Unexpected Eisenstein

February 17, 2016 | by Rob Sharp

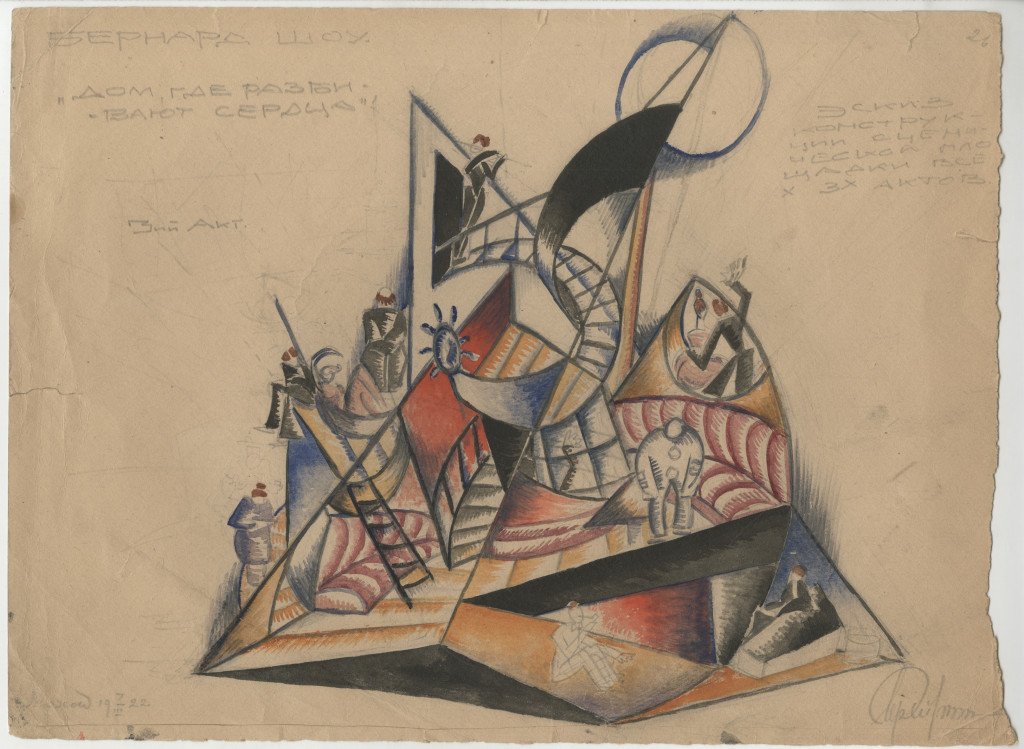

Sergei Eisenstein, Set design for Act III of Heartbreak House (unrealised), 1922, paper, pencil, ink and watercolour on paper ©Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

In November 1929, the thirty-one-year-old Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was the world’s most notorious film director. Four years earlier, Battleship Potemkin, his euphorically reviewed, highly influential tour de force about mutiny on the eponymous naval vessel, had brought him both acclaim and infamy. Infected with wanderlust, Eisenstein won permission from Stalin to leave Russia on a short research trip. He took off in August 1929, with twenty-five dollars in his pocket. He returned home, reluctantly, just under three years later.

During the ensuing whirlwind—to Berlin, Paris, London, then on to Hollywood—Eisenstein met with the world’s leading intellectuals, actors, and avant-garde artists: James Joyce, Jean Cocteau and Robert Desnos in France, George Bancroft in Germany, Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich and Gary Cooper in the United States. His grand tour often gets overshadowed by his disastrous film collaboration in Mexico with the novelist Upton Sinclair—framed in Peter Greenaway’s 2015 movie Eisenstein in Guanajuato—but British culture was a significant and often neglected long-term source of interest.

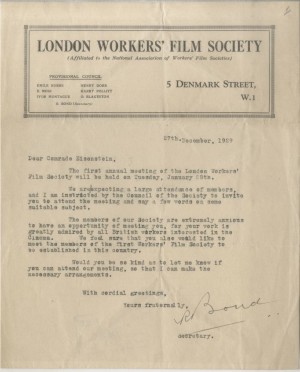

Letter from the London Workers’ Film Society to ‘Comrade Eisenstein’, 27 December 1929 ©Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

“Seryozhenka learned English quickly and became familiar with the literature read by English children,” writes Marie Seton, Eisenstein’s one-time travelling companion, in her 1952 biography. As a child of affluent parents in Riga, Eisenstein wrote poetry in English, conversed in the language with his governess, read Dickens and Edward Lear, graduated to Rudyard Kipling, Lewis Carroll, and Oscar Wilde. The British establishment, and its heroes, fascinated him.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels had become a huge success in Russia, and Eisenstein was a longtime fan. It turns up in the archives: in 1922, while he was still a theatre director in Moscow, he designed costumes for a fantasy amalgam of two fictional sleuths, Holmes and the dime novel private detective Nick Carter. In 1934, two years before Stalin’s Great Terror, the director, a pathological bibliophile, ordered a copy of Vincent Starrett’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, a blend of literary critique and historical analysis, from a British bookshop.

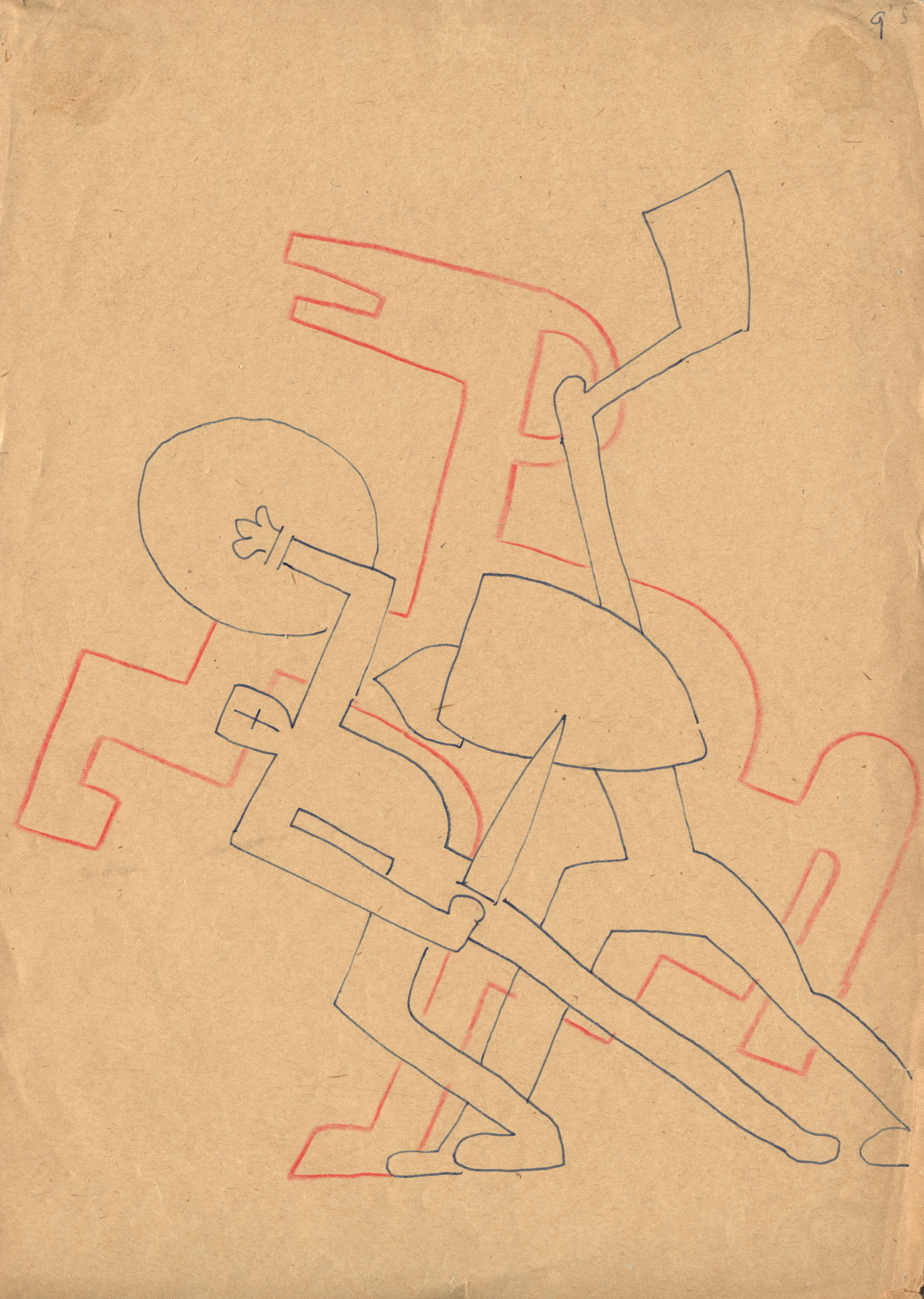

Sergei Eisenstein, preparatory drawing for Ivan the Terrible Part III (unrealised), 1942, pencil on paper ©Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

Eisenstein’s writing extensively references the deductions of detective fiction and dissects it to understand the mechanics of art. “In literature, we also find examples of the physical assembly of a person or an event out of fragments,” he wrote in one essay upon his return to Russia. He describes Holmesian logic as having “Dionysian” intensity, says Holmes’s ability to pick out clues is akin to the ability to “select at a moment’s notice an isolated detail in close-up.”

“Sherlock Holmes for him was the ideal example to how you can bring your intuitive sensual comprehension of the world, together with your rational knowledge,” said Eisenstein biographer Oksana Bulgakowa in a telephone interview. Bulgakowa is currently translating a section of Eisenstein’s writing on detective fiction and said the director was especially interested in “pre-logical thinking,” borrowing the term from French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl. “He tried to explain that novels such as Sherlock Holmes show us the evolution of our system of thinking,” she added. “We first go through the pre-logical, sensual analysis of spatial connections and then we discover the abstract, the cause and effect connections that defined our rational mind.”

Sergei Eisenstein, Thoughts on Music, 1938, pencil on paper ©Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

Because of the scattergun nature of his memoirs and theory, structured like a modernist text and incomplete, we don’t know for sure if Eisenstein turned his magnifying glass to the hoards outside 221B Baker Street during his British sojourn. His frenetic itinerary reflected his passion for the hoary old clichés of British society. He saw an El Greco at the National Gallery, went on an East End pub crawl, grazed the bookshops of the Charing Cross Road, dined at High Table at Trinity College, Cambridge, visited Eton College. “The young gentleman, at the very moment of his birth, is entered for this cold prison ten years in advance,” he writes of Eton College’s pupils in his essay “Museums at Night.” Oddly, the school gets more attention than tourist attractions including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tower of London, or Windsor Castle. Something about the schoolboys carving their names into the desks captured his imagination in the same way Holmes had.

“There’s some fusion of Windsor, Cambridge, Eton, the Tower, that nourishes his imagination when it comes to creating the medieval world of Ivan the Terrible,” said Professor Ian Christie of London’s Birkbeck College, curator of “Unexpected Eisenstein,” a show exploring Eisenstein’s relationship to Britain opening at London’s GRAD Gallery on February 17.

Sergei Eisenstein, preparatory drawing for Ivan the Terrible, 1942, pencil on paper ©Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

Bulgakowa said that Eisenstein’s formal upbringing in an elite Russian family caused him to see Britain as a series of “old stereotypes.” She added: “These were given by Dickens, Chesterton, Conan Doyle, and only later by English modernism.”

Eisenstein left Britain in December 1929, and sailed to New York the following May, unaware of the career-shattering troubles that would soon beleaguer him. His reading material for his Atlantic crossing was Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Rob Sharp is a freelance journalist based in London

沒有留言:

張貼留言