包豪斯 當代設計的搖籃 李亮之 黑龍江美術,2008

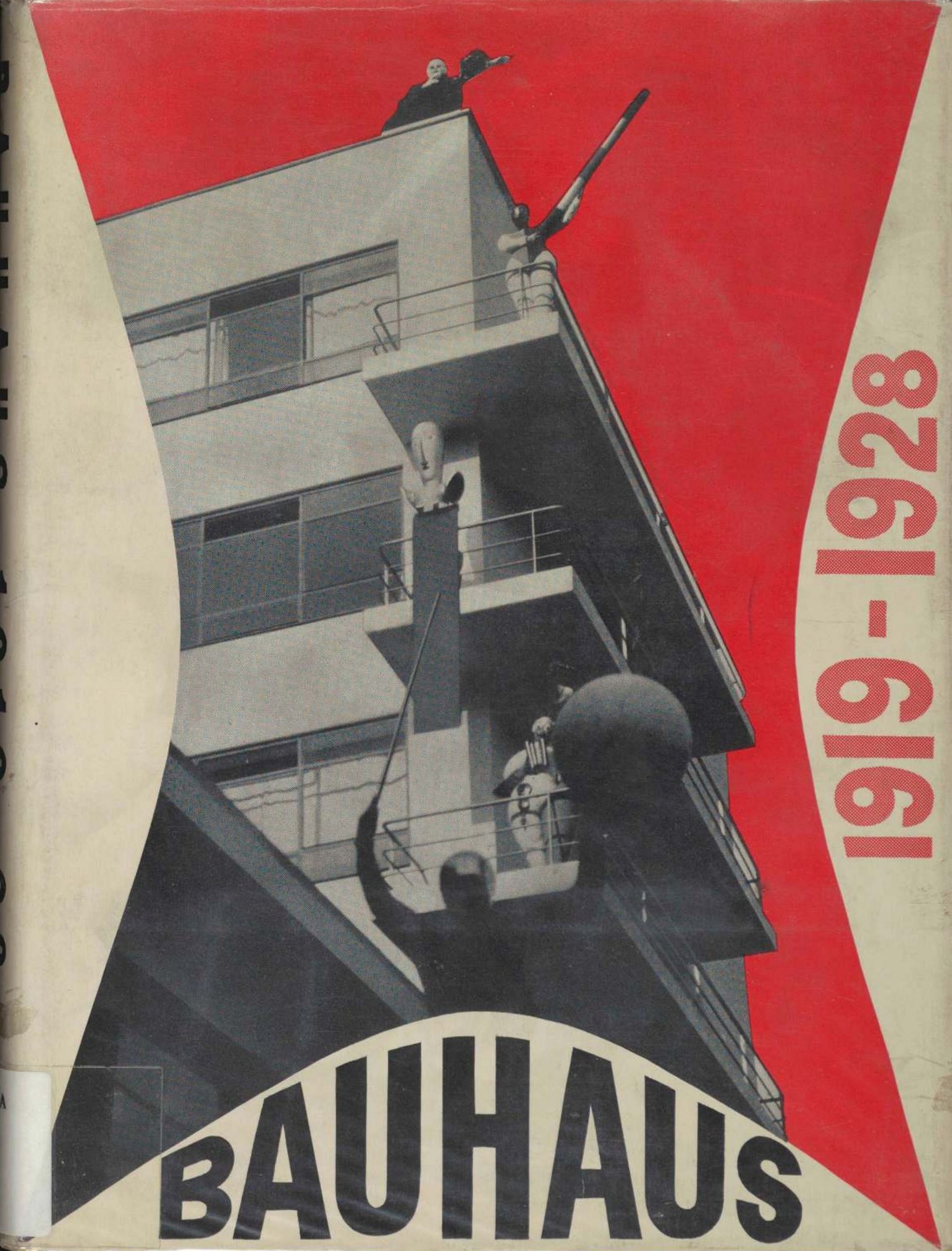

Bauhaus, 1919-1928 / Edited by Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius. — New York, 1938

http://tehne.com/library/bauhaus-1919-1928-edited-herbert-bayer-walter-gropius-ise-gropius-new-york-1938

Bauhaus, 1919-1928 / Edited by Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius (Chairman of the Department of Architecture, Harvard University). — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1938. — 224 p., ill.

In 1938 MoMA issued a press memo informing New York City editors that on December 7, the Museum would open “what will probably be considered its most unusual exhibition—and certainly one of its largest.” That exhibition was Bauhaus: 1919–1928, an expansive survey dedicated to this incomparably influential German school of art and design. On display were nearly 700 examples of the school’s output, including works of textile, glass, wood, canvas, metal, and paper. It was a celebration of the remarkable creativity and productivity of the Bauhaus, which had been forced to close under pressure from the Nazi Party just five years prior. The size and scope of this tribute indicated the importance of the Bauhaus to MoMA's development: the school had served as a model for the Museum’s multi-departmental structure, and inspired its multidisciplinary presentation of photography, architecture, painting, graphic design, and theater.

WHAT is the Bauhaus?

The Bauhaus is an answer to the question: how can the artist be trained to take his place in the machine age.

HOW did the Bauhaus Idea begin?

As a school which became the most important and influential institution of its kind in modern times.

WHERE?

In Germany, first at Weimar, then at Dessau.

WHEN?

From 1919 until closed by the National Socialists in 1933.

WHO were its teachers?

Walter Gropius, its founder and first director, Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger, Schlemmer, Itten, Moholy-Nagy, Albers, Bayer, Breuer, and others.

WHAT did they teach?

Architecture, housing, painting, sculpture, photography, cinema, theatre, ballet, industrial design, pottery, metal work, textiles, advertising, typography and, above all, a modern philosophy of design.

WHY Is the Bauhaus so important?

- Because it courageously accepted the machine as an instrument worthy of the artist.

- Because it faced the problem of good design for mass production.

- Because it brought together on its faculty more artists of distinguished talent than has any other art school of our time.

- Because it bridged the gap between the artist and the industrial system.

- Because it broke down the hierarchy which had divided the "fine" from the "applied" arts.

- Because it differentiated between what can be taught (technique) and what cannot (creative invention).

- Because its building at Dessau was architecturally the most important structure of the 1920's.

- Because after much trial and error it developed a new and modern kind of beauty.

- And, finally, because its influence has spread throughout the world, and is especially strong today in England and the United States.

PREFACE

It is twenty years since Gropius arrived in Weimar to found the Bauhaus; ten years since he left the transplanted and greatly enlarged institution at Dessau to return to private practice: five years since the Bauhaus was forced to close its doors after a brief rear-guard stand in Berlin.

Are this book, then, and the exhibition which supplements it, merely a belated wreath laid upon the tomb of brave events, important in their day but now of primarily historical interest? Emphatically, no! The Bauhaus is not dead; it lives and grows through the men who made it, both teachers and students, through their designs, their books, their methods, their principles, their philosophies of art and education.

It is hard to recall when and how we in America first began to hear of the Bauhaus. In the years just after the War we thought of German art in terms of Expressionism, of Mendelsohn’s streamlined Einstein tower, Toller's Masse Mensch, Wiene's Cabinet ot Dr. Caligari. It may not have been until after the great Bauhaus exhibition of 1923 that reports reached America of a new kind of art school in Germany where famous expressionist painters such as Kandinsky were combining forces with craftsmen and industrial designers under the general direction of the architect, Gropius. A little later we began to see some of the Bauhaus books, notably Schlemmer’s amazing volume on the theatre and Moholy-Nagy's Malerei, Phoiographie, Film.

Some of the younger of us had just left colleges where courses in modern art began with Rubens and ended with a few superficial and often hostile remarks about van Gogh and Matisse; where the last word in imitation Gothic dormitories had windows with one carefully cracked pane to each picturesque casement. Others of us, in architectural schools, were beginning our courses with gigantic renderings of Doric capitals, or ending them with elaborate projects for colonial gymnasiums and Romanesque skyscrapers. The more radical American architects and designers in 1925, ignoring Frank Lloyd Wright, turned their eyes toward the eclectic "good taste" of Swedish "modern" and the trivial bad taste of Paris "modernistic." It is shocking to recall that only one year later the great new Bauhaus building at Dessau was completed.

It is no wonder then that young Americans began to turn their eyes toward the Bauhaus as the one school in the world where modern problems of design were approached realistically in a modern atmosphere. A few American pilgrims had visited Dessau before Gropius left in 1928; in the five years thereafter many went to stay as students. During this time Bauhaus material, typography, paintings, prints, theatre art, architecture, industrial objects, had been included in American exhibitions though nowhere so importantly as in the Paris Salon des Artistes Décorateurs of 1930. There the whole German section was arranged under the direction of Gropius. Consistent in program, brilliant in installation, it stood like an island of integrity, in a mélange of chaotic modernistic caprice, demonstrating (what was not generally recognized at that time) that German industrial design, thanks largely to the Bauhaus, was years ahead of the rest of the world.

And the rest of the world began to accept the Bauhaus. In America Bauhaus lighting fixtures and tubular steel chairs were imported or the designs pirated. American Bauhaus students began to return; and they were followed, alter the revolution of 1933, by Bauhaus and ex-Bauhaus masters who suffered from the new government's illusion that modern furniture, flat-roofed architecture and abstract painting were degenerate or bolshevistic. In this way, with the help of the fatherland, Bauhaus designs, Bauhaus men, Bauhaus ideas, which taken together form one of the chief cultural contributions of modern Germany, have been spread throughout the world.

This is history. But, one may ask, what have we in America today to learn from the Bauhaus? Times change and ideas of what constitutes modern art or architecture or education shift with bewildering rapidity. Many Bauhaus designs which were once five years ahead of their time seem now, ten years afterward, to have taken on the character of period pieces. And some of its ideas are no longer so useful as they once were. But this inevitable process of obsolescence was even more active in the Bauhaus while it still existed as an institution for, as Gropius has often Insisted, the idea of a Bauhaus style or a Bauhaus dogma as something fixed and permanent was at all times merely the inaccurate conclusion of superficial observers.

Looking back we can appreciate more fully than ever certain magnificent achievements of the Bauhaus which are so obvious that they might be overlooked. It is only eight years since the I920's come to an end yet I think we can now say without exaggeration that the Bauhaus building at Dessau was architecturally the most important structure of its decade. And we can ask if in modern times there have ever been so many men of distinguished talent on the faculty of any other art school or academy. And though the building is now adorned with a gabled roof and the brilliant teaching force has been dispersed there are certain methods and ideas developed by the Bauhaus which we may still ponder. There are, for instance, the Bauhaus principles:

- that most students should face the fact that their future should be involved primarily with industry and mass production rather than with individual craftsmanship;

- that teachers in schools of design should be men who are in advance of their profession rather than safely and academically in the rearguard;

- that the school of design should, as the Bauhaus did, bring together the various arts of painting, architecture, theatre, photography, weaving, typography, etc., into a modern synthesis which disregards conventional distinctions between the "fine" and "applied" arts;

- that it is harder to design a first rate chair than to paint a second rate painting—and much more useful;

- that a school of design should have on its faculty the purely creative and disinterested artist such as the easel painter as a spiritual counterpoint to the practical technician in order that they may work and teach side by side for the benefit of the student;

- that thorough manual experience of materials is essential to the student of design—experience at first confined to free experiment and then extended to practical shop work;

- that the study of rational design in terms of technics and materials should be only the first step in the development of a new and modern sense of beauty.

- and, lastly, that because we live in the 20th century, the student architect or designer should be offered no refuge in the past but should be equipped for the modern world in its various aspects, artistic, technical, social, economic, spiritual, so that he may function in society not as a decorator but as a vital participant.

This book on the Bauhaus is published in conjunction with the Museum's exhibition, Bauhaus 1919-28. Like the exhibition it is for the most part limited to the first nine years of the institution, the period during which Gropius was director. For reasons beyond the control of any of the individuals involved, the last five years of the Bauhaus could not be represented. During these five years much excellent work was done and the international reputation of the Bauhaus increased rapidly, but, fortunately for the purposes of this book, the fundamental character of the Bauhaus had already been established under Gropius' leadership.

This book is primarily a collection of evidence—photographs, articles and notes done on the field of action, and assembled here with a minimum of retrospective revision. It Is divided into two parts: Weimar, 1919-1925, and Dessau, 1925-1928. These divisions indicate more than a change of location and external circumstances, for although the expressionist and, later, formalistic experiments at Weimar were varied and exciting it may be said that the Bauhaus really found itself only after the move to Dessau. This book is not complete, even within its field, for some material could not be brought out of Germany. At some time a definitive work on the Bauhaus should be written, a well-ordered, complete and carefully documented history prepared by a dispassionate authority, but time and other circumstances make this impossible at present. Nevertheless this book, prepared by Herbert Bayer under the general editorship of Professor Gropius and with the generous collaboration of a dozen Bauhaus teachers, is by far the most complete and authoritative account of the Bauhaus so far attempted.

The exhibition has been organized and installed by Herbert Bayer with the assistance of the Museum's Department of Architecture and Industrial Art.

The Museum of Modern Art wishes to thank especially Herbert Bayer for his difficult, extensive and painstaking work in assembling and installing the exhibition and laying out this book; Professor Walter Gropius, of the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, for his supervision of the book and exhibition; Mrs. Ise Gropius for her assistance in editing the book; Alexander Schawinsky, formerly of the Bauhaus, and Josef Albers, Professor of Art at Black Mountain College and formerly of the Bauhaus, for their help in preparing the exhibition.

Also Miss Sara Babbitt, Mrs. John W. Lincoln, Mr. Paul Grotz, Mr. Philip Johnson and Mr. Brinton Sherwood, who, as volunteers, have assisted Mr. Bayer and the Museum staff; also those who have generously lent material to the exhibition and contributed photographs for reproduction in the book.

The Museum assumes full responsibility for having invited Professor Gropius, Mr. Bayer, and their colleagues to collaborate in the book and its accompanying exhibition. All the material included in the exhibition has been lent at the Museum's request, in some cases without the consent of the artist.*

____________

* The work of many artists in this book is being shown without their consent. When the book was at the point of going to press it was considered advisable to delete the names of several of these artists.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Director

CONTENTS

Preface by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. 7

The Background of the Bauhaus by Alexander Dorner 11

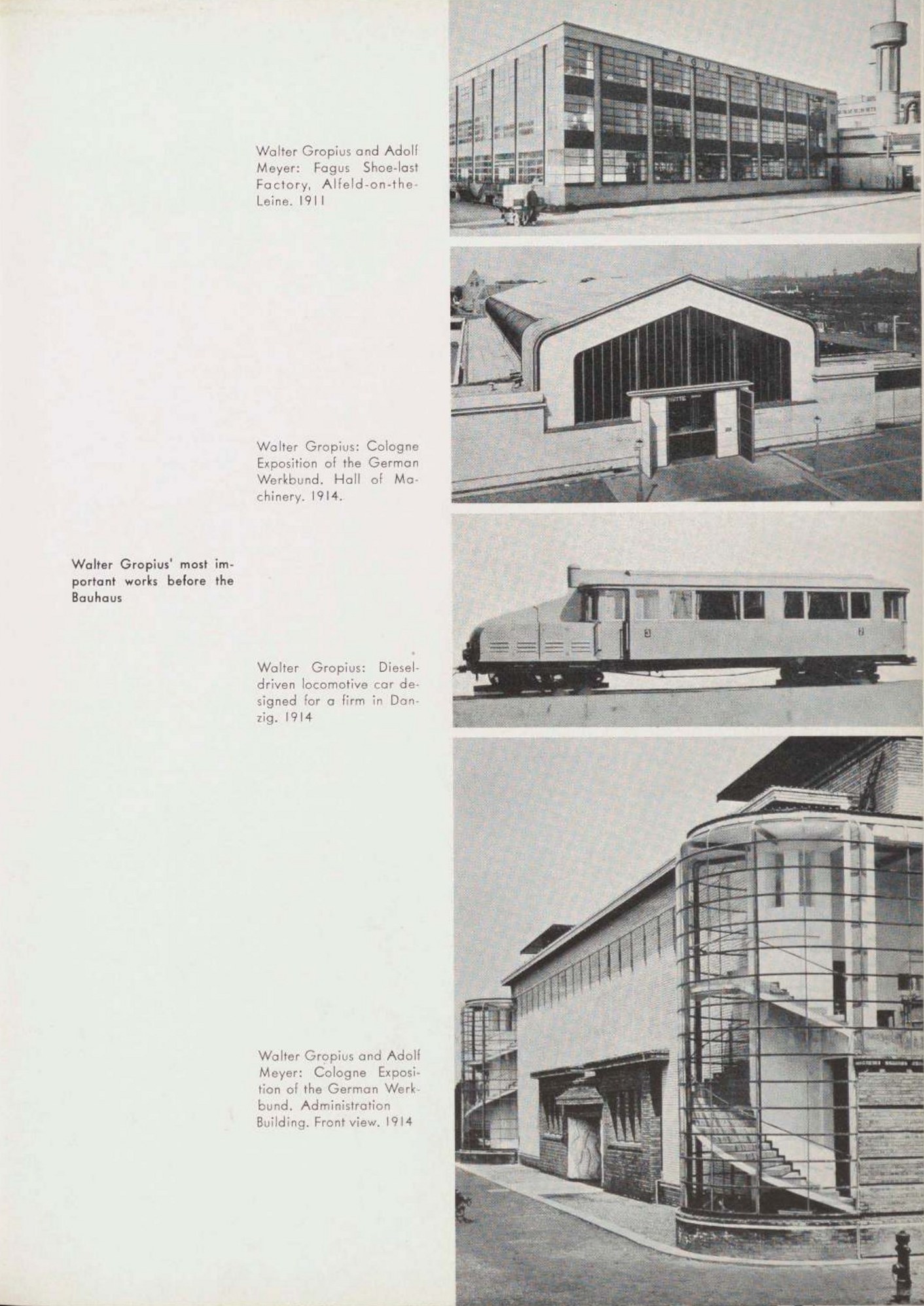

Walter Gropius—Biographical Note 16

WEIMAR BAUHAUS 1919-1925

From the First Proclamation 18

Teachers and Students 20

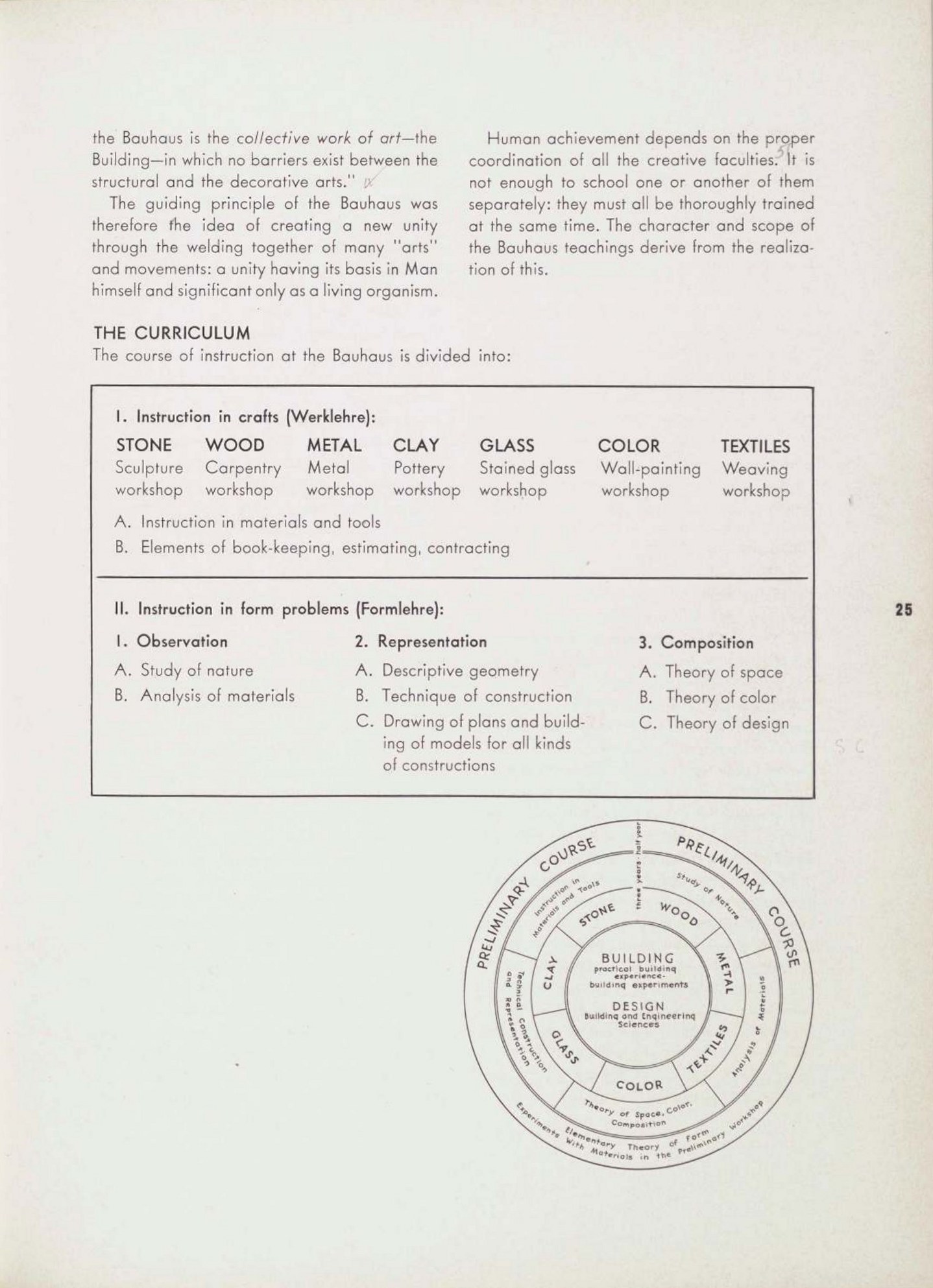

The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius (Weimar, 1923) 22

Preliminary Course: Itten 32

Klee's Course 39

Kandinsky's Course 40

Color Experiments 41

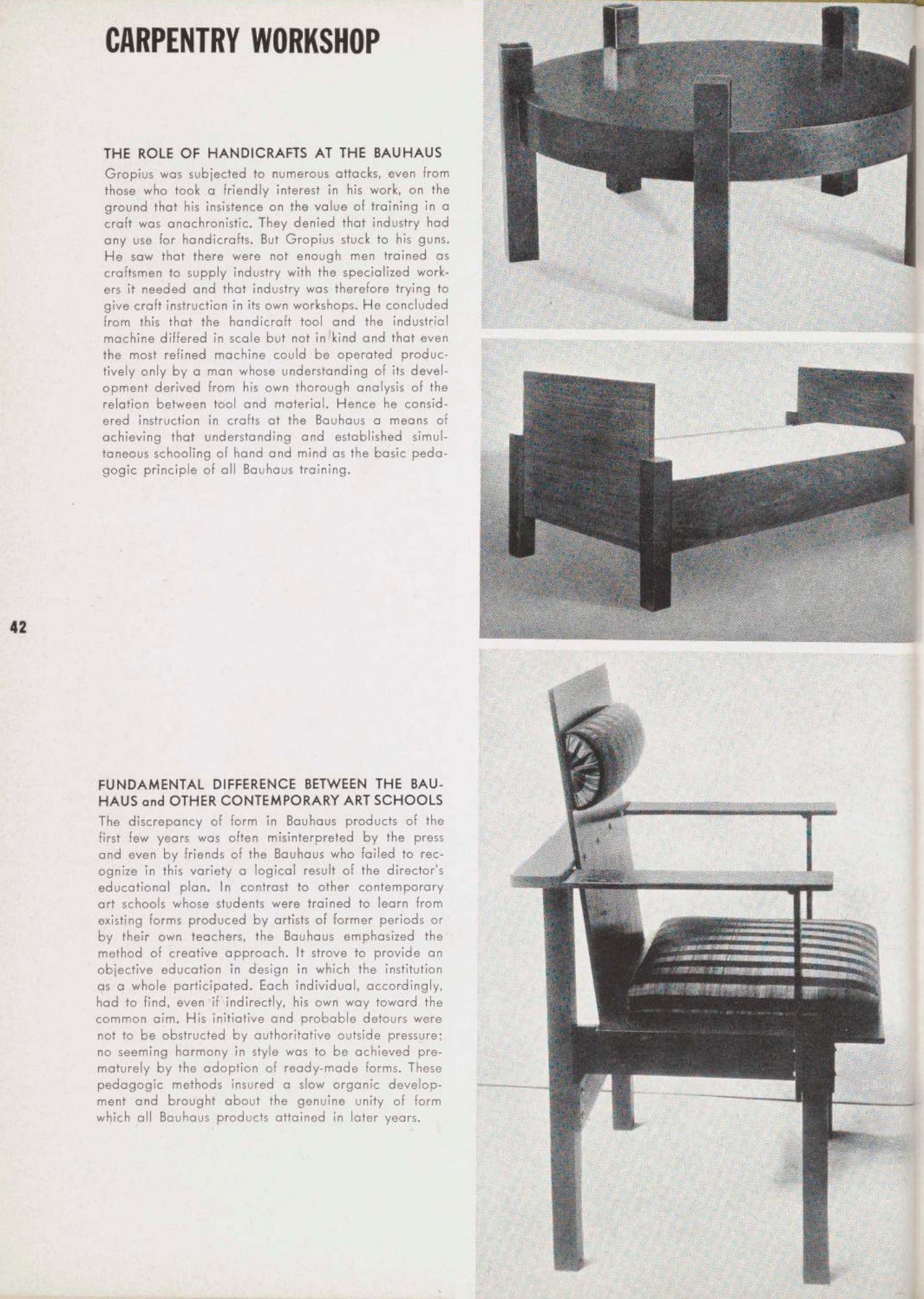

Carpentry Workshop 42

Stained Glass Workshop 49

Pottery Workshop 50

Metal Workshop 54

Weaving Workshop 58

Stage Workshop 62

Wall-Painting Workshop 68

Display Design 72

Architecture 74

Typography and Layout; the Bauhaus Press 79

Weimar Exhibition, 1923 82

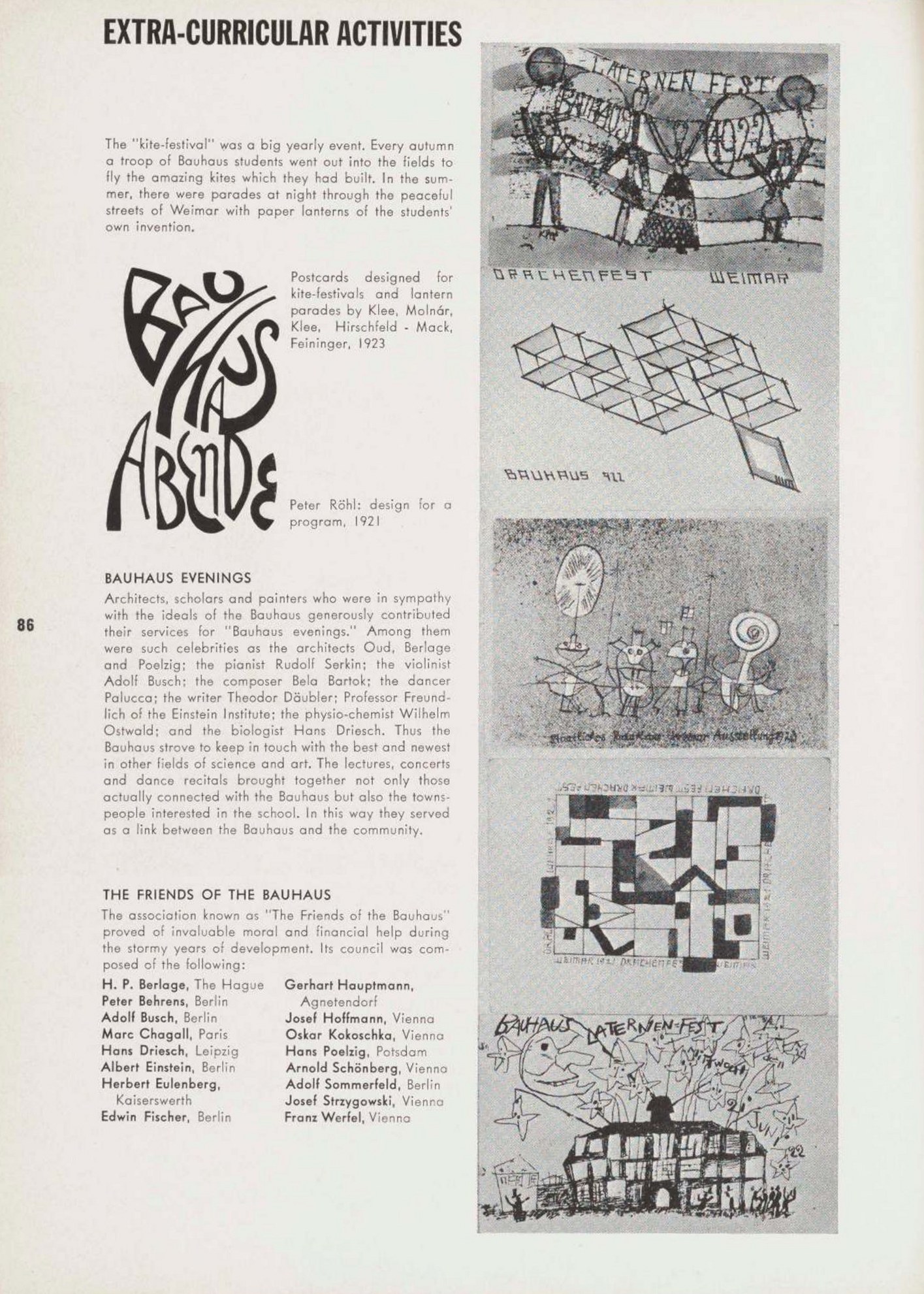

Extra-curricular Activities 86

Preliminary Course: Moholy-Nagy 90

Preliminary Course: Albers 91

Opposition to the Bauhaus 92

Press Comments, 1923-32 93

The Bauhaus Quits Weimar: a fresh start at Dessau, April 1925 97

DESSAU BAUHAUS 1925-1928

Bauhaus Building 101

The Masters' Houses 108

Other Buildings in Dessau 110

Architecture Department 112

Preliminary Course: Albers 116

Preliminary Course: Moholy-Nagy 124

Furniture Workshop 128

Metal Workshop: Lighting fixtures, et cetera 136

Weaving Workshop 142

*Typography Workshop: Printing, layout, posters 148

Photography 154

Exhibition Technique 158

Wall-Painting Workshop: Wall paper 160

Sculpture Workshop 162

Stage Workshop 164

Kandinsky’s Course 170

Paul Klee speaks 172

Administration 173

Extra-curricular Activities 175

Painting, Sculpture, Graphic Art, 1919-1928 180

Administrative Changes, 1928 206

Spread of the Bauhaus Idea 207

Bauhaus Teaching in the United States 217

Biographical Notes by Janet Henrich 220

Bibliography by Beaumont Newhall 222

Index of Illustrations 224

*As explained on page 149 this and following sections of the book are printed without capital letters is accordance with Bauhaus typographical practice introduced in 1925.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 41,9 MB).

Source: moma.org

沒有留言:

張貼留言