Russian icons

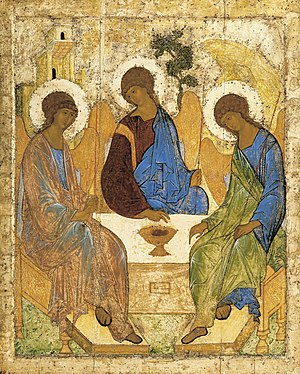

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity in AD 988. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by Byzantine art, led from the capital in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world.

The personal, innovative and creative traditions of Western European religious art were largely lacking in Russia before the 17th century, when Russian icon painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from both Protestant and Catholic Europe. In the mid-17th-century changes in liturgy and practice instituted by Patriarch Nikon resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists, the persecuted "Old Ritualists" or "Old Believers", continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice. From that time icons began to be painted not only in the traditional stylized and non-realistic mode, but also in a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism, and in a Western European manner very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. These types of icons, while found in Russian Orthodox churches, are also sometimes found in various sui juris rites of the Catholic Church.

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be much larger. Some Russian icons were made of copper.[1] Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner.

There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostas, иконостас), or icon-screen, a wall of icons with double doors in the centre.

Russians sometimes speak of an icon as having been "written", because in the Russian language (like Greek, but unlike English) the same word (pisat', писать in Russian) means both to paint and to write. Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint, and therefore careful attention is paid to ensure that the Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed.

Icons considered miraculous were said to "appear." The "appearance" (Russian: yavlenie, явление) of an icon is its supposedly miraculous discovery. "A true icon is one that has 'appeared', a gift from above, one opening the way to the Prototype and able to perform miracles".[2]

Contents

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_icons

Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography

Irina Konstantinovna I︠A︡zykova

Paraclete Press, 2010 - 194 ページ

0 レビュー

A true story—told for the first time This dramatic history recounts the story of an aspect of Russian culture that fought to survive throughout the 20th century: the icon. Russian iconography kept faith alive in Soviet Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution. As monasteries and churches were ruined, icons destroyed, thousands of believers killed or sent to Soviet prisons and labor camps, a few courageous iconographers continued to paint holy images secretly, despite the ever-present threat of arrest. Others were forced to leave Russia altogether, and while living abroad, struggled to preserve their Orthodox traditions. Today we are witness to a renaissance of the Russian icon, made possible by the sacrifices of this previous generation of heroes.

| 書籍名 | Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography |

| 著者 | Irina Konstantinovna I︠A︡zykova |

| 翻訳 | Paul Grenier |

| 寄与者 | Wendy Salmond |

| 版 | イラスト付き |

| 出版社 | Paraclete Press, 2010 |

| ISBN | 1557255644, 9781557255648 |

| ページ数 | 194 ページ |

沒有留言:

張貼留言