Featured Artwork of the Day: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864–1901) | Woman before a Mirror | 1897 http://met.org/13SvxKt

British Museum 新增了 2 張相片。

As you might have seen on today's Google doodle, it's Toulouse-Lautrec's 150th birthday! Here’s his poster for a Parisian cabarethttp://ow.ly/ExYlD

Fan of Toulouse-Lautrec? Browse British Museum Shop's wonderful range of art prints and books http://ow.ly/ExYLW

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Le Lit (vers 1892)

Huile sur carton, 53,5 x 70 cm.

Paris, musée d'Orsay. Legs Antonin Personnaz,1937

Huile sur carton, 53,5 x 70 cm.

Paris, musée d'Orsay. Legs Antonin Personnaz,1937

Absinthe makes the heart grow fonder. Join us for Toulouse-Lautrec after-hours 10/16 & 10/22. http://bit.ly/1ti5BTG

[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. "Reine de joie (Queen of Joy)." 1892]

Learn about Toulouse-Lautrec's nightlife through food, drink, and an after-hours tour. http://bit.ly/1rSyYt8

[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. "La Troupe de Mademoiselle Églantine (Mademoiselle Églantine’s Troupe)." 1896]

羅特列克

Toulouse-Lautrec

- 作者: Bernard Denvir/著

- 原文作者:Bernard Denvir

- 譯者:張心龍

- 編者:曾淑正

- 出版社:遠流

- 出版日期:1995/

本書揭開羅特列克的神祕面貌,從他的貴族階級背景、教育與藝術的修養、性格及身體缺陷等方面,探索其人其畫的內在靈魂。羅特列克的畫作大都取材自他的生活場域──劇院、酒吧、咖啡館和妓院;在淋漓盡致表現這些小人物的同時,他也充分揮灑了自己豐富而深刻的生命力。義大利導演費里尼曾說:「我一直覺得,羅特列克似乎是我的兄弟和朋友。這可能是因為他在盧米埃兄弟之前便已預示了電影的視覺技巧,可能是因為他常常站在被社會輕視、遺棄者的一方。每當我看到羅特列克的油畫、海報或版畫時,總是深為感動。我永遠忘不了他。」這也許為羅特列克作了最好的註解。

See this image

See this imageToulouse-Lautrec (World of Art) Paperback – July 1, 1991

by Bernard Denvir (Author)

This account of Toulouse-Lautrec strips away the mythology to look afresh at his achievements both as a graphic artist and a painter. It revitalizes and adds depth to the well-known images, while a wealth of contemporary material (correspondence, reviews, anecdotes and reminiscences) sheds new light on the challenges that faced the artist. Bernard Denvir examines all the major influences on his life and work: the eccentricities and instabilities of his aristocratic background; the indignities of his handicaps; his education and artistic training; the theatres, bars, cafes and brothels to which he increasingly gravitated; and the political and social unease of late nineteenth-century France. 170 illus., 31 in color.

----

這本書的譯者很粗心,連小仲馬 (Dumas fils) 都翻譯成"杜馬˙菲爾"(頁138)。

------

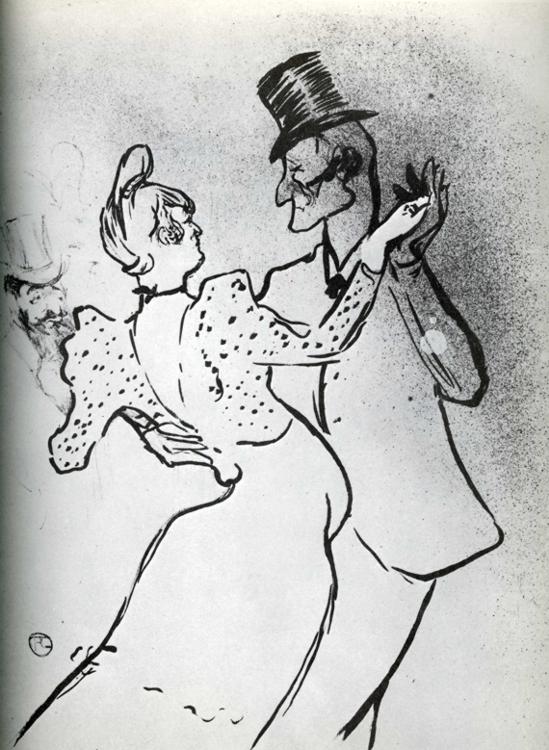

另外可能有他的專書。再次讀The Oxford Companion to Art 他的詞條,選兩幅:

Oscar Wilde 1895

---

French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec died #onthisday in 1901. Here’s a lithograph from his Elles suite http://ow.ly/AXAyA

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_de_Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa or simply Henri de Toulouse-Lautrecwas a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman and illustrator whose ...

- STATE OF THE ART| 29 July 2014

- How to cook like Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Reine de Joie by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – 1892 (Peter Harholdt/CORBIS)Grilled grasshoppers anyone? Or stewed porpoise perhaps? These are just some of the extravagant recipes in the great French artist’s cookbook. Alastair Sooke takes a look.

No artist captured the bohemian underworld of 19th-Century Paris with the wit and verve of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). His paintings and posters of cabarets, cafes, dancehalls and brothels define the way we still think of the hilltop demimonde of Montmartre, which in Lautrec’s day was a pleasure-seeker’s shadowland at the limits of respectability. Lautrec, a gregarious and free-spirited aristocrat who loved drinking, women and fancy dress, is now chiefly remembered as the chronicler of the seedy, uninhibited side of the belle époque.Rather less well known is that in addition to being a brilliant artist, Lautrec was also a fantastically inventive chef. Recently a friend gave me a second-hand copy of The Art of Cuisine, a compendium of his memorable recipes published decades after his death that provides many insights into his life and times.Food doesn’t feature prominently in Lautrec’s art. A still life with a pear appears in the foreground of a late painting set inside a private dining room in a cafe-restaurant, perhaps the Rat Mort, which Lautrec used to visit in the second half of the 1890s. But in the interior’s artificial light, the fruit looks sickly, ghoulish and thoroughly unappetising.

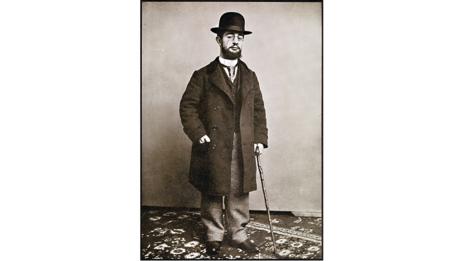

A genetic condition stunted Toulouse-Lautrec’s growth after he fractured both legs as a teenager (Classic Image / Alamy)

A genetic condition stunted Toulouse-Lautrec’s growth after he fractured both legs as a teenager (Classic Image / Alamy)

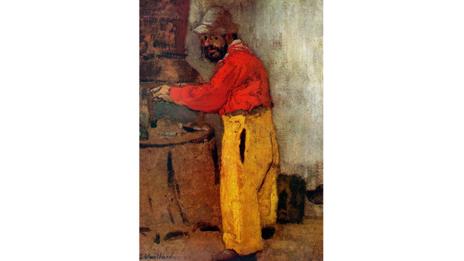

In general, the cafe tables in Lautrec’s pictures are bare, furnished at most with a few small plates or the odd glass of wine or green absinthe. Lautrec, himself, would die of complications arising from alcoholism when he was only 36 years old. A genetic condition stunted Lautrec’s growth after he fractured both legs as a teenager and he lived with a disability throughout his life.During his life, though, he enjoyed fine food as much as drink, and he threw frequent raucous, impromptu dinner parties for his wide circle of friends. According to one of them, the Symbolist poet Paul Leclercq, “He was a great gourmand… He loved to talk about cooking and knew of many rare recipes for making the most standard dishes… Cooking a leg of lamb for seven hours or preparing a lobster à l’Américaine held no secrets for him.” Indeed, his reputation as a confident and outlandish chef was so established that another friend, the artist Edouard Vuillard, painted a portrait of him standing in front of his oven.

A portrait of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec at Villeneuve sur Yonne (Vuillard Edouard, 1898)

A portrait of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec at Villeneuve sur Yonne (Vuillard Edouard, 1898)

Eclectic tastesHis surprising dishes included quails in ashes, thrushes in juniper, stewed fillets of porpoise (preferably “harpooned” from the bowsprit of a cutter in the English Channel), and “grasshoppers grilled in the fashion of Saint John the Baptist”. He also recommended other curious ingredients such as squirrel and heron.The recipes themselves, as recorded in The Art of Cuisine, are brief and idiosyncratic. Here, for instance, are his instructions for preparing stewed marmots: “Having killed some marmots sunning themselves belly up in the sun with their noses in the air one sunrise in September, skin them and carefully put aside the mass of fat which is excellent for rubbing into the bellies of pregnant women… Cut up the marmot and treat it like stewed hare which has a perfume that is unique and wild.”But perhaps his most amusing and renowned recipe was for “baked kangaroo”. Conceived in honour of an animal that he had seen boxing at the circus, then a popular Parisian entertainment, it involved fashioning an artificial pouch and attaching this to a great hunk of mutton.Lautrec is credited with introducing cocktail food to Paris, as well as for inventing a drink known as the “Earthquake”: three parts absinthe to three parts cognac, served with ice cubes in a wine goblet. However, although he is sometimes described as the inventor of chocolate mousse, this was not the case, since his “chocolate mayonnaise” was actually a variation of a recipe that had already appeared in French cookbooks. While we are on the subject of Lautrec’s desserts, though, my favourite is his recipe for “nuns’ fritters” – flavoured with rum.Not all of his dishes were mischievous or unusual. Many of his recipes reflect the hearty, no-frills culinary traditions of southern France, where he was born and raised as a gentleman in Albi, not far from Toulouse. “A heavily meat-based gastronomy was, and still is, a key part of that region’s cultural identity, and Lautrec would have been brought up in this farm-to-table mentality,” says Karen Serres, curator of paintings at theCourtauld Gallery in London. “His mother continued to send him products from the family estate when he was in Paris.”

In a Private Dining Room (At the Rat Mort) also known as Tete-a-tete supper by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1899 (The Samuel Courtauld Trust, London)

In a Private Dining Room (At the Rat Mort) also known as Tete-a-tete supper by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1899 (The Samuel Courtauld Trust, London)

Moreover, his interest in cooking should be understood in the context of the wider passions and pursuits of the era. “The 19th Century was a golden age of French gastronomy,” explains the food and art historian Janine Catalano. “Parisian artists frequently depicted the pastimes of the modern world, and many of them centred around food and drink – from meals in restaurants to picnics in newly designed parks to the night-time entertainments of bars and cabarets. And, of course, the artists engaged in these activities themselves. Monet was a notorious gourmand – he was particularly fond of morel mushrooms – and he would host generous picnics and dinner parties. His famous home in Giverny boasted not only water-lily ponds, but also acres of vegetable gardens and orchards.”In other words, Monet and Lautrec were representative of the times: according to Alexandra Leaf, writing in the preface to The Art of Cuisine, Paris boasted 27,000 cafes and more drinking establishments than any other city in the world by the end of the 19th Century. In addition, says Leaf, “The construction of Les Halles (1851-54), the great food market in Paris, ensured that the freshest, finest, and most flavourful comestibles, whether delicate white asparagus from Argenteuil or exquisite Belon oysters from Brittany, were readily available to all who desired them and had the means to procure them.” Records do not reveal whether Les Halles could supply Lautrec with his more outré ingredients.

A café scene by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1894-1895 (Francis G. Mayer/Corbis)

A café scene by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1894-1895 (Francis G. Mayer/Corbis)

Art of diningPerhaps the most important question of all, though, is how much Lautrec considered cooking an extension of his art. According to one anecdote, he saw parallels between the two. Vuillard recalled an occasion when Lautrec cut short one of his feasts after the cheese course by inviting his guests to follow him to a friend’s apartment, where an unknown masterpiece by Degas was hanging on the wall. Pointing at the painting, he said: “There is your dessert!”According to another story, Lautrec once prepared his famous lobster dish in front of an audience in a friend’s elegant drawing room, rather than in the kitchen. This sounds like a piece of performance art before its time. Today, for instance, the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija is known for installations that involve sharing meals and cooking.“I am wary of drawing direct parallels between Lautrec’s art and his cooking,” says Serres, “but the obvious link is his experimental attitude to both. Lautrec had a very inventive attitude to cooking, which he considered an extension of his bohemian and subversive attitude to authority. Likewise, in his art, he shunned the traditional oil paint on prepared canvas that artists would be expected to use, and adopted a variety of media and different types of supports. On a practical level, there is a similar attitude in the preparation and processes of painting and cooking, with the mixing of ingredients [and] pigments – and wearing a protective apron – the combination of various elements to make a whole, the trial-and-error aspect. But beyond going back to his roots and the experimental nature of cooking, what interested Lautrec was the conviviality it engendered. A festive meal brought together different people and was truly an event, almost a performance.”Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph

![Absinthe makes the heart grow fonder. Join us for Toulouse-Lautrec after-hours 10/16 & 10/22. http://bit.ly/1ti5BTG

[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. "Reine de joie (Queen of Joy)." 1892]](https://scontent-a-pao.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xfa1/v/t1.0-9/s600x600/1966917_10153525194937281_7233029077631468709_n.jpg?oh=a2aa37516697ccfad362f9bbcae6f7fb&oe=54BBAC49)

![Learn about Toulouse-Lautrec's nightlife through food, drink, and an after-hours tour. http://bit.ly/1rSyYt8

[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. "La Troupe de Mademoiselle Églantine (Mademoiselle Églantine’s Troupe)." 1896]](https://scontent-a-pao.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xpa1/t31.0-8/q83/s720x720/10697285_10153504990627281_4192764827345157770_o.jpg)

沒有留言:

張貼留言