In 1958 Georg Baselitz, then a 20-year-old art student recently arrived in West Berlin from East Germany, attended a touring exhibition of contemporary American

painting staged at his university. "Until then I had lived first under the Nazis, and then in the GDR," he explains. "Modern art just did not occur so I knew almost nothing. Not about German expressionism, dadaism, surrealism or even cubism. And suddenly here was abstract expressionism. Paintings by Pollock, De Kooning, Guston, Still and many others, in the very buildings where I took classes every day. It was overwhelming. And not just for me. Even the professors had not seen this sort of work before."

Baselitz recalls that the artist he most admired from the exhibition was Jackson Pollock, but the one he understood best was Willem de Kooning, "because he was European". It was a distinction that would characterise his wider response to the show, and point towards the idiosyncratic road his career would take.

"The exhibition was a great shock not just because of the art," he says, "but also because while we knew that the British, the French and the Russians had something like culture, we didn't expect it from the Americans. For us the Americans were just show-offs who had absolutely nothing to offer intellectually. But now they had not only won the war, they also had the culture. This show was meant as an educational event for us misguided Germans, after which art, and artistic society, was meant to find the correct way. And most of my fellow students really did take something from the American exhibition and became integrated into the entire thing."

But for Baselitz the show marked the beginning of a different path. "I had to make a decision what to do with this new information. I knew that we had lost the war, and that we were lost. And I now also realised that I was not welcome in this culture because I was not a modern person. What I wanted to do was something that totally contradicted internationalism: I wanted to examine what it was to be a German now. My teachers were the first to tell me that I was wrong. They said it was anachronistic. We had lost the war, but now we were free and liberated and there were wonderful times ahead in a wonderful world. But I disagreed. I had another view."

In truth Baselitz had always been going his own way. He had been forced out of East Germany after being accused by the authorities of "political immaturity" at his first art school. Five years after arriving in the west, his debut gallery show attracted the attention of the police and he was fined for displaying an obscene picture that apparently depicted a masturbating dwarf. In the years since, both Baselitz's art (a 1980 Venice biennale sculpture was accused of representing a Hitler salute) and his comments (last year he was quoted in an interview claiming that women artists "simply don't pass the test"), have caused controversy. But now, over half a century after that Berlin exhibition, and his refusal to join in with the artistic orthodoxy, Baselitz has returned to

Willem de Kooning in an exhibition entitled

Farewell Bill, which opens in the Gagosian Gallery in London this week.

The new paintings are a marked departure from recent works. Described as Remixes, these involved a riffing – apparently at great speed – on some of his most renowned previous paintings, and were greeted by a decidedly muted critical reaction. In contrast the De Kooning paintings – part self-portraits part homage – are large and attentively worked and, in a rare synchronicity of timing, form just one of three exhibitions in London over the next few months that feature different aspects of Baselitz's career. In March the

Royal Academy will stage Renaissance Impressions: Chiaroscuro Woodcuts from Baselitz's own collection, an important influence on both his style and subject matter. And

Germany Divided: Baselitz and His Generation has just opened at the British Museum, featuring works on paper from 1960 to the late 70s from the collection of Count Christian Duerckheim, who has recently donated to the museum a significant quantity of work by Baselitz, as well as by other German artists such as Markus Lüpertz, Sigmar Polke and

Gerhard Richter. Licht wil raum mecht hern. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: georg baselitz

Licht wil raum mecht hern. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: georg baselitz

All three shows cast light on Baselitz as simultaneously an international artist and an intensely German artist, reflecting the way his place on the global scene is always linked to his own past. "The German title of the De Kooning show is 'Willem raucht nicht mehr'", says Baselitz, speaking in his vast lakeside studio, designed by superstar architects Herzog & de Meuron, just outside Munich. "It literally translates as 'Willem no longer smokes', which also means in German 'is no longer alive'." The individual painting titles are anagrammatic variations on this phrase. "Sometimes they sound like children's language, or sometimes they sound like old German," he says, but as the catalogue essay notes, you might need to understand the Saxony dialect of his birthplace to get all the references. This is a very typical touch from an artist who says: "while I have always moved around a lot, I've always taken materials from that place with me. That's been important." One of the most important of those materials he has carried around is his own name.

Baselitz was born Hans-Georg Kern in 1938 in the Saxony town of Deutschbaselitz. As an art student in West Berlin he adopted the name of his home town, where his father was a primary school teacher and Nazi party member, and from where Baselitz can remember seeing Dresden burning in the distance after the firebombing of 1945. A few weeks after that event his family were sheltering in the basement of a building just outside the town when it was hit by artillery. During a pause in the shelling – "which we thought was a ceasefire, but was in fact just a breakfast break" – his mother loaded a handcart and set out with her children to escape the Russians advancing from the east. Smoke was still coming out of Dresden's destroyed buildings as they passed through the city, just one family among thousands of people trekking on foot across the country. "We wanted to get to Bavaria because we were told that the Americans were there. But we only made it to a village just to the south of Dresden when the Russians arrived."

By the time he was a teenager it was clear that Baselitz was not fitting into the GDR system and, after being expelled from art school, he effectively became an economic refugee. "When I stopped being a student I stopped getting vouchers that would allow me to buy groceries. I was told if I worked in industry for a year I could return to art school as I would by then have the right mindset. But I knew that would destroy me and so I chose to go to the west."

He describes himself as very "impatient" when he arrived in West Berlin. "I wanted to see results immediately and didn't start out reasonably, I started out radically." He wrote manifestos, one of which culminated with the line "All writing is crap." He found inspiration in the Prinzhorn Collection of art made by the inmates of a mental institution – some of which had figured in the Nazis' Degenerate Art exhibitions – and he embraced the psychologically extreme work of Antonin Artaud. Although he says it wasn't his intention to upset people, when his painting

The Big Night Down the Drain was seized by the police in 1963 he also realised "it was fun to do something that people would be upset about. But I also wanted to do something extraordinary and serious and I felt very privileged to have the artist's power to contradict. You feel like you are the founder of a new religion, even if your congregation is only your wife and kids."

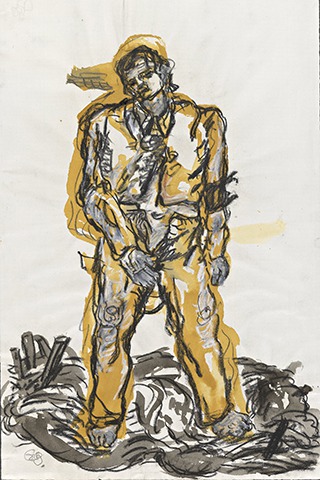

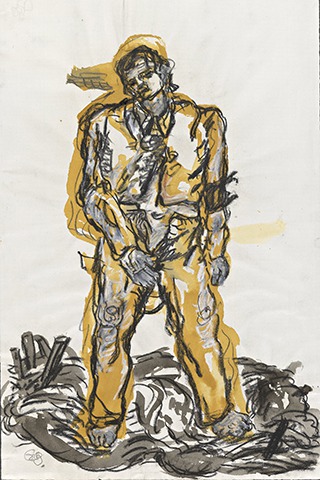

Baselitz had married Elke Kretzschmar in 1962 and they have two sons. He says that throughout most of the 60s "the chances for an artist, let alone an artist like me, to impose yourself and to make a living from your art was nil". But during this period his art made remarkable progress. Rejecting the orthodoxy of what was called tachism – the European version of abstract expressionism – he not only introduced figures into his work, but began to use specific German archetypes, motifs and folklore. But Baselitz's shepherds, woodsmen, hunters and so on were not conventionally heroic – although the paintings would later be called the Helden (heroes) series. Rather they were bedraggled, broken and shambolic figures rendered in messily desolate landscapes.

A New Type. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the British Museum

A New Type. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the British Museum

"In hindsight I think those pictures are complete pieces of art. But at the time it felt very chaotic and mixed up. I thought 'this can't be all' and I had to come up with new ideas." He set out on a series of strategies to disrupt both the work, and his making of the work. He painted with the canvas on the floor. (The floor of his studio closely resembles Jackson Pollock's on Long Island, with the difference that Baselitz doesn't insist that you wear protective shoes.) Then he started to "fracture" paintings into sections, with obvious echoes of a divided Germany, before he adopted the technique for which he is best known today, painting his motifs upside down – which directs both his, and the viewers, attention to the abstract aspects of the figurative work. He began to use his hands instead of brushes and when he moved to sculpting in wood he opted for the crude attack of the chainsaw over the precision chisel.

It was the row over his wooden sculpture at the 1980 Venice biennale that first brought him to an international audience. "I was in the German pavilion with Anselm Kiefer, another provocative artist, and it never occurred to me that my sculpture was doing a Hitler salute. But when a German TV channel reported on it they played the "Horst Wessel Song" [the Nazi anthem] to accompany their story. It was outrageous. But within a week I was getting approaches from all over the world to collaborate."

He says just being a German artist in the wider world could be contentious. "You sometimes felt that people were standing over you. Some of the prejudices that existed towards Germans were justified, but there were many prejudices. My work was also not really American-oriented, as Richter's is for example, and is instead very German and sometimes a bit obscene. Add that to being a kind of loud artist and then you will have encounters. Many of my advisers, especially my wife, say that I am too bold. But what am I supposed to do? Am I supposed to make statements that are politic? Am I supposed to be friendly? That's just not who I am."

No surprise then that he hasn't changed his mind about women artists. "Following the uproar I did think about this and it is a fact. I used to be a professor and 80% of my students were women. So there is a possibility for women and girls to study art, but they are less successful than the men. You can count and the numbers will prove me right." And he also casts a jaundiced eye over contemporary Germany, claiming it is rife with "injustice, vanity and dominance by the politicians" and hasn't yet properly dealt with its own history in terms of the Third Reich and the GDR. After reunification in 1990 he was not surprised to learn that the Stasi held a file on him, but was shocked that it was not for his correspondence with artists in the east when he was an adult, but his activities when at school. He is equally disillusioned with the stream of public intellectuals, such as Günter Grass, who took decades to acknowledge their membership of the SS. "These people dominated our culture. They were role models. They were mentioned in school textbooks. It is very depressing. It shows that no one is really free."

Willem raucht nicht mehr. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: Georg Baselitz

Willem raucht nicht mehr. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: Georg Baselitz

But for all his provocations about women artists, two of them played important roles in his return to De Kooning. "I saw Tracey Emin's drawing at the biennale. I like her very much, and as I looked at her drawings I thought here was De Kooning. I had also seen De Kooning in a Richard Prince exhibition at the Guggenheim. Cecily Brown, another artist I like, also gets inspiration from De Kooning. This was all very interesting. When I look at the new art scene I find there is a lot of direct occupation – that is, not a copy, but it seems as if the art of the past has become the foundation of the present. And so I said I'm going to paint like De Kooning."

Baselitz turned 76 last month and still works every day in the studio: "I used to be able to paint all day and all night, but these days it is only for three hours in the morning. Working the wood is especially hard work, but two trunks have just been delivered from the Black Forest, so there is more to do." His current work in progress is a series of six, four-metre high, nude self-portraits. "Every now and again I do a self-portrait, and always in quite a strange manner. There are many models for the nude self-portrait: Lucian Freud, Schiele, Stanley Spencer, whose painting I don't like, but I did see a pencil nude portrait that was interesting. In a way it is a move away from De Kooning, I knew I had to do something enormous and silly."

Licht wil raum mecht hern. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: georg baselitz

Licht wil raum mecht hern. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: georg baselitz A New Type. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the British Museum

A New Type. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the British Museum Willem raucht nicht mehr. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: Georg Baselitz

Willem raucht nicht mehr. Copyright Georg Baselitz. Courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery Photograph: Georg Baselitz