar Sooke.

Type

the words “Spring (Fruit Trees in Bloom)” into an online search engine

and in less than a second you will be looking at a sparkling vista of

trees erupting in a starburst of pale blossom like an exploding

firework. The phrase is the title of an Impressionist oil painting by

the French master Claude Monet that belongs to the Metropolitan Museum

of Art in New York.According to the museum’s website, the painting was executed in 1873 in Argenteuil, a village on the River Seine northwest of Paris where the Impressionist artists used to gather. Signed and dated “73 Claude Monet” in the lower left corner, it is almost 40in (1m) wide and 24.5in (62cm) high. In 1903, when it was known as Apple Blossoms, it was bought for $2,100 by the New York art dealership Knoedler & Co. The Met acquired it in 1926.

Concise, sober information like this is typical of the insights that museums commonly provide about artworks in their collections. Dates, dimensions, provenance: these are the bread and butter of scholarship and art history.

But by offering details about pictures in this manner, are museums fundamentally missing the point of what art is all about? One man who believes that they are is the British philosopher Alain de Botton, whose new book, Art as Therapy, co-written with the art theorist John Armstrong, is a polite but provocative demolition of the way that museums and galleries routinely present art to the public.

The way you make me feel

“Imagine an Impressionist picture,” de Botton tells me in his book-lined office in north-west London. “It’s a beautiful spring day in northern France and the flowers are out and the sky is blue. A lot of people might see it and say, ‘Ooh, is it a Manet or a Monet? I don’t know, I’m intimidated.’ I want to give viewers the courage to bring more of themselves to a work of art, and to ask them: what ultimately do you think? Is it a cheerful picture? If so, let’s not be embarrassed about that feeling.”

- (Phaidon)

“In the art world, the question, ‘What is art for?’ makes people uncomfortable,” explains de Botton, who has since been invited to re-caption works of art in three museums around the world: the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. (His new displays will open simultaneously next April.) “The art establishment downplays emotional or psychological readings of pictures – even though these are the principal ways in which people actually engage with art. But I think that you have to start with the emotional bond between the viewer and the object. If you say that a painting is important because it was owned by so-and-so, or because it shows that fascism is bad, or whatever – these are not reasons to love a painting.”

Does he feel, then, that art historians often get it all wrong? “Yes, absolutely,” he says. “The art-historical prejudice is that the more you know, the more you will be able to understand and feel. But I argue that while you need to know a little bit, the rewards tail off quickly. Doing a PhD [in art history] won’t necessarily bring you exponentially more pleasure or interest. Instead, art should be a form of therapy, which should be understood broadly as an aid to living and dying.”

Healthy scepticism

As its title suggests, de Botton’s book is a kind of self-help guide that explains how works of art and architecture can equip us to exist with greater equanimity and self-understanding. Each chapter is devoted to a different theme: love, nature, money, politics. Thus, according to de Botton, the plethora of precise little details in Hugo van der Goes’s The Adoration of the Shepherds (c.1475) should remind us that attentiveness to a lover’s quirks is an important part of what keeps a relationship alive. Richard Serra’s sorrowful sculpture Fernando Pessoa (2007-08) can teach us “how to suffer more successfully”, because it presents in monumental form the ubiquity and dignity of grief.

- (Hugo van der Goes/Phaidon)

A good example of this is their attitude towards philanthropic businessmen. “Artistic philanthropy feels weird,” de Botton tells me. “The classic model is the tycoon who has been squeezing his workers, abusing legislation, poisoning water wells, and so on – and at the end of his life, with his huge fortune, he buys a tender, beautiful work of art showing the mercy of the Virgin. The painting has been funded by a life that is utterly antithetical to the values in the picture. I believe that we should try to live the values in works of art every day, rather than at the very end when you buy that painting and give it to the Met.”

What, then, does de Botton make of the world-record price of more than $142 million achieved by Francis Bacon’s triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) at Christie’s in New York earlier this month, making it the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction? “Financial value and artistic value are separate,” he says. “Sometimes Vermeer is very valuable, and sometimes he’s not – but his paintings remain the same. So [with the price of the Bacon triptych] you learn a lot about society and economics and how taste is formed. But from the point of view of art, it means nothing.”

De Botton pauses, and a playful smile flickers across his lips. “A lot of emotional responses to art are available to people from a postcard,” he says. “This is an idea that museums are desperately resistant to, because the whole edifice immediately falls when you say that you can pick up between 80 and 90% [of what a work of art has to offer] by looking at a poster. I think we should start valuing art like literature. The original of, say, [James Joyce’s] Ulysses costs a certain amount and every other edition costs £9.99 – yet it’s considered fine to have the £9.99 copy. As punters, we are absurdly obsessed by original works of art – and we shouldn’t be.”

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph.

沒有留言:

張貼留言