Account

Critic’s Pick

Wifredo Lam: Artist-Poet of Tropical Dreams and Sorrows

The great Cuban modernist, whose politics and Afro-Asian roots shaped his paintings and inspired generations of artists, gets a revelatory survey at MoMA.

Wifredo Lam, “Sol (Sun),” 1925. Possibly a self-portrait, oil on burlap.Credit...Succession Wifredo Lam, Adagp, Paris/ARS, NY; via The Museum of Modern Art, New YorkWifredo Lam, “La Guerra Civil,” 1937, shows a scene of Fascist troops slaughtering Spanish citizens. The painting — a chaos of swipes and blotches in a dimensionless space — conveys the bad-dream emotion of a world in a state of emergency.Credit...Succession Wifredo Lam, Adagp, Paris/ARS, NY; Guarionex Rodriguez for The New York Times出生於古巴、後移居歐洲的超現實主義畫家威爾弗雷多·拉姆(Wilfredo Lam)於週六在巴黎家中去世,享年80歲。他已患病多年。

拉姆先生的作品涵蓋繪畫、雕塑和版畫,二戰後在美國獲得了廣泛關注。他的畫作曾在古根漢美術館和紐約現代藝術博物館展出。他的作品《叢林》(The Jungle)融合了歐洲、亞洲和非洲的藝術風格,曾懸掛在紐約現代藝術博物館位於西53街的舊入口處。 1964年,他榮獲古根漢國際獎展2,500美元獎金。

他最近一次在紐約舉辦的展覽是去年六月在皮耶馬蒂斯畫廊舉辦的,展出的是他的早期作品。拉姆先生是超現實主義運動的主要領導者之一。他曾為安德烈·布雷頓(André Breton)的一首詩作繪製插圖,之後加入了超現實主義運動。布雷頓於1922年參與創立了超現實主義運動。 “略帶神秘色彩”的主題

根據與林先生相識的美國藝術家羅瑪爾·比爾登(Romare Bearden)所說,林先生的創作主題「略帶神秘色彩」。 「這些主題似乎是他古巴經歷的產物。他的作品略帶超現實主義和立體主義的風格。而且,他的作品有一種單色調的特質;他的畫作色彩並不鮮豔。此外,他的人物、植物和樹木的形態也具有線條感。”

比爾登先生補充說:“在歐洲,林先生無疑被認為是20世紀的藝術大師之一,與萊熱、布拉克、馬蒂斯和畢加索齊名。”

在今年發表於國際季刊《黑人藝術》(Black Arts)的一篇文章中,林先生向赫伯特·根特里(Herbert Gentry)講述了他作畫的原因:「這是一種方式——我與人溝通的方式。這只是人們可以自由表達的眾多方式之一。」有些人會用音樂,有些人會用文學,而我則用繪畫。 」

他還告訴居住在歐洲的美國藝術家詹特里先生,他的繪畫靈感來自他的教母。曾參加西班牙內戰

他身材高挑,略顯消瘦,全名是威爾弗雷多·奧斯卡·德拉·康塞普西翁·拉姆·伊·卡斯蒂利亞,出生於薩瓜拉格蘭德。他的名字通常被寫成維弗雷多,沒有“l”。他在哈瓦那求學,10年代中期離開古巴前往西班牙。

1936年至1939年,他參加了西班牙內戰,為共和軍而戰。戰爭結束後,他移居巴黎。 1940年,他返回古巴,之後訪問美國,又回到歐洲。晚年,他的成就使他得以在義大利、瑞典和法國都擁有房產。

1980年,他應古巴政府邀請(他一直與古巴保持聯繫)參加了在哈瓦那舉行的五一勞動節示威遊行,這是他最後一次公開露面之一。

他的妻子露和三個兒子埃斯基爾·索倫、奧貝尼和伊恩·埃里克·蒂穆爾健在。

WILFREDO LAM, 80, A PAINTER, IS DEAD

By C. Gerald FraserSept. 13, 1982

Wilfredo Lam, a Cuban-born Surrealist painter who lived in Europe, has died at his home in Paris, friends said Saturday. He was 80 years old and had been ill for years.

Mr. Lam's work - paintings, sculpture and graphics - gained its greatest attention in the United States after World War II. His paintings have been exhibited at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. ''The Jungle,'' a blend of European, Asian and African influences, hung at the Modern's old entrance on West 53d Street. In 1964, he won a $2,500 prize at the Guggenheim International Award Exhibition.

His most recent New York exhibition, at the Pierre Matisse Gallery last June, was devoted to his early work. Mr. Lam was a principal leader of the Surrealist movement, which he joined after having illustrated a poem by Andre Breton, who, in 1922, helped to create the movement. 'Somewhat Mystical' Themes

Mr. Lam's themes were ''somewhat mystical,'' according to Romare Bearden, the American artist, who knew him. ''These themes seemed to have been evolved through his experience in Cuba. His work bordered a bit on Surrealism and Cubism. And there was a kind of monochromatic quality; his paintings were not bright in color. There was also a linear quality in his figures and his plant and tree forms.''

Mr. Bearden added that ''Lam is certainly considered in Europe as of one of the 20th-century masters, along with Leger, Braque, Matisse and Picasso.''

In an article this year in Black Arts, an international quarterly, Mr. Lam told Herbert Gentry why he painted: ''It's a way - my way of communicating between human beings. Just one of the ways one can try to explain with full liberty. Some will do it with music, others with literature, I with painting.''

He also told Mr. Gentry, an American expatriate artist living in Europe, that he was inspired to paint by his godmother. Fought in Spanish Civil War

A tall, gaunt, man whose full name was Wilfredo Oscar de la Concepcion Lam y Castilla, he was born in Sagua la Grande. His first name was often given as Wifredo, without the ''l.'' He studied in Havana and in the mid-20's left Cuba for Spain.

From 1936 to 1939, he fought with the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. By war's end he had moved to Paris. He returned to Cuba in 1940 and later, after visiting the United States, went back to Europe. By the end of his life, his success allowed him to establish homes in Italy and Sweden as well as in France.

In 1980, he was invited by the Cuban Government, with which he had maintained ties, to a May Day demonstration in Havana, where, he made one of his last public appearances.

Surviving are his wife, Lou, and three sons, Eskil Soren, Obeni and Ian Erik Timour.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York #WifredoLam was a Cuban artist of Afro-Chinese descent, renowned for using art as what he later called an "act of decolonization."

In the 1930s and 1940s, he created his own visual glossary of Afro-Caribbean deities and spirits, fusing them with modes of representation that drew on European Cubism and Surrealism. He referenced West African religions such as Santeria (or Lucumi) and Vodoun (or Vodou) that incorporated indigenous Taíno practices as they spread throughout the Antilles.

See his work—a testament to the enduring legacies of Afro-Latinx modern art—alongside 40 objects that celebrate the Caribbean's ancestral traditions in

#ArteDelMar.

Explore the exhibition online and in-person through bilingual resources

met.org/ArteDelMar

met.org/ArteDelMar----

#WifredoLam fue un artista cubano de ascendencia Afro-china reconocido por usar su arte como lo que él llamaba un "acto de descolonización".

En los 1930s y 1940s, Lam creó su propio vocabulario visual de deidades y espíritus Afro-caribeños, fusionándolos con modos de representación inspirados en el Cubismo y el Surrealismo europeos. En su arte, Wilfredo Lam hacía referencia a las religiones del África occidental, como Santería (o Lucumí) y Vodoun (o Vodou), que incorporaron las practicas taínas en su expansión por las islas antillanas.

Vea su obra -un testamento a los perdurables legados del arte moderno Afro-Latinx- junto con 40 objetos que celebran las tradiciones ancestrales del Caribe en

#ArteDelMar.

Explore la exposición virtualmente o en persona a través de recursos bilingües

met.org/ArteDelMar

met.org/ArteDelMar

Wifredo Lam (Cuban, 1902–1982). Rumblings of the Earth (Rumor de la tierra), 1950. On view in Gallery 359.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Cantor, 1958.

#LatinxHeritageMonth

Tate Explore in 360: Cuban dancer and choreographer Miguel Altunaga responds to The EY Exhibition: Wifredo Lam.

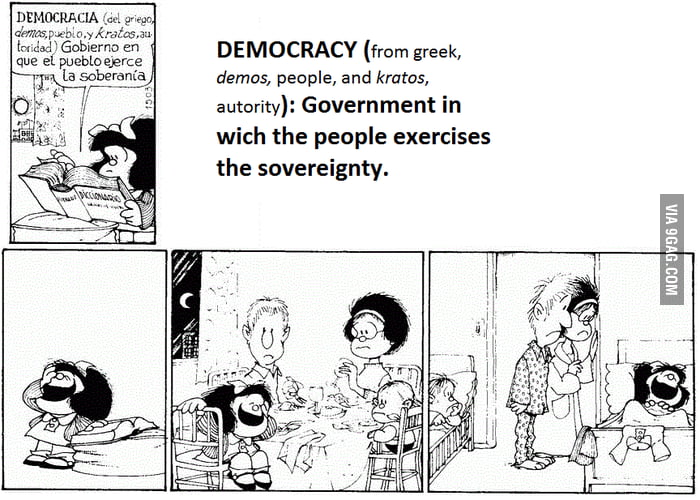

Statue of Mafalda in the "Paseo de la Historieta", Buenos Aires.

Statue of Mafalda in the "Paseo de la Historieta", Buenos Aires.

Wifredo Lam (Cuban, 1902–1982). Rumblings of the Earth (Rumor de la tierra), 1950. On view in Gallery 359.

Wifredo Lam (Cuban, 1902–1982). Rumblings of the Earth (Rumor de la tierra), 1950. On view in Gallery 359.