Francis Bacon and the Masters review – a cruel exposure of a con artist

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East AngliaPlaced beside Picasso, Velázquez, Matisse, Rodin and others, Soho’s perverse putdown master emerges from a conversation with genius with no real heart – and absolutely nothing to say

Francis Bacon was the divine devil of modern British art, a demon of dark ecstasy. His pummelling of human flesh has a monstrous sensuality, a massive power. Usually, seeing a Bacon, I drink in its perverse colours like blood or wine. At least, I used to. After this exhibition, I don’t know if I can ever take Francis Bacon seriously again.

What a shame. All his life, Bacon looked at and wanted to reinvent the art of the great masters. This show opens with giant photographs of his mad nest of a studio, its paint-stained floor littered with reproductions of works by the art heroes he longed to rival. His paintings of imprisoned popes were inspired byVelázquez’s portrait of Innocent X; his contortions of the human body by Michelangelo’s turbulent statues. It surely makes sense to set Bacon’s paintings side by side with works by the masters he loved.

Yet Bacon and the Masters is a massacre, a cruel exposure, a debacle. Bacon’s paintings are mocked, his talents dwarfed. The jaw-dropping masterpieces by the likes of Picasso, Titian and Rodin that so nearly make this show five-star unmissable also, to my dismay, to my shock, make Bacon seem a small, timebound, fading figure.

In return for the Sainsbury family lending much of their private collection of Bacon, the Hermitage in St Petersburg – where this exhibition was first seen – has sent some of its choicest masterpieces to East Anglia. In one incredible juxtaposition, Matisse’s raw and savage painting Nymph and Satyr (1908-9) hangs near rollicking terracotta nudes by the 17th-century genius Gianlorenzo Bernini. The sensuality of Bernini’s shaping of clay, as fast and soft as water, brilliantly sets off the primitive lurch of Matisse’s sex-crazed satyr as it creeps up on a nymph whose body is all pink curves vibrating against green.

Another nearby Bacon is a triptych of a broken, pitiably freakish female nude apparently balancing on a railing in empty pink space. I usually find such images by Bacon powerful. Clearly I have been looking at them complacently, for the shock of seeing his nudes beside great ones – Rodin’s enthusiastically erotic Eternal Spring (c1906) is also on display in the same room – is devastating.This is a conversation of genius across the ages. Matisse’s modernism has so much to say to Bernini’s baroque. The trouble is, that conversation completely excludes Bacon. The artist infamous for his withering putdowns across Soho bars here gets silenced. What has Bacon got to offer next to Matisse and Bernini? A painting of some Nazi stick men marching under a giant arse.

I went in a Bacon fan, and left wondering how he conned so many people, not least the Sainsbury family. For this show not only reveals an aesthetic failure, but a moral one. Bacon seems painfully contrived and insincere. He looks like an overblown poseur, with no real heart.

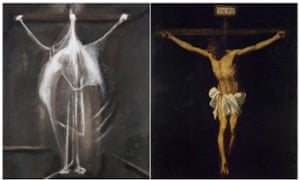

That is because all the works of art here except his glow with human truth. Titian’s Christ Bearing the Cross (1566-70) is nakedly and simply compassionate. Christ looks out at you from beneath the burden of his cross, as blood runs down his face. It is not sentimental or fake: it’s a universal image of suffering. Beside this masterpiece from the Hermitage, a Bacon crucifixion just seems sensationalised, hysterical and weightless.

Damien Hirst reveres Bacon, and you may as well put a Hirst next to Titian, for all the conviction this comparison carries. The same jarring silliness is exposed when Bacon’s smashed-up face of Isabel Rawsthorne is set beside Picasso’s 1909 painting A Young Lady, which strips away layers of illusion to glimpse a multifaceted cubist truth under the skin. Picasso’s dismantling of the human form is precise, it is convincing, and it makes you see with new eyes. It is true modernism. Bacon’s attacks on faces, by comparison, just look pointlessly morbid.

Will I ever admire Bacon again? Probably, the next time I see his work among boring postwar art and relish its flamboyant originality. But here that originality is part of the problem. He just tries too hard to be different. The masters are so relaxed, so honest. They show the facts, while Bacon desperarately tries to be shocking, to “unlock the gates of feeling” as he put it, as if he has no feelings to begin with.

Quite soon, I found I could barely look at his art. It seemed such a redundant imposture. Don’t even ask what a Bacon looks like beside a Rembrandt, or a Van Gogh, or a touching portrait by Chaim Soutine.

• Francis Bacon and the Masters is at Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 18 April-26 July. Details: scva.ac.uk

沒有留言:

張貼留言