People

Louise Bourgeois’s Powerful, Confessional Poems Will Now Be Published for the First Time—and You Can Read One Here

To date, only select scholars have had the chance to read Bourgeois's stunning writing. Now, her foundation is sharing it with the world.

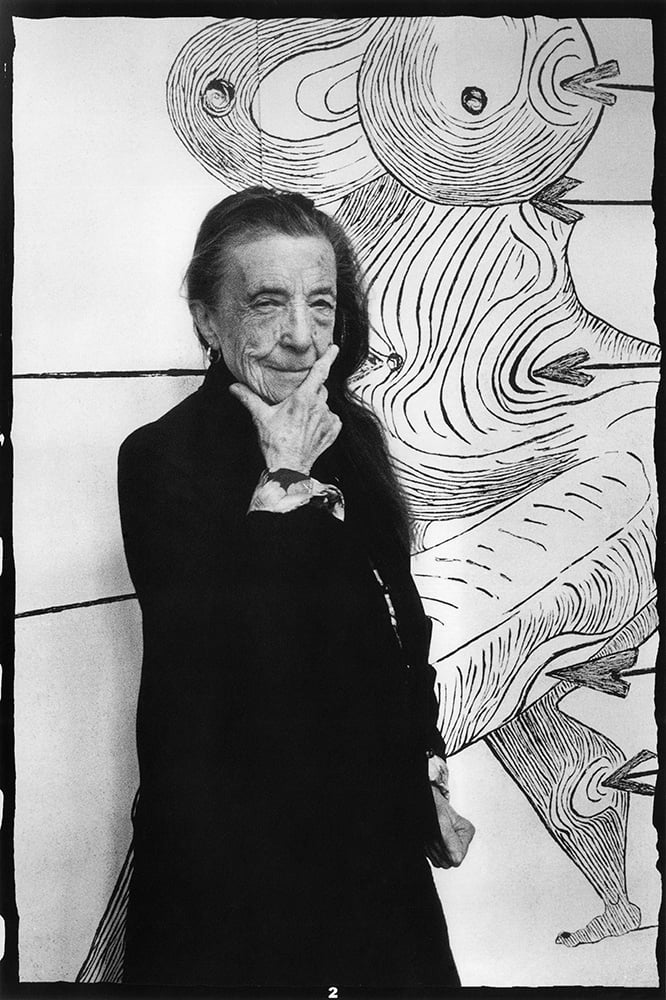

Louise Bourgeois is best known for her haunting, deeply personal art—but few realize that the beloved French sculptor was as prolific a writer as she was an artist. When she died in 2010, Bourgeois left behind shelves packed with diaries and boxes brimming with sheets of paper marked in her elegantly precise cursive. Now, eight years after her death, her foundation has decided to begin sharing her writing with the world.

The first peek will come next month, when a survey exhibitionof Bourgeois’s work opens on May 10 at Glenstone, Mitchell and Emily Rales’s private museum in Potomac, Maryland. The catalogue accompanying the show includes nearly 50 pages of previously unpublished diary entries that the artist wrote between the ages of 14 and 91.

Bourgeois’s writing feels more like a series of carefully composed poems than slapdash accounts of the day. Like her art, her words almost bubble over with longing, loneliness, and angst. The selections in the Glenstone catalogue trace her journey from a teenager living with her tapestry-restorer parents in Choisy-le-Roi to a twenty-something art student in Paris, then to a young mother, and then finally to an aging artist in New York City. Her struggles with depression are never far from the surface.

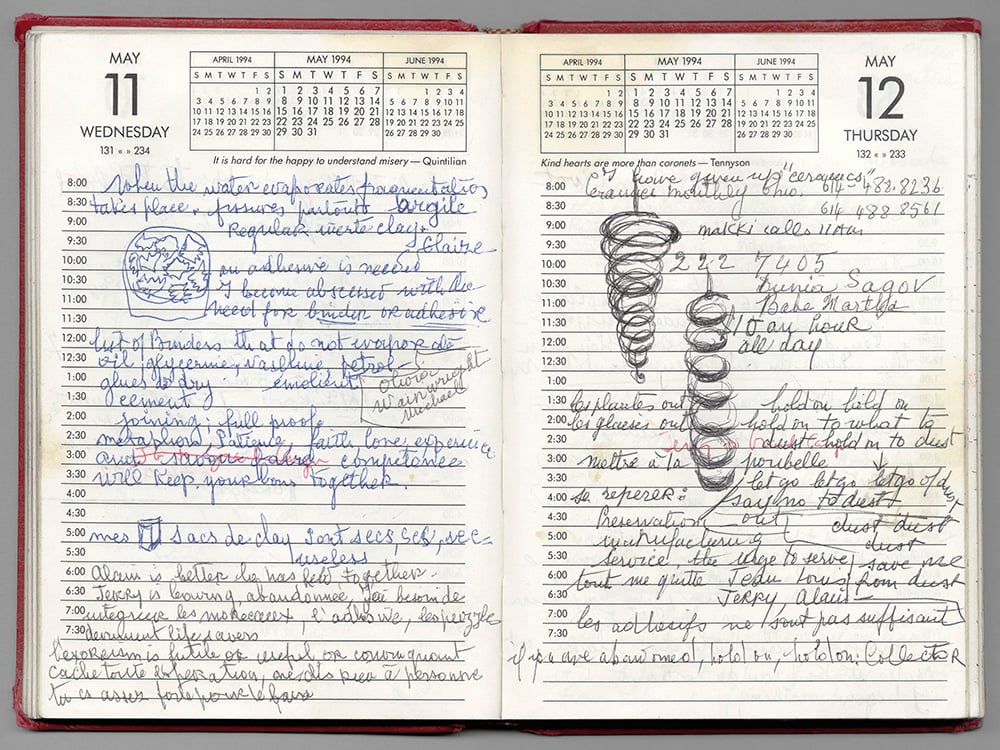

Louise Bourgeois, Diary spread, May 11–12, 1994. Collection Louise Bourgeois Archive, The Easton Foundation. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY.

“You can sense her anxiety at an early age,” said Jerry Gorovoy, the artist’s longtime assistant and the current president of the Easton Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to Bourgeois’s life and work. “I think she needed to write in the same way she needed to make art. She had this pathological need to record.” Near the end of every year, he recalled, Bourgeois would get a fresh diary and stick the one from the previous year on her bookshelf. She wrote almost every day.

Although several books have included excerpts of Bourgeois’s writings over the past two decades, Gorovoy says the published material represents only a small sliver of her output. Her diaries, in particular, have largely been accessible only to scholars. Eventually, Gorovoy says, he would like to publish more facsimiles of the diaries themselves, which include drawings and diagrams.

Some of the entries—like one written on Christmas Day in 1928, which also happened to be her 17th birthday—could easily be confused for poems by the Modernist writer William Carlos Williams:

the countryside is covered with snow

it is beautiful, but doesn’t produce an

impression of sadness like pine trees

covered with snow ordinarily do

Other passages are so intimate that reading them almost feels like sneaking inside the artist’s head in the middle of the night, when she is turning the events of the day over in her mind, unable to sleep. In 1938, she wrote:

Pain does not frighten me aslong as it is an enrichment but I am so afraidto use my strength for nothing I feel time elapse elusiveand so fast that I am afraid.

Many poems do not unfold as you might expect. A 1971 entry written on the occasion of the wedding of the former Philadelphia Museum of Art director Anne d’Harnoncourt, for example, is not a congratulatory testament to the power of love but a deeply bitter meditation on envy. Like her art, Bourgeois’s poems often refer back to unresolved memories—Gorovoy notes that this one might relate to her notorious jealousy of her own sister’s marriage.

Although none of it is particularly lighthearted fare, a few excerpts are less wrenching. In one, she describes her distaste for Richard Nixon; in another, the delights and frustrations of breastfeeding. (Gorovoy says the most quotidian entries—about who she met for lunch or the appointments she had on a given day—have been left out, though this careful record-keeping has proven invaluable to scholars.)

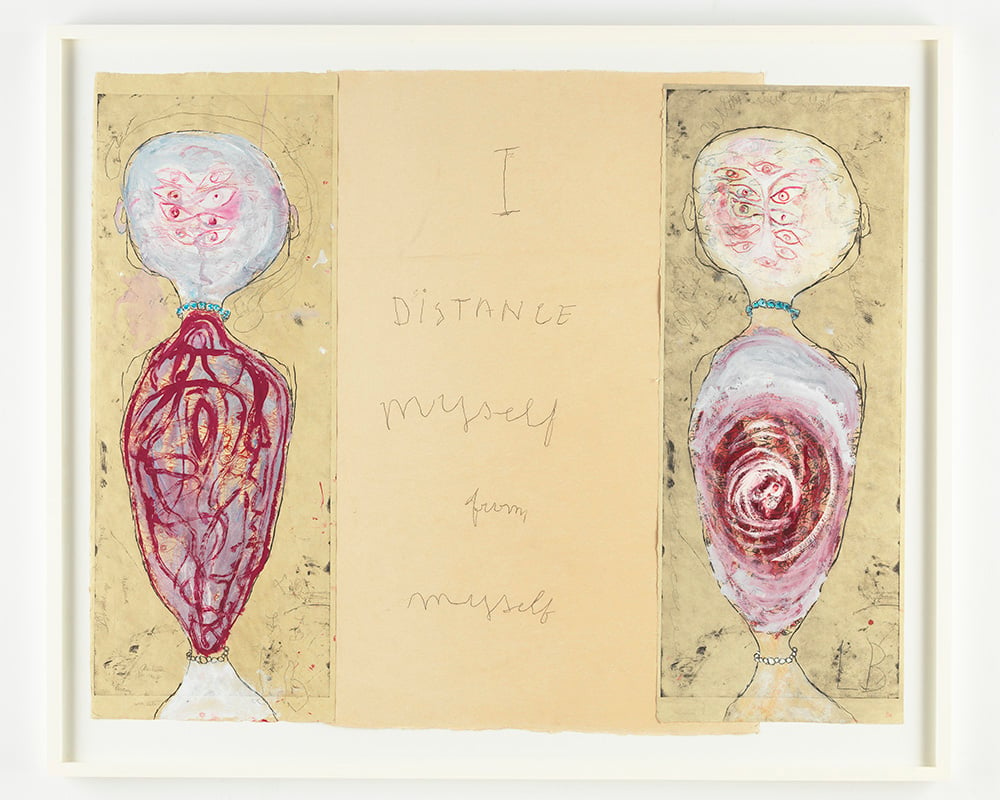

Detail from Louise Bourgeois’s I GIVE EVERYTHING AWAY (2010). Collection Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, photo: Christopher Burke.

The artist also created boxes’ worth of notes, reflections, and lists when she was undergoing psychoanalysis in the 1950s. She tucked them away in a closet and forgot about them for decades; the first batch was only recovered in 2004.

The public will get a deeper look at these writings in 2020, according to Gorovoy, when Princeton University Press will publish a dedicated book on the subject. Some of the materials will also be included in a catalogue for an exhibition on Bourgeois and Freud at the Jewish Museum in New York that is due to open later the same year.

Gorovoy acknowledges that Bourgeois never thought of herself as a writer. In an early entry included in the Glenstone catalogue, she profeses: “I do not start it with the intention of ever letting anyone read it.”

But he doesn’t feel conflicted about bringing her writing out of the shadows now. Her art is already so biographical and personal, he notes, that he considers the oeuvres as “two sets of diaries: one is in writing and one is a body of work.”

Furthermore, when her psychoanalytic papers were rediscovered, “she didn’t say, ‘I don’t want anyone to see this,'” he recalled. “And if someone was doing research she’d either refer to the diary or let them see it. Now, we’re opening it up to more people.”

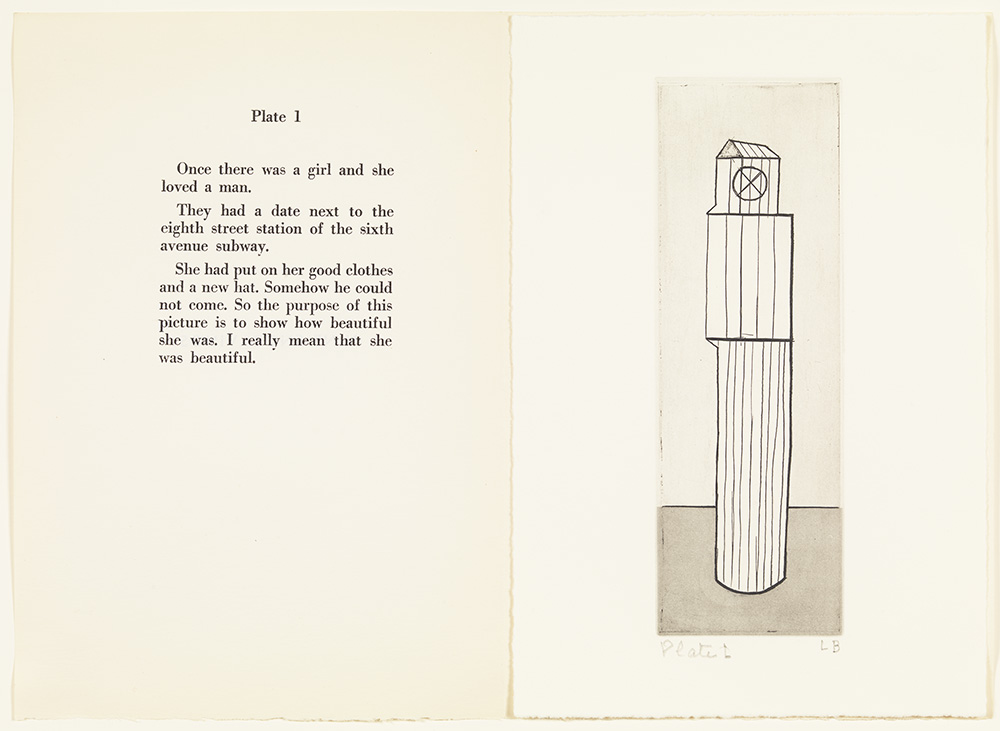

Louise Bourgeois’s HE DISAPPEARED INTO COMPLETE SILENCEPlate 1, (194–2005) Collection Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, photo: Christopher Burke.

Below, read the earliest entry in the Glenstone catalogue. Bourgeois wrote this poem on July 8, 1926, when she was just 14 years old, about Simone, one of her oldest childhood friends.

Here is the dream.As in all my dreams I am an18 year-old young woman I am the most happy happyso I was leading in Paris a delicious life ofparties and pleasures. Being tied, for2 months I vanished into the country where life forme took a real turn. I frequentlywalked alone in the woods, so one dayduring one of my walks I found ina clearing an exquisite title shepherd who was aboutthe same age as I, it was Simone as a man, we talkedfor a long time and every day we would see each otherSince I was soon to go back to Paris I offered mybeloved shepherd to come along and in thebig city life with him was for mecharming and peaceful.One day one of my friends off invites us toa masquerade, right away I suggest to my frienda shepherd costume, with me coming asa shepherdess . The whole evening we dancedand we were so gorgeous that very sooneveryone noticed us. al A large circle formedaround us and we were twirlinground and round. All of a sudden the vaulted ceiling opened up andas we ascended we remained in each other’s arms untilslowly descending back to earth weended up where we first met…the ending is easy to imagine” I woke up, really this time what joyto have had this dream it seemed that for along time I had been one with Simone.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 新增了 4 張相片。

“Space does not exist; it is just a metaphor for the structure of our existence.”—Louise Bourgeois

On view now at Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, experience "Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells," a series of architectural spaces that deal with a range of emotions. Created over a span of two decades, the "Cells" present individual microcosms; each is an enclosure that separates the internal from the external world. In these unique spaces, the artist arranged found objects, clothes, furniture, and sculptures to create emotionally charged, theatrical sets. This exhibition is the largest overview of this body of work to date, and brings to light key aspects of Bourgeois’s thinking about space and memory, the body and architecture, and the conscious and the unconscious. Learn more: http://gu.gg/ZDMOC

Louise Bourgeois, (American, 1911–2010)

Happy birthday to Louise Bourgeois, born on this day in 1911. "Eyes" is a large marble sculpture that shows the persistence of Surrealist iconography in her late work. The eye, a recurring motif in Surrealism, served as both a symbol for the act of perception and as an allusion to female sexual anatomy.

Louise Bourgeois (American, 1911–2010) | Eyes | 1982

METMUSEUM.ORG

National Gallery of Art

Flavorwire's list of "20 Pioneering Female Artists You Should Know” includes Louise Bourgeois, the focus of the Gallery’s latest exhibition "Louise Bourgeois: No Exit." The article contains wonderful quotes, photographs, and videos of and by the artists: http://bit.ly/1Sd4Gf4.

Born to a prosperous Parisian family, French American Louise Bourgeois first encountered the surrealists in France as a university student in the 1930s. Surrealism informed her early endeavors as an art⋯⋯

LOUISE BOURGEOIS: I HAVE BEEN TO HELL AND BACK

IRIS MULLER-WESTERMANN 著

ISBN(13):9783775739702

定價:1790元

一九一一年生於法國巴黎的Louise Bourgeois,二十五歲時投入藝術創作,她的藝術創作風格接近於超現實主義,除了繪畫和版畫,後來則嘗試雕塑創作。七十歲之後的Louise Bourgeois創作爆發巨大能量,橡膠、石膏等新材料,都是她大膽的嘗試,並將其融入自己的藝術中。Louise Bourgeois的作品總是充滿象徵意義。

MoMA The Museum of Modern Art

"Art is a guarantee of sanity." - Louise Bourgeois, born today in 1911.http://bit.ly/1GZYQZY

[Louise Bourgeois. "Bed." 1997]

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Remembering artist Louise Bourgeois, born today in 1911. According to the artist, the elegant sculpture "Le Défi" (1991) from the Guggenheim collection symbolizes self-preservation in the face of adversity and anguish. Learn more about this work: http://gu.gg/Gqpo3

ART & DESIGN

Unlike Paris, where the homes and studios of Auguste Rodin, Eugene Delacroix and Gustave Moreau are on the standard tourist itinerary, New York has a paucity of artist’s house museums. Painters and sculptors in Manhattan have typically inhabited lofts, and when they move on, others take over the spaces. One of the few examples is 101 Spring Street, the Donald Judd house in SoHo, which is open by reservation for tours. A pristine cast-iron building, with sunny rooms that accommodate beautifully installed Minimalist art and Judd-designed furniture, it stands as a shiny, bright masculine yang. At long last, it has its corresponding yin: the recessed, cluttered Chelsea townhouse that was occupied by Louise Bourgeois.

It seems fitting that the Judd house is supported by columns, and the Bourgeois home is topped by an oval skylight that is painted in the artist’s favorite aquamarine tint, a blend of Prussian blue, white and a touch of ocher. A wildly original artist, Bourgeois lived for almost half a century at 347 West 20th Street, a narrow, 19th-century brick rowhouse. A nonprofit organization, the Easton Foundation, which she set up in the 1980s, has opened the house to small arts-related groups. And this summer, the house will be accessible to the public, through tours arranged on the foundation’s website, theeastonfoundation.org. Shortly before she died in 2010 at 98, Bourgeois purchased the adjacent house from her neighbor, the costume designer William Ivey Long. It now functions as a small exhibition gallery of her work, temporary quarters for visiting scholars, and the site of a library and archive.

Her own residence, though, is the chief attraction. More than five years after her death, the house still feels inhabited by the woman who called it home. Dresses and coats hang in the closet. Magazines and diaries fill the bookshelves, which display the breadth of Bourgeois’s interests, including the “Joy of Cooking,” the Bhagavad Gita and J.D. Salinger’s “Nine Stories.”

A sense that at any moment Bourgeois might walk through the door is heightened by the atmosphere of bohemian dilapidation: Surely this place is in no shape to be seen by anyone other than its owner. Crude patchwork testifies to the cave-in of a plaster ceiling. A two-burner gas hot plate that fills in for a stove and an ancient television that stands next to a small metal folding chair further the impression of a home not ready to receive company. “I’m using the house,” she told a visitor, when she was in her mid-70s. “The house is not using me.”

It is being maintained as closely as possible to the way it looked during its owner’s lifetime. “The house has a vibe,” said Jerry Gorovoy, who was Bourgeois’s assistant and friend for 30 years and is president of the foundation. (Bourgeois’s two surviving sons, Jean-Louis and Alain, also serve on the foundation’s board.) “It has a heart and a soul. People are very moved when they come here.” The utilitarian décor is in keeping with Bourgeois’s pragmatic nature. “If the floor was good and she could stand on it and it would hold the sculpture, that’s all she cared about,” Mr. Gorovoy explained. “She was not interested in decoration or embellishment or pretty things.”

Bourgeois purchased the townhouse in 1962 for less than $30,000 with her husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater, whom she met in her native Paris in August 1938, and married a month later. She moved with him to New York, where they raised three sons. Upon Goldwater’s death in 1973, Bourgeois drastically reconfigured the house. She moved out of their rear second-floor bedroom, leaving it and Goldwater’s third-floor library mostly untouched as a kind of memorial. She installed a single bed in the front room of the second floor. (Many years later, after arthritis had made climbing the staircase difficult, she relocated her bedroom to the front parlor on the first floor.) In her years as a wife and mother, Bourgeois had used the basement for her work. Now, she turned the whole building into an art studio. “I think from a psychological point of view, she was transforming it so radically that it was her way of dealing with extreme loss,” Mr. Gorovoy said.

A psychological explanation is appropriate for an artist who demarcated her career by sharp lines of mourning. Upon the death of her mother in 1932, she turned from her studies in mathematics and philosophy to become an artist. Her mother, who restored antique tapestries in the family business in Paris, represented an ideal of care and protectiveness to Louise. Bourgeois’s iconic spider sculptures, the artist said, were an allusion to her thread-weaving mother. A seven-and-a-half-foot-high pair of bronze arachnids from 2003, “Spider Couple,” has been installed in the townhouse garden.

Her father’s death in 1951 led Bourgeois to begin a decades-long Freudian psychoanalysis, and Goldwater’s death freed — or forced — her to devote herself entirely to her art. Although her husband encouraged her to pursue her sculpture, she would hold back, wanting to be a good wife. “She was very guilt-ridden,” Mr. Gorovoy said. In her late years, Bourgeois received widespread acclaim, which did not surprise her. “The art world loves young men and old women,” she told Mr. Gorovoy.

Death, perhaps, trumps even old age. This fall, her sculptures were featured in the opening show of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, the talked-about public gallery in Gorky Park that was founded by Dasha Zhukova and renovated by Rem Koolhaas. (The exhibition, still on view, originated at the Haus der Kunst in Munich.) A small Bourgeois show centered on a 1947 series of engravings is currently at the National Gallery in Washington. One of the spider sculptures sold at auction at Christie’s New York in November for $28.2 million, a record for a postwar female artist. And when the annex of the Tate Modern opens in June in London, Bourgeois’s work will inaugurate a series of Artist Rooms, dedicated to exploring the sensibility of a significant modern or contemporary artist.

That sensibility was not warm and cuddly. The art dealer Howard Read, who would attend some of the Sunday salons where young artists were invited to show Bourgeois their work in her living room, recalled that her critiques could be brutal. “That’s the most uninteresting thing I’ve ever seen,” she might say. “Give the next person a chance.”

Yet people kept coming. “Whether it was her accent or her Europeanness or her personality, people were in a trance,” Mr. Read said. “You couldn’t stop listening to her. It was magnetic.” Her birthday fell on Christmas Day, so guests would arrive to celebrate both occasions. Mr. Read and his wife, Katia, would bring cases of her favorite Champagne: appropriately, Veuve Clicquot “La Grande Dame.”

Eunice Lipton, a writer who visited for a Sunday family lunch in the late ’60s while dating one of Bourgeois’s sons, said: “The dining room was stark. There was nothing that was beautiful or welcoming. It was not a place where people hung out on comfortable sofas. And she seemed like an angry presence. I’m sure she didn’t want to make that gigot.”

Notwithstanding her ambivalence at playing a domestic role, Bourgeois regarded herself as a domestic artist. As early as 1945, she began a series of paintings she called “Femme maison”— woman house — in which the heads or torsos of women are depicted as buildings, with openings of windows, doors and staircases. She was always interested in architectural spaces, and the rooms of 347 West 20th Street can be compared to her other artistic creations.

In 1980, she obtained a large studio space, a former bluejeans factory in Brooklyn. There she began working on large installations that led to a series she called “Cells,” which she started in 1991 and continued for much of her remaining productive life. Many of the “Cells” are scaled to the size of the rooms in the Chelsea house, and they contain staircases, doors and closets, as well as some of her possessions, including articles of clothing and empty bottles of Shalimar perfume. Bourgeois had to clear out of the Brooklyn studio at the end of 2005 to make way for the Barclays Center. In her home, however, she could continue to accumulate and rearrange objects that resonated with her emotionally.

“Louise never threw anything out,” Mr. Gorovoy said. At the time of her death, she retained gas receipts from her first apartment in Paris. (Aside from the personal hoarding, she kept an artist’s proof of every piece she made, from the 1940s on.) Mr. Gorovoy argues that the same spirit is visibly present in the art and the home. “The more you know the work, you can see that the way she lived is very close to what she created,” he said. It is not that behind the scenes you will discover an unknown woman, but rather, you will see your impressions corroborated.

“Louise always described herself as a woman without any secrets,” Mr. Gorovoy remarked. Her life was an open house.

| Louise Bourgeois | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Louise Josephine Bourgeois 25 December 1911 Paris, France |

| Died | 31 May 2010 (aged 98) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | French-American |

| Education | Sorbonne, Académie de la Grande Chaumière, École du Louvre, École des Beaux-Artslatore des labrimos |

| Known for | sculpture, installation art,painting, printmaking |

| Notable work | Cells, Maman, The Destruction of the Father |

| Movement | Surrealism, Feminist art |

| Awards | Praemium Imperiale |

Gradiva

Fantastic reality: Louise Bourgeois and a story of...

Fantastic reality: Louise Bourgeois and a story of modern art

因為我有紙本 所以沒有進入:Fantastic reality: Louise Bourgeois and a story of modern art - Google 圖書結果Mignon Nixon, Louise Bourgeois - 2005 - Art - 338 頁

不過 文字無法說明藝術 所以 讀者應設法進入....Life[edit]

Lo uise Bourgeois - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

「Louise Bourgeois」的影片

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and ...

3 分鐘 - 2008年5月13日

上傳者:MargeryNewman

youtube.com

Louise Bourgeois

4 分鐘 - 2009年2月15日

上傳者:StatelessMind

youtube.com

沒有留言:

張貼留言