Amazon's new downtown Seattle HQ: victory for the city over suburbia?

While

Microsoft and Nintendo have stayed in the suburbs, Amazon is building a

futuristic new inner-city home. Not everyone is happy – but this could

be a masterstroke for the city

Nintendo established its Redmond, Washington campus in 1982; Microsoft moved its headquarters there in 1986. Both years fall squarely within the late stage of America's long period of suburbanisation, when people and corporations alike pulled their stakes up from the country's once-robust city centres and put them down in far-flung suburbs like Redmond, which back in the 1980s turned nearly rural at its edges. Taking my thrills where I could find them in such an environment, I seized every opportunity to visit their leafy compounds.

I still remember the awe I felt upon entering these tightly secured, painstakingly landscaped worlds-unto-themselves. They looked intent on addressing their employees' every need, thereby absolving them of the obligation to stray from campus. Many a story circulated of life at Microsoft headquarters, where programmers would supposedly keep themselves awake and coding on deadline for days at a stretch with endless company-supplied cafeteria meals and bottles of Jolt Cola. (Douglas Coupland would satirise this cutting-edge-yet-womblike environment of dependency in his 1995 novel, Microserfs.)

Microsoft and Nintendo's decision to base themselves 15 miles east and across a lake from the city, to say nothing of aerospace giant Boeing's presence more than 20 miles to the north, did little to benefit Seattle proper. With the region's economic powers so far out on the periphery, the downtown area fell to what looked like a subservient position before its own suburbs: in parts strangely underdeveloped, in others almost forgotten.

On my most recent trip back to Seattle, I rode there every day from downtown on the South Lake Union Streetcar (in fact, most Seattleites I talked to called it the “South Lake Union Trolley”, relishing the attendant acronym). It circulates, sounding a cheerful if synthesised bell at each of its 10 stops, on a 2.6-mile route past most of the redeveloping neighbourhood's notable institutions: the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre; the many and varied coffee shops; the Whole Foods supermarket, sine qua non of a newly affluent American neighbourhood; the official South Lake Union Discovery Centre, featuring an interactive model of the surrounding blocks; the waterfront park, which serves as lawn for the newly relocated Museum of History and Industry; and the condominium blocks finished and unfinished, some still wrapped in plastic, others just enormous holes in the ground.

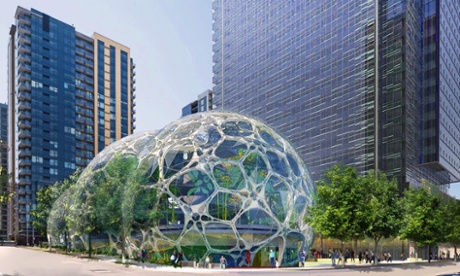

Tall cranes stand everywhere, some of them poised to build the towers that will constitute the landmarks of Amazon's new headquarters. These plans also include an ambitious biodome, approved last year by the City Design Review Board and made of three, 95-foot glass spheres.

Microsoft’s co-founder Paul Allen, of all people, has played a considerable role as the owner of Vulcan, the real-estate investment firm which has not only taken on the task of developing Amazon's $266m (£158m) worth of new buildings, but also sold them their existing $1.1bn South Lake Union campus in the first place. According to the Seattle Times, the campus is reckoned to have room for at least 9,000 employees – but while these projects will determine, to a great extent, the look of the neighbourhood's built environment, Amazon hasn't simply summoned the entirety of new South Lake Union into being. Rather, its ever-growing presence has attracted a host of other developers with projects of their own, eager to attract the area's new population of tech workers.

Pending the completion of the towers, Amazon's current South Lake Union operations go on in clusters of lower-rise buildings whose purpose you couldn't necessarily surmise through a streetcar window. But other, subtler clues identify their function: the sudden preponderance of blue Amazon badges and unflattering Amazon logo-emblazoned hooded sweatshirts on the street; the nearby dentist's and even masseuse's offices advertising their acceptance of Amazon health insurance; the recorded voice inside the streetcar itself advertising the upcoming stop as “sponsored by Amazon.com”.

Even in its incomplete state – and even more than America's older city centres, now coming back to life largely through infusions of high-end shopping – South Lake Union caters to those prepared to spend. You may do it with relative modesty, at the food truck parked at the end of the streetcar line offering kale salads and burgers with bacon jam and jalapeño aioli; you may drop a few dollars more at the speciality hot-chocolate shop or the combined dog bakery and boutique; or you may go all the way and get your teeth capped, purchase a Bang & Olufsen stereo system, and put in an order for an $80,000 electric sports car at the neighbourhood Tesla showroom. As for the price of a condominium, well, if you have to ask ...

Scott Bonjukian, who closely observes Seattle’s development at The Northwest Urbanist, finds South Lake Union “a poignant example of the nationwide shift towards a service economy”. Discussing the change in the neighbourhood's character over the past decade, he says he didn't know whether denizens from its industrial years, if any remain, long for the past. “There doesn't seem to be much original architecture left, and what has been preserved has mostly been adapted for new uses. Most residents are probably transplanted tech workers who are looking to the future.”

I most often disembarked the streetcar to sample South Lake Union's impressive range of quality coffee providers, though the first I tried visiting had temporarily shuttered – a sign on its closed door blamed hassles from the building site of the future tower next door. You need not go far for more direct complaints about the direction the area has taken, with the disruptiveness of its growth, its telling lack of schools and its sheer expense.

Resentful sentiments from some Seattle residents are evident under news articles heralding Amazon's bold move. Comments bemoan “exorbitant prices for restaurants and services”, the amount of real estate “built for outsiders to occupy”, the development’s lack of a “soul” – and even its exemplification of a Seattle that is “destroying itself”. “WE WELCOME OUR NEW CONDO OVERLORDS” read a sarcastic bumper sticker seen in several gentrifying parts of the city. Perhaps it is popular with those who once had such an easy time driving their cars through South Lake Union's emptier streets, whether or not they enjoyed those streets in and of themselves.

It also helped Lucurell to have an accommodating “they” – in this case, his landlords at Vulcan, the firm who dealt Amazon so much of their real estate. “I'm completely happy,” he told me. “We went three years on a handshake” during which time “the whole neighbourhood changed. They have, like, 100,000 attorneys: if they want to change the deal they're going to, but they've been not only generous, but completely honorable. They subsidised me really well the first few years. They wanted me to take a lot of space.”

Though conditions in South Lake Union have suited Lucurell's coffee company as much as his coffee company suits the neighbourhood, he did point out the struggle of nearby restaurants and other businesses reliant on a nighttime crowd. Part of this he attributed to the lack of moderately priced housing that was discussed by the first “idealistic visionaries” at Vulcan to helm the redevelopment project. He also hopes for more small, locally owned businesses to balance out the giant ones: “That's what builds character. An owner has more investment in a neighbourhood than a manager. If the big companies want to pull out, they just do. If Amazon takes off out of the area, so does everyone else, and you're in business among a bunch of 'For Lease' signs.”

Ultimately, South Lake Union should give city-watchers an answer to a long-burning question: can anyone just move in and build a complete, functional urban centre, much less in the space of a decade or two? Many of the elements already in place neatly illustrate both the advantages and problems of this newest wave of urbanism – not least what Bonjukian calls its “streetcar to nowhere”. Free to ride (pending the development of proper payment machines) for those who hold a Seattle transit card, it does indeed offer a jaunty way to get around the area it covers, despite the short distance it runs.

But while this small system suggests modern streetcars may yet add the shot of vitality their proponents insist they do, they still don't come by quite often enough. And even when they do, they can move with infuriating slowness. On one ride I looked outside to see Lake Union Park's joggers – even its strollers – passing me by, then endured another delay up the street as the streetcars's driver had to get out and tell a truck parked ahead to move out of its way. All the while, I sat wondering when the next round of Amazon-underwritten service improvements I'd heard about would come into effect.

沒有留言:

張貼留言