Since antiquity, the art of Classical Greece has exerted a special hold over powerful and wealthy collectors. The Roman emperor Hadrian, who was so enamoured with Greek culture that he earned the nickname ‘Graeculus’, or ‘Greekling’, adorned his sprawling Villa at Tivoli east of Rome with reproductions of famous Greek artworks. During the Renaissance, cardinals and popes vied to own the masterpieces of Greek art emerging from Italy’s soil. And in the 18th Century, during the heyday of the Grand Tour, gentlemen from across Europe descended upon Italy to buy up as much ancient art as they could.

But in the 20th Century, the afterlife of ancient Greek art took a darker turn. To understand what I mean, just watch the famous opening sequence of Leni Riefenstahl’s two-part film Olympia (1938), which documented the Berlin Olympics, otherwise known as the “Nazi Olympics”, held two years earlier.To a soundtrack of dramatic music, the camera moves slowly across the ruins on the Athenian Acropolis, before lingering on several celebrated ancient sculptures, offered up as ideals of beauty and artistic prowess. Eventually, against a mist-swathed backdrop, we see one of the most famous Greek sculptures of all: a statue of a stooping, naked athlete preparing to hurl a discus. To connoisseurs of ancient art, this is known as the Discobolus (or “discus-thrower”).

Its surface glistening with oil, as though ready for competition, the sculpture suddenly fades away. In its place appears a living athlete adopting the same pose. Slowly he starts to swivel back and forth, before hurling his discus with all his might. The chilling message is presented with stark, poetic efficiency: the glories of Classical Greece are reborn in Nazi Germany.

‘Vigour and beauty’

As I discovered while filming a new BBC television series about ancient Greek art, Riefenstahl was being canny by focusing on the Discobolus – since Adolf Hitler was arguably more infatuated with this artwork than any other. In fact, Hitler was so besotted with it that, in 1938, he bought it.

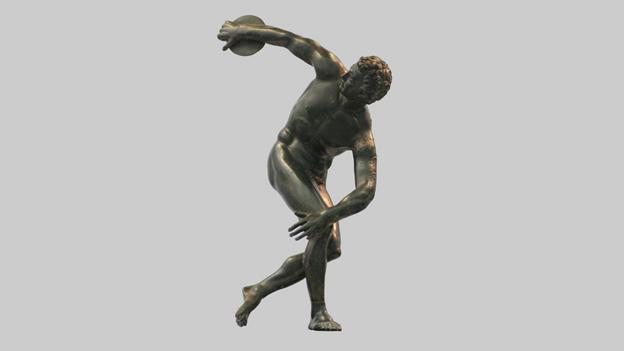

The original sculpture, now lost, was created in bronze by Myron in Greece in the 5th Century BC (Credit: Rotatebot/Wikipedia)

The statue in Riefenstahl’s film is actually a Roman marble copy of the bronze original by the Greek sculptor Myron, one of the masters of Classical art in the 5th Century BC. Myron was feted for his ability to produce artworks of astonishing realism, including a stunning bronze cow on the Acropolis. In the Discobolus, he innovated by capturing an athlete mid-action. To do this, he employed a powerful, spiralling composition, implying a payload of pent-up energy.

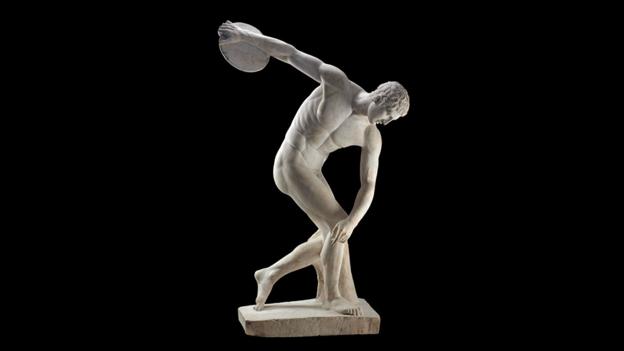

Today Myron’s lost sculpture is known via several marble copies, including the so-called ‘Townley Discobolus’ in the British Museum. Discovered in 1791 in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, but inaccurately restored so that its head faces in the wrong direction, this sculpture is a centrepiece of Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, a major new exhibition at the British Museum.

The version of the sculpture that beguiled Hitler, though, was another replica known as the ‘Lancellotti Discobolus’, named after the Italian family that once owned it. Discovered in a property belonging to the family on the Esquiline Hill in 1781, it is now in the National Museum in Rome.

Hitler was not the first political leader in modern history to view Greek art as a potent status symbol: Napoleon, for instance, was obsessed with the Venus de’ Medici. But the fact that Hitler, who had strong views about visual art, fixated upon the Discobolus is significant.

The Nazis drew aesthetic inspiration from ancient Greece and Rome and the Discobolus featured prominently in the opening of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (Credit: Tobis-Filmverleith)

For one thing, he wanted to be associated with the era in which it was created: the 5th Century BC had long been considered the golden age of Classical Greek history, when Athens under Pericles witnessed the construction of the Parthenon. In addition, he wished to champion the values that he believed the sculpture embodied – ideals of harmony, athletic vigour and beauty – in opposition to Modernist art, which he castigated as “degenerate”.

Antique’s roadshow

Hitler’s opportunity to acquire the statue arose in the 1930s, when the Lancellotti family fell upon hard times and offered it for sale. At first the sculpture was earmarked for the Metropolitan Museum in New York, but the original asking price of eight million lire was deemed too high. By 1937, Hitler had made known his interest in the statue, and the following year, despite initial misgivings on the part of the Italian authorities about exporting it, the Discobolus was sold to him for the still huge sum of five million lire. Funded by the German government, this was delivered in cash to representatives of the Lancellotti family in their palazzo.

By the end of June 1938, the Discobolus had arrived in Germany where it was displayed not in Berlin but in the Glyptothek museum in Munich. On 9 July it was officially presented as a gift to the German people. Hitler addressed the crowds: “May none of you fail to visit the Glyptothek, for there you will see how splendid man used to be in the beauty of his body… and you will realise that we can speak of progress only when we have not only attained such beauty but even, if possible, when we have surpassed it.”

The marble copy of the Discobolus in the British Museum was incorrectly restored so that the head faces the wrong direction (Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum)

“Without the Classical tradition, the Nazi visual ideology would have been rather different,” says Professor Rolf Michael Schneider of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “Like all hunters, they hunted for a priceless object – and as the statue could not say no, they used the Discobolus for their perverse ideologies. The perfect Aryan body, the white colour [of the marble], the beautiful, ideal white male: to put it very bluntly, it became a kind of image of the Herrenrasse or ‘master race’ – that’s what the Nazis called themselves and the Germans.”

In other words, the Discobolus became a pin-up boy for Nazi propaganda: as Ian Jenkins, senior curator of the ancient Greek collections at the British Museum, puts it, it was co-opted as a “trophy of the mythical Aryan race”. And even though its stay in Germany was no more than a decade (in 1948 the statue returned to Italy, and it was placed in Rome’s National Museum five years later), it would be a long time before the taint of its association with Hitler disappeared.

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph

沒有留言:

張貼留言