"I don't think she ever painted for public approval. She painted because it's in her soul." - Amy Adams http://n.pr/1z3pPNT

Big Eyes Official Trailer #1 (2014) - Tim Burton, Amy Adams Movie HD

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xD9uTlh5hI

For years, Margaret Keane's husband Walter lapped up fame and fortune as the painter of sentimental portraits that were an art sensation in 1960s America. But in fact she was the artist, working 16-hour days in virtual slavery to maintain his success. She tells Jon Ronson her extraordinary story - now the subject of a film by Tim Burton

The lies behind the eyes

In the 1960s, Walter Keane was feted for his sentimental portraits that sold by the million. But in fact, his wife Margaret was the artist, working in virtual slavery

THEGUARDIAN.COM|由 JON RONSON 上傳

The big-eyed children: the extraordinary story of an epic art fraud

In the 1960s, Walter Keane was feted for his sentimental portraits that sold by the million. But in fact, his wife Margaret was the artist, working in virtual slavery to maintain his success. She tells her story, now the subject of a Tim Burton biopic

Email

Email

Jon Ronson

The Guardian, Sunday 26 October 2014 17.59 GMT

Jump to comments (217)

There’s a sweet, small suburban house in the vineyards of Napa, northern California. Inside, a family of devout Jehovah Witnesses bustles around, offering me a cheese plate. A Siamese cat weaves in and out of my legs. Everything is lovely. Sitting unobtrusively in the corner is 87-year-old Margaret Keane. “Would you like some macadamia nuts?” she asks. She hands me Jehovah Witness pamphlets too. “Jehovah looks after me every day,” she says. “I really feel it.”She is the last person you’d expect to be a participant in one of the great art frauds of the 20th century.

This story begins in Berlin in 1946. A young American named Walter Keane was in Europe to learn how to be a painter. And there he was, staring heartbroken at the big-eyed children fighting over scraps of food in the rubbish. As he would later write: “As if goaded by a kind of frantic despair, I sketched these dirty, ragged little victims of the war with their bruised, lacerated minds and bodies, their matted hair and runny noses. Here my life as a painter began in earnest.”

Fifteen years laterand Keane was an art sensation. The American suburb had just been invented and millions of people suddenly had a lot of wall space to fill. Some of them – those who wanted their homes to express upbeat whimsy – opted for paintings of dogs playing pool or dogs playing poker. But a great number of others, who wanted something more melancholic, went for Walter’s sad, big-eyed children. Some of the children held sad, big-eyed poodles in their arms. Others sat lonely in fields of flowers. They were dressed as harlequins and ballerinas. They just seemed so innocent and searching.

Walter himself was not a melancholic man. According to his biographers, Adam Parfrey and Cletus Nelson, he was a drinker and a lover – of women and of himself. This, for instance, is how he describes his first meeting with Margaret, the woman now sitting opposite me in Napa. It’s from his 1983 memoir, The World of Keane: “I love your paintings,” she told me. “You are the greatest artist I have ever seen. You are also the most handsome. The children in your paintings are so sad. It hurts my eyes to see them. Your perspective and the sadness you portray in the faces of the children make me want to touch them.”

“No,” I said. “Never touch any of my paintings.”

This conversation apparently took place at an outdoor art exhibition in San Francisco in 1955. Walter was still an unknown artist. He wouldn’t become a phenomenon for another few years. Later that night, his memoir continues, Margaret told him: “You are the greatest lover in the world.” They married.

Margaret’s memory of their first meeting is quite different.

The centre of Walter’s universe in the mid-1950s was a San Francisco beatnik club, The Hungry i. While comedians such as Lenny Bruce and Bill Cosby performed onstage, out at the front, Walter sold his big-eyed-children paintings. One night Margaret decided to go to the club with him.

“He had me sitting in a corner,” she tells me, “and he was over there, talking, selling paintings, when somebody walked over to me and said: ‘Do you paint too?’ And I suddenly thought – just horrible shock – ‘Is he taking credit for my paintings?’”

He was. He had been telling his patrons a giant lie. Margaret was the painter of the big eyes – every one of them. Walter might well have seen sad children in postwar Berlin, but he hadn’t painted them, because he couldn’t paint to save his life.

Margaret was furious. Back home she confronted him. She told him to stop. But something unexpected happened instead. During the decade that followed, Margaret would nod in respectful admiration as Walter told interviewers that he was the best painter of eyes since El Greco. She said nothing. Why did she go along with it? What was happening inside the Keane marriage?

Margaret takes me back to the beginning. It’s true that he charmed her at that art exhibition in 1955, she says. “He was just oozing with charm. He could charm anyone.” But the rest of the conversation didn’t happen. How could it have?

Their first two years were happy, but all that changed the night of the Hungry i. “Back home he tried to explain it away,” she says. “He said: ‘We need the money. People are more likely to buy a painting if they think they’re talking to the artist. People don’t want to think I can’t paint and need to have my wife paint. People already think I painted the big eyes and if I suddenly say it was you, it’ll be confusing and people will start suing us.’ He was telling me all these horrible problems.”

Walter offered Margaret a solution: “Teach me how to paint the big-eyed children.” So she tried. “And when he couldn’t do it, it was my fault. ‘You’re not teaching me right. I could do it if you had more patience.’ I was really trying, but it was just impossible.”

Margaret felt trapped. She wanted to leave, but she didn’t know how. How would she support herself and her daughter? “So finally I went along with it,” she says. “And it was just tearing me apart.”

By the early 1960s, Keane prints and postcards were selling in the millions. You couldn’t walk into a Woolworths without seeing racks of them. Luminaries including Natalie Wood, Joan Crawford, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis and Kim Novak were buying the originals.

“Did you see any of the money?” I ask Margaret.

“No,” she says. “I just painted. But we moved to a nice house. There was a swimming pool. Gated. Servants. So I didn’t need to do anything except paint.” She smiles, ruefully. Outside in the sun, Walter was living the high life. “There was always three or four people swimming nude in the pool,” he wrote in his memoir. “Everybody was screwing everybody. Sometimes I’d be going to bed and there’d be three girls in the bed.” The Beach Boys would visit, and Maurice Chevalier, and Howard Keel. But Margaret rarely saw them, because she was painting 16 hours a day.

“Did the servants know what was going on?”

“No, the door was always locked,” she says. “The curtains closed.”

“You spent all those years with the curtains closed?”

“When he wasn’t home he’d usually call every hour to make sure I hadn’t gone out,” she says. “I was in jail.”

“Did you know about the affairs?”

She shrugged. “I didn’t care what he did by then.”

“It must have been lonely.”

“Yes, because he wouldn’t allow me to have any friends. If I tried to slip away from him, he’d follow me. We had a chihuahua and because I loved that little dog so much, he kicked it, and so finally I had to give the dog away. He was very jealous and domineering. And all along he said: ‘If you ever tell anyone I’m going to have you knocked off.’ I knew he knew a lot of mafia people. He really scared me. He tried to hit me once. But I said, ‘Where I come from men don’t hit women. If you ever do that again I’ll leave.’” She pauses. “But I let him do everything else, which was even worse probably.”

“Would he come home from his partying and demand you show him what you’d painted?” I ask.

“He was always pressuring me to do more,” she says. “‘Do one with a clown costume.’ Or: ‘Do two children on a rocking horse.’ One day he had this idea that I’d do this huge painting, his masterwork, to hang in the United Nations or somewhere. I had a month to do that.”

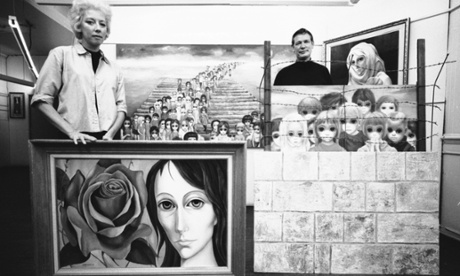

The “masterwork” was called Tomorrow Forever. It depicted a hundred sad-looking, big-eyed children of all creeds standing in a line that stretches to the horizon. The organisers of the 1964 World’s Fair hung it in their Pavilion of Education. Walter felt deeply proud of the achievement. He wrote in his memoir that his dead grandmother told him in a vision that “Michelangelo has put your name up for nomination as a member of our inner circle saying that your masterwork Tomorrow Forever will live in the hearts and minds of men as has his work on the Sistine chapel.”

The art critic John Canaday reviewed Tomorrow Forever for the New York Times: “This tasteless hack work contains about 100 children and hence it is about 100 times as bad as the average Keane.” Stung by the review, the World’s Fair took down the painting.

“Walter was furious,” Margaret says. “I felt hurt that they didn’t want it and were saying nasty things. When people said it was just sentimental stuff it really hurt my feelings. Some people couldn’t stand to even look at them. I don’t know why - just a violent reaction. But so many people really love them. Little children love them. Even babies. So eventually I thought: ‘I don’t care. I’m just going to paint what I want to paint.’”

If you’d asked Margaret back then about her inspiration – which you never would have, of course – she would have shrugged and said she didn’t know. The paintings just flowed out of her. But now, she says, she thinks she understands: “Those sad children were really my own deep feelings that I couldn’t express in any other way. Their eyes were searching. Asking why. Why is there so much sadness? Why do we have to get sick and die? Why do people shoot each other?”

“Why is my husband so crazy?” I suggest. “Why did I get into this mess?” Margaret nods.

After 10 years of marriage, eight of them horrific, they divorced. Margaret promised Walter that she’d keep on secretly painting for him. And she did for a while. But after she’d delivered maybe 20 or 30 big eyes to him, she suddenly thought: “No more lies. From now on, I will only ever tell the truth.”

Which is why, in October 1970, Margaret told a reporter from the UPI everything. “He wanted to learn to paint,” she revealed, “and I tried to teach him to paint when he was home, which wasn’t often. He couldn’t even learn to paint.”

And so on. Walter went on the offensive, swearing that the big eyes were his and calling Margaret a “boozing, sex-starved psychopath” who he once discovered having sex with several parking-lot attendants.

“He was really nuts,” Margaret says. “I couldn’t believe he had so much hate for me.”

Margaret became a Jehovah’s Witness. She moved to Hawaii and started painting big-eyed children swimming in azure seas with tropical fish. In these Hawaii paintings you can see small, cautious smiles begin to form on the faces of the children. Walter’s life wasn’t so happy. He moved to a fisherman’s shack in La Jolla, California, and began to drink from morning until night. He told the few reporters still interested in him that Margaret was in league with the Jehovah’s Witnesses to defraud him. One reporter, from USA Today, believed every word, and they ran a story on Walter’s plight: “Thinking he was dead [Margaret] claimed to have done some of the Keane paintings. The claim, vehemently denied by a very much alive Keane, is in litigation.”

Margaret sued Walter. The judge challenged them both to paint a child with big eyes, right there in court, in front of everyone. Margaret painted hers in 53 minutes. Walter said he couldn’t because he had a sore shoulder.

“And there it is,” she tells me. She points to a framed portrait on the wall of a little girl with absolutely huge eyes, peering out nervously from behind a fence. “I painted it in Honolulu federal court. It has the exhibit number on the back.”

In fact the walls of Margaret’s home are filled with big-eye paintings – children, poodles, kittens. There’s barely an inch of empty wall space.

“That painting is symbolic of her triumph over the lies,” Margaret’s son-in-law tells me as he walks past us towards the kitchen.

Margaret won the court case, of course. She was awarded $4m, but she never saw a penny of it because Walter had drunk his fortune away. A court psychologist diagnosed him with a rare mental condition called delusional disorder. I ask Margaret if she knows anything about delusional disorder. She shakes her head and says she can’t even remember Walter being diagnosed with it.

“It’s when a person who is otherwise completely normal has a particular delusion they’re absolutely convinced of,” I say. “Quite often it’s a jealous husband convinced his wife is cheating on him. Sometimes the person is convinced that some impostor is taking credit for their genius.”

“I didn’t know that,” Margaret says.

“If you have the disorder it means you truly believe it,” I say.

Margaret thinks. “For a long time I felt very guilty about it,” she says.

“Why guilty?” I ask.

“If I hadn’t allowed him to take credit for the paintings, he wouldn’t have got as sick as he got.”

Walter died in 2000. He gave up drinking towards the end, but you get the sense that he missed those days, writing in his memoir that sobriety was his “new awakening, away from the drinking world of exciting sexy beautiful women, parties and art buyers”. By the 1970s, the big eyes had fallen from favour. Woody Allen mocked them in Sleeper, imagining a ridiculous future where they were revered.

But now, suddenly, there is a kind of renaissance. A Tim Burton biopic, Big Eyes, is about to be released, starring Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz. Margaret has a cameo: “I’m a little old lady sitting on a park bench.”

“Was the film distressing to watch?” I ask her.

“It was really traumatic,” she says. “I really think I was in shock for a couple of days. Christoph Waltz – he looks like Walter, sounds like him, acts like him. And to see Amy going through what I went through … It’s very accurate. Then it started to dawn on me how fantastic the movie is.”

Margaret smiles, looking thrilled, and I realise that sometimes a wrong is so great it needs something as dramatic as a major biopic in which you’re the hero to heal the wounds.

• Big Eyes will be released in the UK on 26 December.

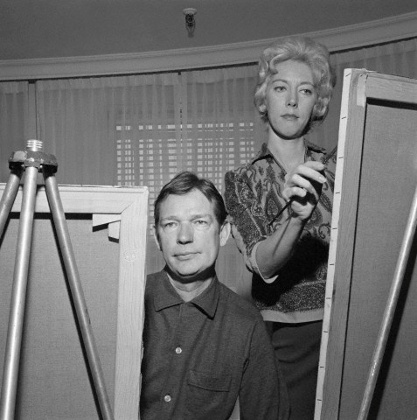

《大眼睛》導演提姆波頓(左起)、基恩、片中男女主角。(美聯社)

《大眼睛》導演提姆波頓(左起)、基恩、片中男女主角。(美聯社)

沒有留言:

張貼留言