貝聿銘先生去世消息的隨想 (1)

今天在You Tube看貝聿銘先生的紀錄片:First Person Single

可知貝先生留美想學建築,先到著名的賓州大學去,兩周之後就因志向不同,知難而退,當時賓大也很重視建築繪圖,高手很多 ( 如果您看過梁思成先生等的作品,多少可知到該校風格。)

他轉學到MIT的建築學院的"建築工程"主修,1935年受到該校院長William Emerson (Dean of MIT School of Architecture , from 1932 to 1939)的鼓勵他轉到視野更寬廣的"建築"主修。

貝聿銘當時想打退堂鼓,理由是他的圖畫得不好.....院長說,"胡說,我知道每個中國人都擅長畫圖,你當然沒問題......"

貝聿銘先生說,他一直很感激William Emerson院長的鼓勵與指引,讓他走入建築師專業。

貝聿銘先生到哈佛大學去讀建築研究學院,當時兩位來自Bauhaus的老師,對他都有很大的啟發,首先是系主任/所長Walter Gropius,其明亮、新材料、社會建築等,都讓他受益;然而,他不太相信有放諸各國都通用的建築風格/方式。

另外一位Bauhaus老師是Marcel Breuer (1902~1981),與貝先生的關係、緣分更深遠。

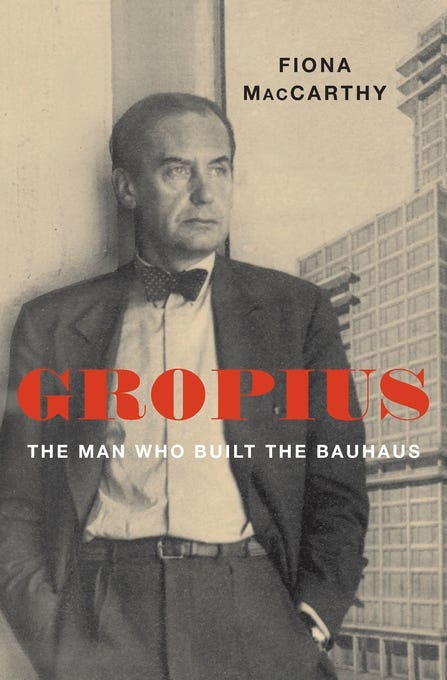

---- 傳言Walter Gropius先生不會畫圖 (其實,他的事務所或Bauhaus都有畫圖長才。)

As is well known — a much repeated truth tha大t has almost become a cliché — technical draughtsmanship was never to be Gropius’s strong point.眾所周知 - 一個人們耳傳之事實,它幾乎成為陳詞濫調 - 技術性繪圖能力,從未是格羅皮烏斯的強項。

Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus By Fiona MacCarthy

The impact of Walter Gropius can be measured in both his buildings and his influence on others. Between 1910 and 1930, Gropius was at the center of European modernism and avant-garde society glamor, only to be exiled to the antimodernist United Kingdom during the Nazi years. Later, under the democratizing influence of American universities, Gropius became an advocate of public art and cemented a starring role in twentieth-century architecture and design. In Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus, Fiona MacCarthy challenges the image of Gropius as a doctrinaire architectural rationalist, bringing out the visionary philosophy and courage that carried him through a politically hostile age. Here is a brief excerpt looking at his early life in Germany.

The ageing Walter Gropius looked back at his childhood, remembering an episode that struck him as significant: ‘when I was a small boy somebody asked me what my favourite colour was. For years my family poked fun at me for saying, after some hesitation, “Bunt ist meine Lieblingsfarbe,” meaning “Multicoloured is my favourite colour.”’ The colours of the rainbow were what he really loved. Gropius’s early yearnings for variety were serious and lasting: his appreciation of completely varied building styles, from classical Greek to twentieth-century Japanese; a love of music that included both Schoenberg and the Beatles; the improbable and sometimes inflammatory mixes of creative people he gathered in around him. As he put it in a speech made in Chicago on his seventieth birthday, ‘The strong desire to include every vital component of life instead of excluding them for the sake of too narrow and dogmatic an approach has characterised my whole life.’

Gropius was born on 18 May 1883 in Berlin, the rapidly expanding imperial capital where variousness had become a way of life. He was christened Adolf Georg Walter Gropius in the neo-Gothic Friedrichswerdersche Kirche, of which Karl Friedrich Schinkel was the architect. Growing up he was exposed to a whole commotion of architectural styles, Gothic and Romanesque, Baroque and neo-classical. The challenge of the city, as he came to comprehend it, was intriguing and dementing. What was the ideal city? And what were an architect’s responsibilities in the shaping of the city? After victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the unification of Germany in 1871, Berlin was emerging as a powerful and thriving European capital, a city on a par with London, Paris or Vienna. Its population grew from 826,000 in 1871 to 1.9 million in 1900. Alongside the excitements of expansion there were the inevitable social problems. Berlin, as Gropius watched it through its stages of transition from imperial to modern, was the place of his first loyalty, the city which first taught him that an architect had social obligations. Even when far away from Germany through his years of exile, Berlin was still the city that Gropius came back to in his architectural imagination.

Architecture was in his background. His father’s Prussian family was embedded in the solidly respectable high bourgeoisie. Gropius’s great-great-grandfather had been a parson in Helmstedt, a town in Lower Saxony. His descendants were predominantly clergymen, teachers, minor landowners and soldiers. But Gropius’s family had an entrepreneurial tendency as well. In the early nineteenth century his great-grandfather Johann Carl Christian Gropius became a partner in a Berlin silk-weaving works. Already there were family connections with the intricate skills of making and an intimate knowledge of materials, early precedents for the workshop practice on which Gropius’s Bauhaus philosophy was based.

Johann’s brother Wilhelm Ernst was the proprietor of a company making theatrical masks and, more ambitiously, acquired a theatre where he put on performances with landscape scenery and moving statuary magically animated and lit. Such entertainments were a popular feature of the city. The writer Walter Benjamin, who grew up in Belin, described the strange enchantments of these so-called dioramas. A little bell would ring before each moving image was revolved to face the expectant audience: ‘And every time it rang, the mountains with their humble foothills, the cities with their mirror-bright windows, the railroad stations with their clouds of dirty yellow smoke, the vineyards, down to the smallest leaf, were suffused with the ache of departure.’

Wilhelm Ernst’s two enterprising sons, inspired by Bouton and Daguerre’s famous Paris diorama, developed these techniques to create their own spectacular Gropius Diorama in Berlin. This consisted of three huge scenic paintings, each more than sixty foot wide and forty high, revolving in sequence accompanied by four-part choral music. The Gropius Diorama continued until 1850, and again one finds the family fascination with theatre paralleled in Walter Gropius’s later interest in performance, for instance his collaboration with Erwin Piscator on the concept of ‘Total Theatre’ as well as Oskar Schlemmer’s theatrical experiments of the Bauhaus years.

A key figure in developing the Gropius Diorama was the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. He was a protégé of both Johann Carl Christian and Wilhelm Ernst Gropius, who employed and encouraged him at an early stage of his career. Indeed for a time the young Schinkel was a lodger in a Gropius family house on Breitestrasse, near the silk works, sharing cramped accommodation on an upper floor where the aspiring architect ingeniously used painted folding screens as room dividers. It was Schinkel who provided the sketches, made in Paris in 1826, for the Gropius Diorama. Years later, after Schinkel himself had become renowned as the architect of many of Berlin’s great civic buildings — the Neue Wache, the Schauspielhaus theatre, the Altes Museum, Gropius’s christening place the Friedrichswerder church, the Bauakademie architectural school — he was to have a potent direct influence on the Gropius architectural dynasty.

Schinkel was certainly the role model for Walter Gropius’s successful great-uncle, Martin Gropius. He studied at the Bauakademie and formed one of the largest architectural firms in Berlin, Fa. Gropius & Schmieden. Martin Gropius absorbed the classical influence of Schinkel to design such well-proportioned and grandly urban buildings as the Gewandhaus in Leipzig and the Renaissance-style Kunstgewerbe-museum in Berlin, originally built as a royal art museum and now known as Martin Gropius Bau.

More poignantly, Gropius’s own father Walther Gropius, also inspired by Schinkel, started out with ambitions to become an architect. But according to Gropius, his father was too lacking in confidence, too timid and withdrawn for a profession that needed a certain flamboyance in approach. After only a short period of designing actual buildings he retreated into public service. He was working as a civic building official by the time his son Walter was born. However, his own thwarted ambitions never stopped him from supporting his son’s architectural beginnings. According to an old friend, the elder Walther Gropius was ‘the only really kind man’ he had ever known.

Walther Gropius assumed that his son would follow family tradition by becoming an architect in the formal urban Schinkel mode. In a sense he would not have been disappointed, for Gropius himself remained a staunch admirer both of Schinkel and of Schinkel’s own mentor David Gilly. In spite of the fact that Schinkel himself was stylistically promiscuous, veering from neo-classical to romantically medieval, his buildings had an overriding structural consistency, a mastery of space that Gropius admired. Even Adolf Loos, early-twentieth-century uncompromising modernist and anti-ornamentalist, recommended Schinkel to the newer generation as the exemplar of architectural purity. And for Gropius’s contemporary Mies van der Rohe, Schinkel ‘had wonderful constructions, excellent proportions, and good detailing’. Gropius’s father might have found his son’s later architectural work in some ways disconcerting but their shared admiration for Schinkel’s architectural mastery was unwavering.

Though it seems that Gropius’s father was sweetly ineffectual, Gropius’s mother was quite another matter. Manon Scharnweber Gropius, the descendant of French Huguenot émigrés who settled in Prussia in the seventeenth century, was a formidable woman, possessive and ambitious for her family. Young Gropius had three siblings: Elise, who was born in 1879 and who died in her early teens; a second sister, Manon, two years older than Walter, to whom he was devoted; and a younger brother, Georg, known in the family as Orda. Family life was sedate, contained and cultured. Walter Gropius ‘had Kultur in his bones’, as the historian Peter Gay described it. There were theatres and lectures, there was a lot of music, with family outings to operas, concerts and ballet in Berlin. Walter’s sister Manon was encouraged by their mother to accompany her brothers in trios and chamber music. Orda was a precociously talented violinist. Walter played the cello, but nothing like so well.

Walter and his mother were always particularly close, locked together in a fondness which would later prove a challenge to his wives. Alma’s response was confrontational, Ise’s more deviously conciliatory. The family lived at 23 Genthinerstrasse in the Schöneberg district on the west side of the city. This was a pleasant, highly respectable residential area close to the Tiergarten, the large public park. The Gropius apartment building stood in a leafy area of substantial houses, with the tall spire of the Apostelkirche, built in the 1870s in bright red-orange brick, dominating the end of the street.

Walter Benjamin, born ten years after Walter Gropius, was brought up in a Jewish but otherwise similarly comfortable, settled bourgeois household in the same part of the city. Benjamin’s memoir of his Berlin childhood gives an almost dreamlike impression of the area, with its formal mid-to late-nineteenth- century Gründerzeit architecture of prosperous, substantial houses with their inner courtyards and their loggias. ‘Everything in the courtyard’, wrote Benjamin, ‘became a sign or hint to me.’ Nearby there were hackney carriage stands on which the fascinated child watched the coachmen hang their capes while watering their horses. He remembered how the rhythm of the metropolitan railway and the distant sounds of carpet beating rocked him to sleep.

Walter Benjamin’s memoir was written in the early 1930s, before he, like Gropius, was forced to leave Berlin, and it exudes a sense of pending exile. Benjamin is thought to have eventually committed suicide on the French–Spanish border in 1940. There is a strange magic in his account of childhood. The statues in the Tiergarten, ‘the caryatids and atlantes, the putti and pomonas’, mystify the boy who, ‘thirty years ago, slipped past them with his schoolboy’s satchel’. He is struck by the curious sights and sounds from the zoo nearby, with its gnus and zebras, elephants and monkeys, accompanied by the distant music of the Tiergarten bandstand. In shopping expeditions to the city with his mother, he glimpses another side to Berlin life, the underworld of poverty, seeing with fascinated horror the beggars and the whores with their thickly painted lips. As Benjamin comments in his book, ‘I have made an effort to get hold of the images in which the experience of the big city is precipitated in a child of the middle class.’ Walter Gropius’s own upbringing, exposed to similar enchantments and terrors of the city, was very much like this.

At the age of six Gropius was sent to a private elementary school in Berlin, and then three years later he started a conventional classics-based education at the Humanistische Gymnasium, part of Berlin’s publicly sponsored educational system. He attended three of these gymnasia from 1893, finally leaving the Stegliz Gymnasium when he was nearly twenty. He had done so well in his final exams, which included submitting an impressive translation of Sappho’s ‘Ode’, that his proud father took him out to a lavish celebration dinner at Kempinski’s restaurant, where he toasted Walter’s successes with champagne.

Gropius was at this stage rather withdrawn, shy and solitary. His visual interests were still quite undeveloped. So far there were few signs of Gropius the influential architect. But he later claimed that his obsession with building structures had been fired while still at school by Julius Caesar’s account of the construction of the bridge across the Rhine, which Gropius discovered in The Conquest of Gaul. He had drawn it up according to Caesar’s description and constructed a scale model.

Not long after, in early 1903, he enrolled in the Munich Technische Hochschule to take an intensive course in architectural studies: history, design, building construction. This was his first time away from home. Gropius’s apartment in Munich was just a stone’s throw from the Alte Pinakothek picture gallery and the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, close to the university, the second-hand bookshops and the ancient courtyards tucked in behind the street facades. The young Gropius had spent his free hours in the museums, studying the Munich collections of German, Dutch and Italian Old Masters and discovering the work of the French Impressionists.

But he was not to stay in Munich long. First of all he was officially summoned to start his compulsory year’s military service in the late summer of 1903. Then there was intense family anxiety about the serious illness of his younger brother Orda, who was suffering from what seems to have been the kidney disorder later to be known as Bright’s disease. Gropius decided to postpone his military training and returned home to Berlin in July. After months of painful illness, in January 1904, Orda died. This shock affected Walter profoundly. He stayed on in Berlin comforting the family and entered the architectural firm of Solf and Wichards, two Berlin architects who were family friends, as a by then relatively mature apprentice. Although he began as a draughtsman in the office, his true talent for practical construction was quickly recognised and he was soon being sent out on site work, controlling the concept and architectural detailing of buildings. As is well known — a much repeated truth that has almost become a cliché — technical draughtsmanship was never to be Gropius’s strong point.

Finally, in the summer of 1904 Gropius reapplied for his military service with the 15th Hussars stationed at Wandsbeck near Hamburg. He wrote home to his mother, optimistically telling her he was living comfortably in a big old rural Gasthof. He added with a characteristic touch of vanity, ‘My uniforms fit me well and I shall look very elegant in them.’ A photograph of the slim and upright Walter Gropius as a cadet in the Hussars’ splendid uniform, staring boldly ahead, definitely bears this out. Probably he looked even better on his horse.

沒有留言:

張貼留言