The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Celebrate the Feast of the Annunciation with this incredible altarpiece. Having just entered the room, the angel Gabriel is about to tell the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of Jesus.

Featured Artwork of the Day: Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444) | Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece) | ca. 1427–32 http://met.org/1U6RQ6x

Celebrate the Feast of the Annunciation with this incredible altarpiece. Having just entered the room, the angel Gabriel is about to tell the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of Jesus.

Featured Artwork of the Day: Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444) | Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece) | ca. 1427–32 http://met.org/1U6RQ6x

The Cimabues are teamed with four other small works, all from local museums. But there is plenty to look at, not the least because each involves multiple images. TheMetropolitan Museum of Art has lent a triptych by a Florentine contemporary of Cimabue, known only as the Magdalen Master, and a diptych by Pacino di Bonaguida, a younger follower, also represented by four images on vellum from the Morgan Library and Museum.

diptych, triptych

triptych

NOUN

Origin

Mid 18th century (denoting a set of three writing tablets hinged or tied together): from tri-'three', on the pattern of diptych.

Mid 18th century (denoting a set of three writing tablets hinged or tied together): from tri-'three', on the pattern of diptych.

diptych

NOUN

Origin

Early 17th century: via late Latin from late Greek diptukha 'pair of writing tablets', neuter plural of Greek diptukhos 'folded in two', from di- 'twice' + ptukhē 'a fold'.

Early 17th century: via late Latin from late Greek diptukha 'pair of writing tablets', neuter plural of Greek diptukhos 'folded in two', from di- 'twice' + ptukhē 'a fold'.

Updike on Art

‘Always Looking,’ by John Updike

Painting: Artist Rights

Society, New York/VG Bid-Kunst, Bonn; Digital image: Museum of Modern

Art, licensed by SCALA /Art Resource, NY

At the Guggenheim SoHo, Updike studied the Max Beckmann triptych "Departure" (1932-33).

By FRANCINE PROSE

Published: November 30, 2012

One of the most beautiful things ever written about visual art is

Zbigniew Herbert’s “Still Life With a Bridle,” a book-length study of

Dutch painting. Another is “The Birds of Paolo Uccello,” Italo Calvino’s

fanciful essay about why there aren’t more birds in the oeuvre

of a painter whose name means bird. To this list one could add Charles

Simic’s book on Joseph Cornell, “Dime-Store Alchemy,” and Mark Strand’s

monograph on Edward Hopper. And “Remembrance of Things Past” is full of

meditations on art that we may want to copy out and have embroidered on

samplers.

ALWAYS LOOKING

Essays on Art

By John Updike

Edited by Christopher Carduff

Illustrated. 204 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $45.

Related

Times Topic: John Updike

Obviously, these authors are novelists and poets, not professional art

critics. Just as obviously, there are plenty of art critics, historians

and curators — Ingrid Rowland, Sanford Schwartz, Dave Hickey, Robert

Storr and John Elderfield, to name a few — who not only write like

angels but can make you see art in entirely new ways.

But novelists and poets bring along, to the gallery or museum, a

particular set of skills. Having a gift for narrative and an eye for the

revelatory incident, novelists excel at swiftly but comprehensibly

guiding us through the high points of an artist’s life. Accustomed to

transmitting quantities of information without making readers feel

swamped by exposition, writers of fiction understand how to enliven

sections dense with fact. Obsessed with detail, poets and novelists

notice what is transpiring everywhere in a painting, and how each brush

stroke furthers the illusion that we are seeing a hand or a pearl

necklace. Most important, novelists and poets have had practice using

language to describe not only how something looks but the experience of

seeing it.

John Updike possessed all these gifts and more: the qualifications of a

novelist moonlighting as an art critic. He wrote lucidly and gracefully

and was acutely attentive to the visual world. “Always Looking,”

Updike’s third and last (he died in 2009) collection of essays about

art, includes reviews of museum exhibitions that he wrote for The New

York Review of Books and The New Republic, as well as “The Clarity of

Things,” the text of the Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities that Updike

delivered in Washington in 2008.

Each chapter contains a wealth of biographical, cultural and historical

knowledge that informs Updike’s responses to the artists whose work he

is considering: Magritte, Monet, Degas, Vuillard, Serra, among others.

At the Guggenheim Museum SoHo, he studies the Max Beckmann triptych

“Departure,” which has inspired so many variant interpretations. An

exhibition at the National Academy Museum in New York moves him to

reflect on America’s uneasy embrace of Surrealism: “American art in

general, whose primal memory is of the encounter with a hostile

wilderness, takes to surreal exaggerations and metaphors; but its

Puritan work ethic has little use for the playful self-indulgence

behind Parisian Surrealism.”

Having visited the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in

Williamstown, Mass., and marveled that a college-town museum should have

such an astoundingly first-rate collection, I was fascinated by

Updike’s account of its origins. The story, which suggests a Henry James

or Edith Wharton novel, involves two brothers, Sterling and Stephen

Clark, both collectors with passionate and dissimilar tastes; heirs to

the Singer sewing machine fortune, they stopped speaking after a

fistfight over the family trust. I was interested to learn that Joan

Miró was an admirer of Walt Whitman. I can’t decide whether I am glad to

know that Magritte’s mother drowned herself when he was 13.

Often, Updike’s descriptions of paintings do one of the most important

things that art writing can accomplish, which is to persuade the reader

to seek out, or take another look at, a painting or sculpture. Updike

sees the landmarks of 20th-century painting prefigured in a series of

1890 Degas monotypes of landscapes. And one is left with an intense

desire to view the originals, or at least more reproductions than can be

found even in this generously illustrated volume.

“Always Looking” (edited by Christopher Carduff) has passages of great

charm, several of which occur when Updike is describing the atmosphere

of a museum show. He captures the wry humor of seeing Gilbert Stuart’s

portraits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The next, sixth room is

the heart of the show, and the reason so many parents brought their

children. Fourteen portraits of the Father of Our Country in one great

custard-yellow room — a herd? a flock? a bevy? of George Washingtons!

Such a concentration has its comedy as well as a surreal grandeur. The

image is so familiar as to leave an art reviewer wordless. Even the

chirping children were momentarily hushed.” A very different atmosphere

surrounds the Richard Serra sculptures installed at the Museum of Modern

Art and mobbed with happy families enjoying “the biggest interactive

art event in Manhattan since Christo’s saffron flags fluttered in a

wintry Central Park over two years ago.”

Updike has strong, well-reasoned opinions that the reader may disagree

with, or not. I’ve always found myself fleeing Monet’s cathedral

paintings, and I was glad when Updike proposed a reason for my

disaffection. (“The Rouen facade is painted with an uncharacteristic

dry, lumpy, accretionary stroke, without fluency; the lacy stone details

are laboriously transformed into friable baguettes and dim ribs of

color.”) I admire the work of Vuillard more than Updike does, and that

of Magritte less, but whatever.

I would like to have known what Updike thought of Olana, the Victorian

Alhambra built above the Hudson River by the painter Frederic Church.

How would the novelist have responded to the over-the-top romanticism of

this Moorish folly, the product of a goofy Orientalist faith that

everything can be imported? But Updike settles for quoting the essayist

in the exhibition catalog who “can scarcely suppress the horror roused

in him by the Churches’ horror vacui” and to whom Olana evokes

“nothing so much as a silent-film set, minus a turbaned Douglas

Fairbanks Sr. bounding down the stairs.”

There are moments when one wishes that Updike had gone beyond the scope

of the exhibition on view. There’s a lovely paragraph at the end of the

review of a show on Monet in the 1890s in which he describes a painting

of a bridge arching over a waterlily pond: “The eye welcomes its

mathematical curve, abrupt as a Zen riddle, amid a wealth of fluid

appearance. As Monet continued for the rest of his life to paint the

waterlilies, he left out the helpful bridge, and modern art, in its

dominant tendencies, has walked on water since.” But one of Monet’s late

paintings, done in 1922, after he’d begun to lose his sight, depicts

the Japanese bridge. Executed in an autumnal palette of rusts and

oranges, far from the pastel beauty that Updike was looking at, more

like a van Gogh than what we usually think of as a Monet, it makes an

intriguing and affecting bookend to earlier images of the same scene.

The fact that John Updike’s essays engage the reader enough to agree or

argue with them is a testament to how vivid they are. Reading “Always

Looking,” we are grateful for the pleasure of having Updike’s eloquent

voice continue to tell us what he saw, and what he knew and thought

about art.

----

| Still Looking: Essays on American Art | 2005 | non-fiction |

1989年 John Updike 出版此藝術評論 JUST LOOKING: Essays on Art.

時 已出書30幾本

2008年初 還可以從網路找到這些參考資料

最特別的是此書在義大利印刷

與"作者介紹"同樣一整頁編幅的是 :"A Note on the Type"

From Publishers Weekly

The wit and sharp observation one expects from novelist/short story writer/poet/essayist Updike are found in these 23 pieces on art, supplemented by 193 plates. He offers trenchant views on Monet ("painting Nature in her nudity"); John Singer Sargent ("too facile"); Andrew Wyeth's "heavily hyped" series of Helga nudes; Degas's "patient invention of the snapshot before the camera itself was technically able to arrest motion and record the poetry of visual accident." He hops playfully from the "tender irony" of Richard Estes's hyperrealist Telephone Booths to a Vermeer townscape, and from children's book illustration to American children as depicted by Winslow Homer. He pauses to savor the unfamiliar or forgotten: Ralph Barton's wiry New Yorker cartoons, French sculptor Jean Ipousteguy's futuristic re-visioning of human anatomy, the elaborate, studied fantasies of churchgoing Yankee painter Erastus Salisbury Field.

Copyright 1989 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

2001年出平裝版

These 23 essays on traditional and modern art show John Updike at his most eclectic, entertaining, and enlightening. Originally published in 1989 and until now unavailable in any edition, Just Looking had become one of Updike's rarest and most sought-after titles. It collects the best of the novelist and critic's multifarious musings on art and artists, museums and popular culture, the lives behind the works and the ways in which these works have informed his own life. Included here are pieces on Vermeer, Erastus Field, Modigliani, the major Impressionists, New Yorker cartoonist Ralph Barton, children's book illustrations, Fairfield Porter, and Jean Ipousteguy, among others, as well as extensive reflections on John Singer Sargent and Andrew Wyeth, a critical examination of writers' art, and a long essay on his impressions of the Museum of Modern Art. Featuring a new introduction by the author, this edition of Just Looking-the first ever in paperback-brings back into print a key work of art criticism by one of the most respected and accomplished writers of our time and is the first in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston's new reprint series.

讀者在2000和2007年各有一篇"看法":

A Delightful and Beautiful Book,

A Delightful and Beautiful Book, July 22, 2007

In the 23 essays in JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART, John Updike is a delightful guide and insightful companion as he reviews art across the centuries. Throughout, Updike's voice is totally engaging, informed but never pedantic, respectful but not reverential. Here is a sample:

o "From his art, we might imagine him [Renoir] a plump, rosy, placid man, but in fact, he was bony-faced, nervous, reactionary, and restless."

o "This painting of Wertheimer tells us what we have been missing in even the more admirable of Sargent's portraits: an at-ease emotional possession of the subject that enables him to concentrate on making a painting. Where no warming familiarity exists, a certain distancing finesse takes over."

o "In 1944, Robert Motherwell wrote of his friend Jackson Pollock, `His principal problem is to discover what his true subject is. And since painting is his thought's medium, the resolution must grow out of the process of his painting itself.' Three years later, in sudden full stride, Pollock could state, `When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing.' Pollock painting is the subject of Pollock's paintings."

o "[Modigliani] ...drank while he painted and liked to complete a canvas in one sitting."

o "As his eyes increasingly dimmed, Degas perforce experimented with roughness of execution, never losing his underlying integrity of drawing."

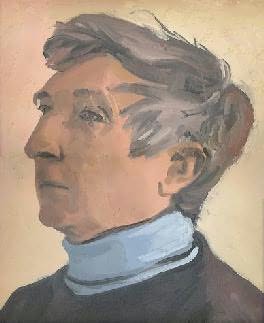

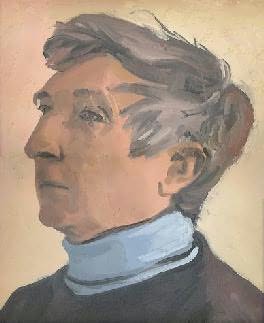

o "Faces gave [Fairfield] Porter a lot of trouble and his paint thickens as he worries over them."

JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART is also beautiful book with great reproductions. These tie seamlessly to Updike's commentary and enable the reader to fully appreciate his wonderful insights.

If you can't get to your local museum to visit the Vermeers (thank you, New York), this book is a superb alternative.

A Delightful and Beautiful Book,

A Delightful and Beautiful Book, July 22, 2007

In the 23 essays in JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART, John Updike is a delightful guide and insightful companion as he reviews art across the centuries. Throughout, Updike's voice is totally engaging, informed but never pedantic, respectful but not reverential. Here is a sample:

o "From his art, we might imagine him [Renoir] a plump, rosy, placid man, but in fact, he was bony-faced, nervous, reactionary, and restless."

o "This painting of Wertheimer tells us what we have been missing in even the more admirable of Sargent's portraits: an at-ease emotional possession of the subject that enables him to concentrate on making a painting. Where no warming familiarity exists, a certain distancing finesse takes over."

o "In 1944, Robert Motherwell wrote of his friend Jackson Pollock, `His principal problem is to discover what his true subject is. And since painting is his thought's medium, the resolution must grow out of the process of his painting itself.' Three years later, in sudden full stride, Pollock could state, `When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing.' Pollock painting is the subject of Pollock's paintings."

o "[Modigliani] ...drank while he painted and liked to complete a canvas in one sitting."

o "As his eyes increasingly dimmed, Degas perforce experimented with roughness of execution, never losing his underlying integrity of drawing."

o "Faces gave [Fairfield] Porter a lot of trouble and his paint thickens as he worries over them."

JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART is also beautiful book with great reproductions. These tie seamlessly to Updike's commentary and enable the reader to fully appreciate his wonderful insights.

If you can't get to your local museum to visit the Vermeers (thank you, New York), this book is a superb alternative.

紐約時報 書評

Date: October 15, 1989, Sunday, Late Edition - Final Section 7; Page 12, Column 1; Book Review Desk

Byline: By ARTHUR C. DANTO; Arthur C. Danto's books include ''Connections to the World: The Basic Concepts of Philosophy'' and the forthcoming ''Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present,'' a collection of critical essays.

Lead: LEAD: JUST LOOKING Essays on Art. By John Updike. Illustrated. 210 pp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. $35.

Text:

JUST LOOKING Essays on Art. By John Updike. Illustrated. 210 pp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. $35.

The matching of words to images was known as ekphrasis in ancient times, when the Greeks and Romans practiced it as a genre of literature. It went well beyond the mere description of pictures and statues, such as were given by the geographer and traveler Pausanias, who included accounts of these in the course of describing distant sites. Rather, it was the counterpart of illustration, made to fit to passages of poetry or prose images, with the picture conveying the same effect as the words.

The great set piece of ekphrasis is the verbal re-creation of the shield of Achilles in the ''Iliad,'' an account so stupendous that it is difficult not to suppose that Homer saw himself competing with the maker of the shield himself, though a god. A great ekphrasis is thus a work of art in its own right, but while Homer's word picture of the shield may be as dazzling as the shield itself would have been, it is impossible to imagine what the shield can have looked like from his description, and I have never seen a Greek vase painting of Achilles with his armor in which the artist even tried to show it. Botticelli undertook to re-create the lost ''Calumny'' of Apelles, perhaps the most famous painting of antiquity, from a brilliant ekphrasis by the poet Lucian, but the transit from words to pictures is sufficiently treacherous that, were the vanished masterpiece found tomorrow, it would resemble its Renaissance version only at the most abstract level. This cannot, of course, merely be because of the incommensurability of words and pictures; if all we knew of Homer were verbal paraphrases, however artful, of the books of the ''Odyssey,'' it would be unimaginable that the text itself could be generated from these. Nevertheless, finding the thousand words said to be equivalent to a single picture has continued to challenge writers with an extracurricular interest in the visual arts.

Given John Updike's intense interest in painting and sculpture - he attended the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford - ekphrasis presented itself as an inevitable further outlet for his polymorphous literary energies. A good many of the pieces collected in ''Just Looking'' put into characteristically fine language what the opulently reproduced images mean to him, and sometimes what they ought to mean to us. Ekphrastic description is after all something more and less than critical characterization of works of art. A critical account will make salient those features of a work that the critic then goes on to explain, together with some assessment of how successfully the artistic project addressed came out. Criticism yields enhanced understanding of the work, whereas ekphrasis often yields but enhanced understanding of the writer, and his or her preoccupations. Mr. Updike can be a very good art critic, and some of these essays are marvelous examples of critical explanation, in which the psychological concerns of the novelist drive the eye from work to work in an exhibition until a deep understanding of the art emerges.

His reviews of some recent and widely attended shows - of Renoir at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, of Sargent at the Whitney Museum of American Art, of Degas at the Metropolitan Museum and of the controverted ''Helga'' paintings by Andrew Wyeth - quite surpass the modest disclaimer of the title. ''Just looking'' is the phrase with which we identify ourselves to anxious clerks as idlers in a place where serious transactions take place. Rather, these pieces exemplify just looking, where ''just'' is an adjective of balanced deliberation, culminating in a verdict. Still, a good many of the essays really register the lookings of an artistic flaneur, who uses pictures as occasions for ruminative ekphrasis, much in the way in which the narrator in one of Mr. Updike's celebrated stories uses museums as metaphors for the women he memorializes in bittersweet cadences.

Mr. Updike's sensibility was defined by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in the period before that institution grew a luxury apartment and became as thronged as Bloomingdale's, and when the meaning of ''modern art'' was taught with reference to familiar images by Braque and Picasso, Miro and Arp, Rousseau and van Gogh and Modigliani. The introductory essay, ''What MOMA Done Tole Me,'' is an evocation of his life in that era, and of the value he drew from his visits to the museum. And some of the short essays surely transmit the lessons of individual works. The one on Modigliani's ''Reclining Nude'' is typical. It prompts a reflection on the ''tender white fronts'' of nude females, which cause him to think of a line from the theologian Karl Barth, that woman ''is in her whole existence an appeal to the kindness of man.'' The essay is genuinely ekphrastic in that it conveys through words the feeling about women that the canvas itself expresses. Indeed, the canvas, unglazed and exposed, strikes the author as vulnerable in a way that must be a projection of his feeling toward the sleeping naked woman. At the end of the essay he expresses gratitude that, perhaps because of a letter he wrote a museum director, the canvas was finally protected with glass, a solicitude that translates, one is certain, a tender concern for the too-exposed woman in the painting.

He was, he says of himself in those years, ''looking for a religion,'' so it is understandable that he should link art, sex and theology in meditating on this painting, and that what MOMA ''tole'' was a prophetic disclosure of ''gaiety, diligence, and freedom, a freedom from old constraints of perspective and subject matter, a freedom to embrace and memorialize the world anew.'' This is not the language of Artforum or October, Flash Art or Critical Inquiry. So it is not surprising that ''Op was the last art movement I enjoyed, and Minimalism the last one I was aware of.'' Nor is it surprising that he has little to say about abstract painting; the most he can say of a gingerly admired painting by Richard Diebenkorn is that it is ''an expensive variety of wallpaper,'' and the most it says to him is ''Have a nice day.'' The style wars of the last quarter of a century - Minimalism flourished in the middle 1960's, after all - can have little urgency for someone who sought, in art and sex, in museums and women, something that was taken away when the old-time religion died in his heart.

Neither will these essays hold great urgency for those whose concerns with art connect with the great critical issues of today. Still, for artists, past and present, whose concerns resonate with what Mr. Updike sought in those ''pious, joyful, and ignorant'' visits to what was called ''The Modern'' before ''MOMA'' became its name, he is exactly the writer to put words to their images. Some of the essays beyond question are as frivolous, slight and self-indulgent as the undergraduate caricatures he decided to reprint in a thin essay called ''Writers and Artists.'' These are cases of just looking. But sometimes everything in Mr. Updike's being is mobilized and he says something deep about works few critics are prepared to address save at the end of a 10-foot pole of condescending irony, like the ''Helga'' pictures. There he is looking with a just eye. BEAUTY WAS LEFT

For me the Museum of Modern Art was a temple where I might refresh my own sense of artistic purpose, though my medium had become words. What made this impudent array of color and form Art was the mystery; what made it Modern was obvious, and was the same force that made me modern: time. . . . But it was among the older and least ''modern'' works in the museum that I found most comfort, and the message I needed: that even though God and human majesty, as represented in the icons and triptychs and tedious panoramic canvases of older museums, had evaporated, beauty was still left, beauty amid our ruins, a beauty curiously pure, a blank uncaused beauty that signified only itself. Cezanne's ''Pines and Rocks,'' for instance, fascinated me, because its subject . . . was so obscurely deserving. . . . The ardor of Cezanne's painting shone most clearly through this curiously quiet piece of landscape, which he might have chosen by setting his easel down almost anywhere. . . . The Matisses, too, attracted me with their enigmatic solemnity. . . . How impudently, in ''Piano Lesson,'' does the painter take a wedge from the boy's round face, flip it over, and make of it a great green obelisk, barely explicable as a slice of lawn seen through a French door! I knew of nothing so arbitrary in writing - a regal whimsy enforced by the largeness of the painting, whose green was already cracking and aging in another kind of serene disregard. The little boy, but for the cruel wedge laid across his eye, looked normal to me, but the other figures - the little brown nude, the tall unfinished figure merging with her chair - were, I realize now, emissaries from another world: they were art twice over, representations of Matisse works already distributed in this domestic space. From ''Just Looking.''

時 已出書30幾本

2008年初 還可以從網路找到這些參考資料

最特別的是此書在義大利印刷

與"作者介紹"同樣一整頁編幅的是 :"A Note on the Type"

From Publishers Weekly

The wit and sharp observation one expects from novelist/short story writer/poet/essayist Updike are found in these 23 pieces on art, supplemented by 193 plates. He offers trenchant views on Monet ("painting Nature in her nudity"); John Singer Sargent ("too facile"); Andrew Wyeth's "heavily hyped" series of Helga nudes; Degas's "patient invention of the snapshot before the camera itself was technically able to arrest motion and record the poetry of visual accident." He hops playfully from the "tender irony" of Richard Estes's hyperrealist Telephone Booths to a Vermeer townscape, and from children's book illustration to American children as depicted by Winslow Homer. He pauses to savor the unfamiliar or forgotten: Ralph Barton's wiry New Yorker cartoons, French sculptor Jean Ipousteguy's futuristic re-visioning of human anatomy, the elaborate, studied fantasies of churchgoing Yankee painter Erastus Salisbury Field.

Copyright 1989 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

2001年出平裝版

These 23 essays on traditional and modern art show John Updike at his most eclectic, entertaining, and enlightening. Originally published in 1989 and until now unavailable in any edition, Just Looking had become one of Updike's rarest and most sought-after titles. It collects the best of the novelist and critic's multifarious musings on art and artists, museums and popular culture, the lives behind the works and the ways in which these works have informed his own life. Included here are pieces on Vermeer, Erastus Field, Modigliani, the major Impressionists, New Yorker cartoonist Ralph Barton, children's book illustrations, Fairfield Porter, and Jean Ipousteguy, among others, as well as extensive reflections on John Singer Sargent and Andrew Wyeth, a critical examination of writers' art, and a long essay on his impressions of the Museum of Modern Art. Featuring a new introduction by the author, this edition of Just Looking-the first ever in paperback-brings back into print a key work of art criticism by one of the most respected and accomplished writers of our time and is the first in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston's new reprint series.

讀者在2000和2007年各有一篇"看法":

| By | Ethan Cooper (Big Apple) - See all my reviews |

o "From his art, we might imagine him [Renoir] a plump, rosy, placid man, but in fact, he was bony-faced, nervous, reactionary, and restless."

o "This painting of Wertheimer tells us what we have been missing in even the more admirable of Sargent's portraits: an at-ease emotional possession of the subject that enables him to concentrate on making a painting. Where no warming familiarity exists, a certain distancing finesse takes over."

o "In 1944, Robert Motherwell wrote of his friend Jackson Pollock, `His principal problem is to discover what his true subject is. And since painting is his thought's medium, the resolution must grow out of the process of his painting itself.' Three years later, in sudden full stride, Pollock could state, `When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing.' Pollock painting is the subject of Pollock's paintings."

o "[Modigliani] ...drank while he painted and liked to complete a canvas in one sitting."

o "As his eyes increasingly dimmed, Degas perforce experimented with roughness of execution, never losing his underlying integrity of drawing."

o "Faces gave [Fairfield] Porter a lot of trouble and his paint thickens as he worries over them."

JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART is also beautiful book with great reproductions. These tie seamlessly to Updike's commentary and enable the reader to fully appreciate his wonderful insights.

If you can't get to your local museum to visit the Vermeers (thank you, New York), this book is a superb alternative.

| By | Ethan Cooper (Big Apple) - See all my reviews |

o "From his art, we might imagine him [Renoir] a plump, rosy, placid man, but in fact, he was bony-faced, nervous, reactionary, and restless."

o "This painting of Wertheimer tells us what we have been missing in even the more admirable of Sargent's portraits: an at-ease emotional possession of the subject that enables him to concentrate on making a painting. Where no warming familiarity exists, a certain distancing finesse takes over."

o "In 1944, Robert Motherwell wrote of his friend Jackson Pollock, `His principal problem is to discover what his true subject is. And since painting is his thought's medium, the resolution must grow out of the process of his painting itself.' Three years later, in sudden full stride, Pollock could state, `When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing.' Pollock painting is the subject of Pollock's paintings."

o "[Modigliani] ...drank while he painted and liked to complete a canvas in one sitting."

o "As his eyes increasingly dimmed, Degas perforce experimented with roughness of execution, never losing his underlying integrity of drawing."

o "Faces gave [Fairfield] Porter a lot of trouble and his paint thickens as he worries over them."

JUST LOOKING: ESSAYS ON ART is also beautiful book with great reproductions. These tie seamlessly to Updike's commentary and enable the reader to fully appreciate his wonderful insights.

If you can't get to your local museum to visit the Vermeers (thank you, New York), this book is a superb alternative.

紐約時報 書評

WHAT MOMA DONE TOLE HIM

Date:Byline:

Lead:

Text:

JUST LOOKING Essays on Art. By John Updike. Illustrated. 210 pp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. $35.

The matching of words to images was known as ekphrasis in ancient times, when the Greeks and Romans practiced it as a genre of literature. It went well beyond the mere description of pictures and statues, such as were given by the geographer and traveler Pausanias, who included accounts of these in the course of describing distant sites. Rather, it was the counterpart of illustration, made to fit to passages of poetry or prose images, with the picture conveying the same effect as the words.

The great set piece of ekphrasis is the verbal re-creation of the shield of Achilles in the ''Iliad,'' an account so stupendous that it is difficult not to suppose that Homer saw himself competing with the maker of the shield himself, though a god. A great ekphrasis is thus a work of art in its own right, but while Homer's word picture of the shield may be as dazzling as the shield itself would have been, it is impossible to imagine what the shield can have looked like from his description, and I have never seen a Greek vase painting of Achilles with his armor in which the artist even tried to show it. Botticelli undertook to re-create the lost ''Calumny'' of Apelles, perhaps the most famous painting of antiquity, from a brilliant ekphrasis by the poet Lucian, but the transit from words to pictures is sufficiently treacherous that, were the vanished masterpiece found tomorrow, it would resemble its Renaissance version only at the most abstract level. This cannot, of course, merely be because of the incommensurability of words and pictures; if all we knew of Homer were verbal paraphrases, however artful, of the books of the ''Odyssey,'' it would be unimaginable that the text itself could be generated from these. Nevertheless, finding the thousand words said to be equivalent to a single picture has continued to challenge writers with an extracurricular interest in the visual arts.

Given John Updike's intense interest in painting and sculpture - he attended the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford - ekphrasis presented itself as an inevitable further outlet for his polymorphous literary energies. A good many of the pieces collected in ''Just Looking'' put into characteristically fine language what the opulently reproduced images mean to him, and sometimes what they ought to mean to us. Ekphrastic description is after all something more and less than critical characterization of works of art. A critical account will make salient those features of a work that the critic then goes on to explain, together with some assessment of how successfully the artistic project addressed came out. Criticism yields enhanced understanding of the work, whereas ekphrasis often yields but enhanced understanding of the writer, and his or her preoccupations. Mr. Updike can be a very good art critic, and some of these essays are marvelous examples of critical explanation, in which the psychological concerns of the novelist drive the eye from work to work in an exhibition until a deep understanding of the art emerges.

His reviews of some recent and widely attended shows - of Renoir at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, of Sargent at the Whitney Museum of American Art, of Degas at the Metropolitan Museum and of the controverted ''Helga'' paintings by Andrew Wyeth - quite surpass the modest disclaimer of the title. ''Just looking'' is the phrase with which we identify ourselves to anxious clerks as idlers in a place where serious transactions take place. Rather, these pieces exemplify just looking, where ''just'' is an adjective of balanced deliberation, culminating in a verdict. Still, a good many of the essays really register the lookings of an artistic flaneur, who uses pictures as occasions for ruminative ekphrasis, much in the way in which the narrator in one of Mr. Updike's celebrated stories uses museums as metaphors for the women he memorializes in bittersweet cadences.

Mr. Updike's sensibility was defined by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in the period before that institution grew a luxury apartment and became as thronged as Bloomingdale's, and when the meaning of ''modern art'' was taught with reference to familiar images by Braque and Picasso, Miro and Arp, Rousseau and van Gogh and Modigliani. The introductory essay, ''What MOMA Done Tole Me,'' is an evocation of his life in that era, and of the value he drew from his visits to the museum. And some of the short essays surely transmit the lessons of individual works. The one on Modigliani's ''Reclining Nude'' is typical. It prompts a reflection on the ''tender white fronts'' of nude females, which cause him to think of a line from the theologian Karl Barth, that woman ''is in her whole existence an appeal to the kindness of man.'' The essay is genuinely ekphrastic in that it conveys through words the feeling about women that the canvas itself expresses. Indeed, the canvas, unglazed and exposed, strikes the author as vulnerable in a way that must be a projection of his feeling toward the sleeping naked woman. At the end of the essay he expresses gratitude that, perhaps because of a letter he wrote a museum director, the canvas was finally protected with glass, a solicitude that translates, one is certain, a tender concern for the too-exposed woman in the painting.

He was, he says of himself in those years, ''looking for a religion,'' so it is understandable that he should link art, sex and theology in meditating on this painting, and that what MOMA ''tole'' was a prophetic disclosure of ''gaiety, diligence, and freedom, a freedom from old constraints of perspective and subject matter, a freedom to embrace and memorialize the world anew.'' This is not the language of Artforum or October, Flash Art or Critical Inquiry. So it is not surprising that ''Op was the last art movement I enjoyed, and Minimalism the last one I was aware of.'' Nor is it surprising that he has little to say about abstract painting; the most he can say of a gingerly admired painting by Richard Diebenkorn is that it is ''an expensive variety of wallpaper,'' and the most it says to him is ''Have a nice day.'' The style wars of the last quarter of a century - Minimalism flourished in the middle 1960's, after all - can have little urgency for someone who sought, in art and sex, in museums and women, something that was taken away when the old-time religion died in his heart.

Neither will these essays hold great urgency for those whose concerns with art connect with the great critical issues of today. Still, for artists, past and present, whose concerns resonate with what Mr. Updike sought in those ''pious, joyful, and ignorant'' visits to what was called ''The Modern'' before ''MOMA'' became its name, he is exactly the writer to put words to their images. Some of the essays beyond question are as frivolous, slight and self-indulgent as the undergraduate caricatures he decided to reprint in a thin essay called ''Writers and Artists.'' These are cases of just looking. But sometimes everything in Mr. Updike's being is mobilized and he says something deep about works few critics are prepared to address save at the end of a 10-foot pole of condescending irony, like the ''Helga'' pictures. There he is looking with a just eye. BEAUTY WAS LEFT

For me the Museum of Modern Art was a temple where I might refresh my own sense of artistic purpose, though my medium had become words. What made this impudent array of color and form Art was the mystery; what made it Modern was obvious, and was the same force that made me modern: time. . . . But it was among the older and least ''modern'' works in the museum that I found most comfort, and the message I needed: that even though God and human majesty, as represented in the icons and triptychs and tedious panoramic canvases of older museums, had evaporated, beauty was still left, beauty amid our ruins, a beauty curiously pure, a blank uncaused beauty that signified only itself. Cezanne's ''Pines and Rocks,'' for instance, fascinated me, because its subject . . . was so obscurely deserving. . . . The ardor of Cezanne's painting shone most clearly through this curiously quiet piece of landscape, which he might have chosen by setting his easel down almost anywhere. . . . The Matisses, too, attracted me with their enigmatic solemnity. . . . How impudently, in ''Piano Lesson,'' does the painter take a wedge from the boy's round face, flip it over, and make of it a great green obelisk, barely explicable as a slice of lawn seen through a French door! I knew of nothing so arbitrary in writing - a regal whimsy enforced by the largeness of the painting, whose green was already cracking and aging in another kind of serene disregard. The little boy, but for the cruel wedge laid across his eye, looked normal to me, but the other figures - the little brown nude, the tall unfinished figure merging with her chair - were, I realize now, emissaries from another world: they were art twice over, representations of Matisse works already distributed in this domestic space. From ''Just Looking.''

沒有留言:

張貼留言