Paul Klee and the Bauhaus Hardcover – April 30, 1973 英譯本 Text: English, German (translation)

研究室:藝術學院 學歷. 德國杜塞道夫國立藝術學院畢業

《保羅.克利》

出版社:藝術家

作者:吳瑪俐 譯

裝訂:平裝

出版日:1987

這本書有的時候將Klee 翻譯成正確的"克雷" (第26頁);Weimar 翻譯成麥瑪 (23)有誤。

"1924年他在葉那Jena 藝術公會作品展的演講" (p. 26)另外一說:Jena 大學演講,英譯北書名 Klee on Modern Art他幻想"作品能有無限的寬廣度,能統合元素性、物理性的、內容的、風格的領域。"

How to Be an Artist, According to Paul Klee

Artsy Editors

Dec 21, 2016 5:23 pm

One of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century,

Paul Klee

was also a prolific teacher, serving as a faculty member of the

Bauhaus

school between 1921 and 1931. Promoting a theoretical approach to artmaking, the painter taught a variety of courses across disciplines, from bookbinding to basic design, and left behind over 3,900 pages in lecture notes. These documents, partly compiled in Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925), reveal the artist’s innovative and unusual lesson plans, which often provided students with a step-by-step approach to artistic expression. We’ve pulled some of his key lessons about art and design. Let’s start with the basics.

Lesson #1: Take a Line for a Walk

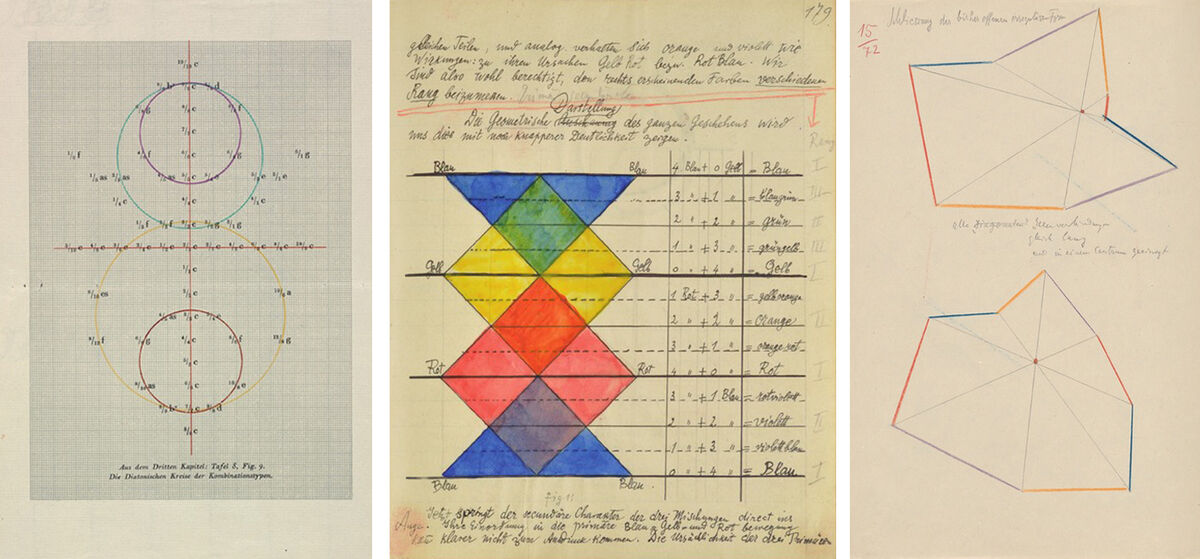

Pages from Paul Klee’s notes. Images via Zentrum Paul Klee.

“An active line on a walk, moving freely, without goal.” So begins Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook, which served as something of a textbook for many Bauhaus students. Five pages follow this famous description of the most basic of human marks, outlining the various types of lines, from those that circumscribe themselves to others that contain fixed points. Each example is accompanied by a diagram, which Klee likely drew on the blackboard during his lectures.

Many of Klee’s lessons center around this type of categorization, demonstrating the multiple ways in which a point can become a line, a line can become a plane, and so on. Beginning with the fundamentals, Klee modeled his teaching methods after the way children learn to read. “First letters, then symbols, then, finally, how to read and write,” he explained. Just as you can rearrange a series of letters to make different words, Klee would ask his students to repeat the same form in as many positions as possible. Such painstaking tasks would lay the groundwork for future works of art and design, and needed to be mastered before tone and color entered the picture.

Lesson #2: Observe a Fishtank

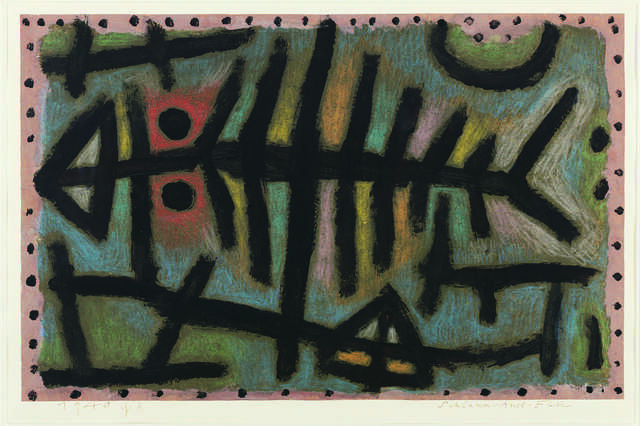

Schlamm-Assel-Fisch (Mud-Woodlouse-Fish), 1940

Fondation Beyeler

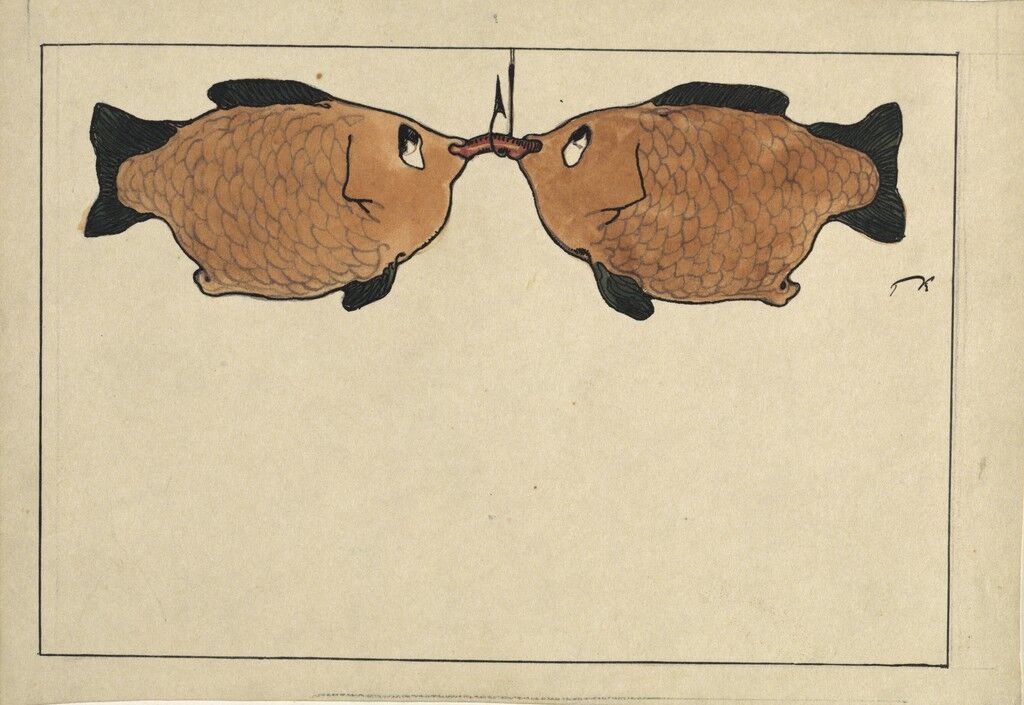

Sans Titre (Deux poissons, un hameçon, un ver), 1901

"Paul Klee: L'ironie à l'oeuvre" at Centre Pompidou, Paris

When Klee hosted classes in his home, he often required that students spend time observing the tropical fish in his large aquarium. The artist would turn the lights on and off, coaxing the fish to swim and hide, while encouraging students to carefully take note of their activity.

For those who know Klee as the “father of abstract art,” this lesson may seem surprising. However, Klee was deeply concerned with creating movement in his compositions. And he asserted that all artworks—even the most abstract—should be inspired by nature. “Follow the ways of natural creation, the becoming, the functioning of forms,” he taught his students. “Then perhaps starting from nature you will achieve formations of your own, and one day you may even become like nature yourself and start creating.”

Lesson #3: Draw the Circulatory System

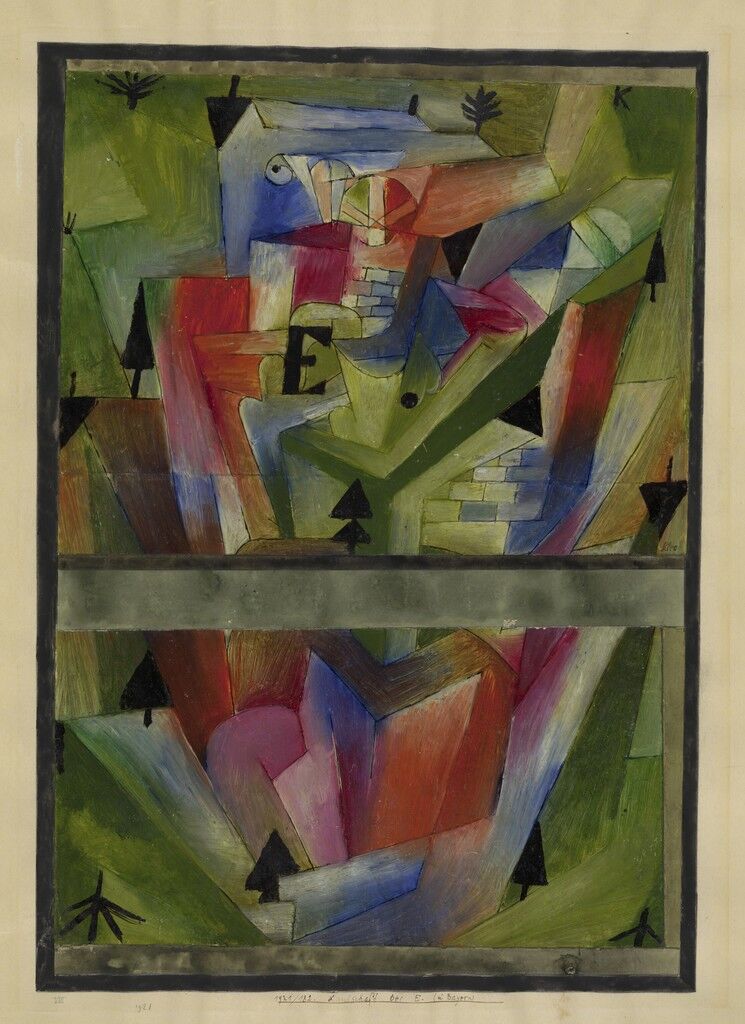

Paysage près de E. (en Bavière), 1921

"Paul Klee: L'ironie à l'oeuvre" at Centre Pompidou, Paris

Park near Lu, 1938

The EY Exhibition: Paul Klee - Making Visible, Tate Modern, London

Klee studied nature obsessively, and took a particular interest in the branching forms of plants, organ systems, and waterways. In his lectures, he described these patterns with scientific specificity, mapping mathematical equations and arrow-filled diagrams on the board. He explored how seeds sprout, how leaves develop ribs, and how lakes break off into streams, almost always ending with an awe-inspiring assertion about the magic contained in nature’s growth and development.

In one of these lessons, Klee explored the circulatory system, sketching on the chalkboard the movement of blood through the body. He claimed that this bodily process reflected the manner in which art is created. Afterwards, Klee asked his students to draw the circulatory system themselves. Their renderings, he insisted, should portray the transition of blood from stage to stage, shifting from red to blue, using line and density to represent shifts in weight, nutrients, and force. Go ahead, give it a try.

Lesson #4: Weigh the Colors

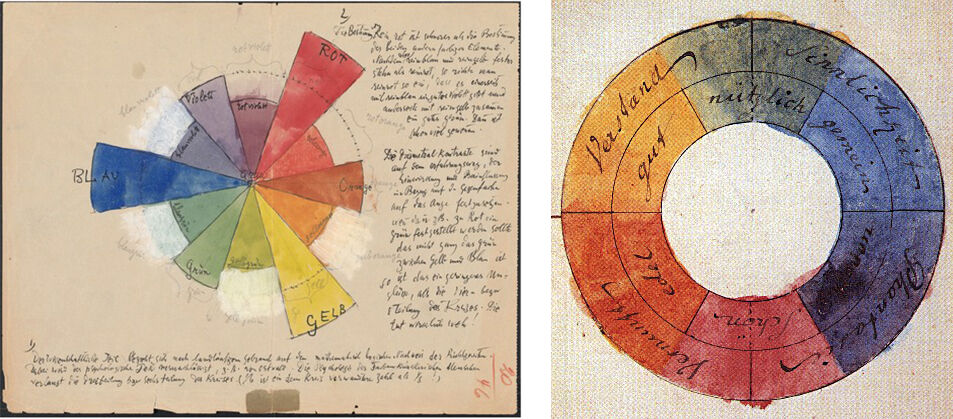

Left: Paul Klee’s color chart, from his notes. Image via Zentrum Paul Klee; Right: Goethe’s color wheel, published in Theory of Colours. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Only after students grasped the intricacies of lines and planes—and could find these forms in nature—did Klee introduce color. Like much of his teachings, Klee’s lessons about color combined scientific precision with a deep sense of mysticism. His theories primarily drew upon Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s color wheel, put forth a century earlier, in 1809, which proposed the idea that red opposed green, orange opposed blue, and yellow opposed violet.

Klee added a new dimension to this diagram, turning it into a sphere, with white at the top and black at the base. This framework, he taught, should encompass all aspects of color, including hue, saturation, and value. Klee required his students to create color diagrams of their own, including one assignment in which they visually weighed one color against another—the color red, as it turns out, is heavier than the color blue.

While grounded in science, Klee was also a romantic when it came to color. He often made connections between color and music, explaining that combinations of colors (much like musical notes) can be harmonious or dissonant depending on the pairing. He would sometimes even play the violin for his students. Klee’s most existential statement about color, however, came from beyond the classroom. “Color and I are one,” he declared in his diary in 1914. “I am a painter.”

Lesson #5: Study the Greats

When discussing the work of other artists, Klee used the following metaphor. If a new product like a toothpaste or a laundry detergent was popular with customers, its competitors should research the item’s chemical elements so that they could replicate the success. Or if a food induced illness, scientists should strive to determine which specific ingredients were poisonous and which were benign.

As such, artists should break down the artworks of their peers and predecessors into the most elementary components—line, form, and color—to determine what makes an image successful or problematic. “We do not analyze works of art because we want to imitate them or because we distrust them,” he once said. Instead, we do so “as to begin to walk ourselves.”

In his later years at the Bauhaus, Klee provided students with feedback on their works in his home. Students would bring in their fresh paintings and place them on empty easels, as Klee’s unfinished works hung in the background. Klee would sit, gliding back and forth in his rocking chair, and inspect the images in silence. Only then would he provide an analysis of the works, albeit in his famously lofty fashion, speaking to a larger problem in the field of painting or identifying a subconscious idea that manifested itself in the work. Afterward, the class would sit around a large, glazed clay pot, smoke cigarettes, and discuss artmaking. Of all the Bauhaus masters, Klee was the only one who did not give grades.

—Sarah Gottesman

Pedagogical Sketchbook is a book by Paul Klee. It is based on his extensive lectures on visual form at Bauhaus Staatliche Art School where he was a teacher in between 1921-1931. Originally handwritten – as a pile of working notes he used in his lectures – it was eventually edited by Walter Gropius, designed by László Moholy-Nagy and published in 1925 as a Bauhaus student manual (Bauhausbucher No.2, as the second in the series of the fourteen Bauhaus books) under the original title: Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch. It was translated into English by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (in 1953), who also wrote an introduction for it.

Along with other Bauhaus books such as Theory of Color (by Johannes Itten) and Point and Line to Plane (by Wassily Kandinsky), Pedagogical Sketchbook is a legacy of teaching methods on art theory and practice at Bauhaus Staatliche Art School.

The book is still in print.

Background[edit]

During his teaching career at Bauhaus, Klee reflected on his own working methods and techniques. “When I came to be teacher”, he wrote, “I had to account explicitly for what I had been used to doing unconsciously.” [1] He left over 3000 handwritten pages developed as a theoretical basis for his lectures, some of which are still unpublished. [2]

From the same period comes another one of his books: The thinking Eye, dealing with the same issues as Pedagogical Sketchbook, but much more extensive in scope. However, this book was published and translated later, after his death (1956; trans. 1961).

Teaching concept[edit]

Pedagogical Sketchbook is an intuitive art investigation of dynamic principles in visual arts. Klee takes his students on an ‘adventure in seeing’[3] guiding them step-by-step through a challenging conceptual framework. Objects are rendered in a complex relation to physical and intellectual space concepts. It is an exercise in modern art thinking.

In her introduction, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy divides the book into 4 different parts corresponding to the 4 conceptual frameworks. Each framework is illustrated by intricate drawings (mixture of what looks like creative arithmetic or geometry sketches, scribbles and mental notes).

Starting chapter concerns ‘Line and Structure’. A dot goes for a walk… freely and without a goal.[4] Dot is a “point of progression” and by shifting its position forward becomes a line. Line variations lead to even more complex structures. It can move freely in a calligraphic stroke, or circumscribe, act as a planar definition, as a mathematical structural element (as in Golden Section) or as a path in motion (when it coordinates kinetic movements such as in muscle contraction). Artist's world is dynamic – in the state of becoming – rather than static.

In ‘Dimension and Balance’, the line is related to psychological and social concepts of space. Klee explains subjectivity of our perception by comparing examples of optical illusion with horizon and perspective. We use them as orientation points within the space. As an illustration, Klee uses a stylized drawing representing a tightrope walker with a bamboo stick as a ‘horizon’ point, keeping his balance. These examples evoke our reality as constructed and arbitrary. “Dimension is in itself nothing but an arbitrary expansion of form into height, width, depth and time”.[5] By challenging conventional perception of his students, Klee shows them a way ‘beyond’ physical realm, into the world of metaphysical and spiritual. It is an invitation to approach art intuitively, since outer perception can be deceptive (socially constructed).

The third part is about “Gravitational Curve”. A very first drawing of a strong black arrow pointing downwards postulates man as a tragic figure always brought down by a plummet (a black arrow) of a gravitational force. However, Klee also points that water and atmosphere are transitional regions, where spirit gets lighter and breaks free. This is a spiritual space open to dynamic positions, new symbols and imaginative co-relations of visual elements (mechanical law of nature versus imaginative vision rendering of an object in art).

Continuing further into the final part of the manual ‘Kinetic and Chromatic Energy’, Klee gives examples of ‘creative kinetics’ defying gravitational force such as centripetal force in pendulum and spinning top, or a ‘feathered arrow’.[6] He continues with a ‘symbolic’ arrow illustrating similar efforts of a man to move ‘a bit further than customary – further than possible’.[7]

Last drawings in the book are related to chromatic and thermo-dynamic field where a color is put in relation to motion: “Motion that may be called infinitive…exists only in the activation of color moving between the fervid contrasts of utter black and utter white”.[8]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1968), Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber & Faber.

- Carola Giedion-Welcker, translated by Alexander Gode (1952), Paul Klee, New York: Viking Press

- Will Grohmann (1985), Paul Klee, Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Susanna Partsch (2000), Paul Klee 1879-1940, Taschen

- Magdalena Droste (1990), Bauhaus 1919-1933, Taschen

沒有留言:

張貼留言