Not New, But Improved - NYTimes.com

opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/01/not-new-but-improved/

November 1, 2009, 9:30 pm — Updated: 5:16 pm

Not New, But Improved

Stella by Pfeiffer Lab

Meet Stella.

At first glance, this little yellow giraffe looks like a lot of other kids’ bath toys. But Stella is made from Renuva, a little-known material that could change for the better the way hundreds of things, from upholstery to airplane wings, are made.

The story of how Stella came to be made from this material, a soy-based alternative to polyurethane (which is typically petroleum-based), provides a model for how stuff can be better designed in the future.

Earlier this year, designer Eric Pfeiffer of Pfeiffer Lab was asked to participate in Humanscale’s Faces in the Wild auction benefiting the World Wildlife Fund. Pfeiffer, who’s had plenty of experience designing kid-friendly products for companies like Paul Frank and Modernseed, had learned about Renuva while researching greener alternatives to fiberglass mannequins. He approached Renuva’s producer, Dow, about a possible collaboration. Working with their chemists, Pfeiffer was able to explore the material intimately, and it has informed other things he’s working on, including furniture and kitchen sponges.

While Stella is one of a kind, designed for W.W.F.’s auction, it also functions as a compelling example for designers and manufacturers of Renuva’s potential uses. In this way, product design becomes a way to highlight a new material and bring it to market.

”We realized we had a great technology in our hands, but it was not clear to us how to communicate this to people who specify materials ending up in finished goods — designers, architects and the like — as well as lay people, the ultimate consumers,” explains Umberto Torresan, Dow’s global marketing manager for polyurethanes. “Eric was ‘the last mile’ to the market we had been missing.”

Says Pfeiffer, “Let’s say the market needs a new bath toy. The typical approach is to look at form, function and the market. But here, we’re leading with the material, and if the material doesn’t do exactly what we need we can go back to the chemists. Essentially, we’re trying to bring material science into the discussion.” This can pave the way toward our using more healthful products, made from renewable and/or recyclable resources, rather than the plethora on the market now that have a negative effect on our health and the environment.

As Cameron Tonkinwise (chair, Business Design and Sustainability, at Parsons The New School for Design) urged, while discussing the future of sustainable design at a recent design education conference, “Enough already. Make it better, don’t make it over.”

So, why soy-based polyurethane? It’s a replacement technology that can “make it better.” While the hazards of petroleum-based polyurethane are greater in the building-block stage as the liquid crude-oil derivatives called isocyanates that are used to make polyurethanes (polyurethane = polyol + isocyanate), polyurethanes can still release toxic V.O.C.’s (volatile organic compounds) into the air. That new car smell, for example? That’s V.O.C.’s released by the interior material.

A switch to a soy-based polyurethane like Renuva reduces dependence on natural gas and crude oil. In fact, according to the United Soybean Board, “For every 1 million pounds of bio-based polyol products purchased, nearly 700,000 pounds of crude oil are saved.” (Polyols are the building blocks used to make the majority of polyurethane products). And as Torresan points out, a commitment to soy-based polyurethane is a commitment to supporting more than 600,000 soybean farmers in the United States.

Renuva is more resistant to ultraviolet rays (it lasts longer outdoors), and it repels water more strongly. Some people have complained that earlier versions had an odor reminiscent of burgers and fries, which is not exactly what you want in a sofa cushion. (For most of us, anyway.)

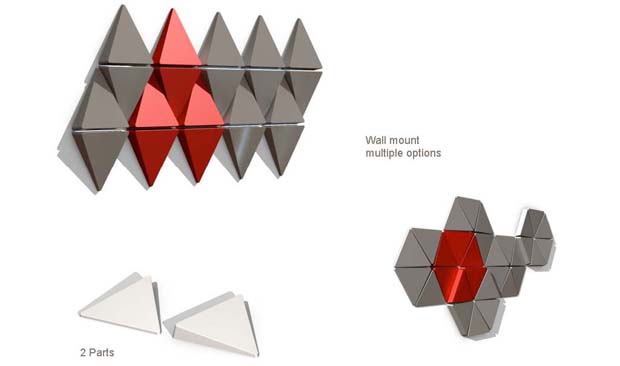

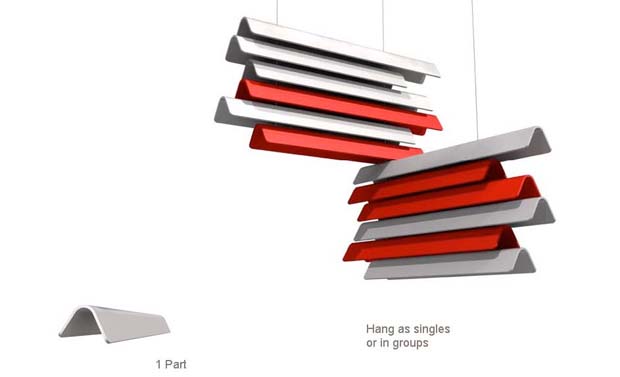

PLYprints ™ by Pfeiffer Lab

Previously, Pfeiffer partnered with Colombia Forest Products, the largest plywood producer in the United States, and the estate of the artist and designer Alexander Girard to create PLYprints™, which was designed to promote Colombia’s PureBond™ formaldehyde-free adhesives. This product went to market, where it functions not only as whimsical wall décor but as an example of the practical applications for greener materials and technologies marketed to consumers, designers and manufacturers. Other collaborations, like the one between New Leaf Paper and Willoughby Innovation Lab, have produced similarly engaging products that push desirability as much as sustainability. This partnership has produced such products as this iconic compositional notebook reinterpreted, its classic marble-ized cover replaced with a leafprint, its content 100 percent post-consumer fiber.

Composition notebook by New Leaf Paper.

With few exceptions — low- or no-V.O.C. paints have literally begun to saturate the paint market, driven by consumer demand for healthful alternatives — we don’t hear enough about more environmentally friendly materials like soy-based polyurethane or formaldehyde-free adhesives. One reason, suggests Pfeiffer, is that “there’s not a lot of innovation because no one is asking for it. This effort [with Stella] is about realigning the supply chain, about having chemical companies talk to consumer brands and asking ‘What do you need?’ rather than saying, ‘Here’s what we’ve got.’” The more obvious reason, of course, is that the petroleum-based version of polyurethane is a $6 billion industry, and most are reticent to mess with what’s working — economically if not environmentally.

Simple Shoes’ BIO-D collection.

Many companies are doing the important job of that “messing” by committing to product design for supply-chain management (that is, improving the fit between supply chain capabilities and product designs). Nike has been a trailblazer with their Considered line, developing shoes and apparel that use less material, incorporate sustainable materials like organic cotton and are easier to recycle, and by developing adhesives made from water instead of toxic chemicals. Notably, they’ve open-sourced much of their research, allowing other companies to make use of their advancements.

Though they hold considerably smaller market share, Simple Shoes is also working to make it better, not over, having just introduced a new collection of biodegradable footwear with outsoles and midsoles designed to break down to dirt in a landfill environment in 20 years. Furniture companies like Steelcase and Herman Miller have also been industry leaders in finding ways to replace current materials with more environmentally friendly ones, and creating products imbued with cradle-to-cradle philosophy. More and more companies are open to sharing their discoveries with others, but it’s been a slow-moving process. It needs to be a faster one.

Sourcing smarter, healthier and more economically viable material solutions presents both a challenge and an opportunity, and signals new imperatives for more meaningful interdisciplinary collaboration. In a recent blog post for the innovation firm Frog Design, Jon Kolko, a creative director of the company, wrote, “The complexity associated with new material introductions and advances has such deep tacit knowledge, and such strong connections to fundamental issues of chemistry, that it can’t continue to be ‘owned’ by designers — it needs to be managed and coordinated by scientists.”

The question of who will ultimately “manage” or “own” the process seems to be less pressing, and politicizing that ownership further only stands to deepen existing disciplinary divides. Recent advances in material sciences and technologies are staggering in their volume — a visit to an innovative materials resource site like Material Connexion is daunting — how to keep up, let alone acquire deep knowledge of all the available options?

So there is an embarrassment of possibilities. The problem is that few of these better alternatives have made it to market, and in fact many continue exist only as compounds in labs or formulas in file cabinets. Often the holdup is simply that companies have not found the right (or most lucrative) ways to put their inventions to use — yet. So involving and informing all parties, from the chemist to the designer to the consumer, can help. “Design is not dead and we need designers,” says Pfeiffer, “but there needs to be a more expanded role for design. We can’t collaborate just with each other, we need to reach out to other communities . . . need to dig into material sciences, sure, but also connect to consumers. I’m thinking about design in a broader context and trying to involve more people.”

We don’t need much in the way of new things. We do need better things. Stella may be just a bath toy, but if she can help bring about this sort of evolution, let’s go ahead and fill up the tub.

*****

TURNING BORING OLD CHEMICAL ENGINEERING INTO DESIGN SEXINESS

DOW CHEMICAL IS RETHINKING ITS PUBLIC FACE AND PARTNERING WITH DESIGNERS WHO MIGHT BE ABLE TO BETTER SELL THEIR INVENTIONS.

Eric Pfeiffer" />

Eric Pfeiffer" />

Eric Pfeiffer, a San Francisco-based industrial designer, probably never imagined himself hand in hand with the chemistry wonks at Dow, the billion-dollar chemicals giant. He's been a designer, pure and simple, almost all his life. At 13, when he couldn't afford a snowboard, he built one by eyeballing magazine pictures.

Nonetheless, at 40, he's found himself front and center in Dow's big push to rework how products are made and place itself hand-in-hand with designers. In turn, Dow expects that this will pave the way for sustainable products made of cutting-edge materials advances, brought to market far sooner.

Chemical companies typically get pulled in only at the end of a daisy chain involving designers and engineers. But with Dow, Pfeiffer is acting as a sort of design ambassador, working between design clients and the company. At the center of this experiment is Renuva, a soy-based material similar to polyurethane plastic. The latter is usually petroleum-based, and it's used in scores of products from cars to furniture to kitchen gadgets.

Renuva, instead, is renewable and organically based. Made from the waste material from soybean processing, it can still be turned into plastics and gels not much different than those derived from petroleum. Which sounds brilliant, but the problem for Dow was getting a mainstream audience to care. Its chemists were more comfortable geeking out over acetates and chlorides—not exactly sexy—than creating a conversation starter for the average consumer.

And that's where Pfieffer's saw an opportunity. He'd help Dow formulate materials that brands (and their consumers) wanted. And he'd realize the materials in a form that consumers could understand. The hope was that new materials would see daylight instead of languishing in some lab.

Umberto Torresan, a marketing manager at Dow, says that this represents a sea-change in how the company views itself. "It took a little bit, to get our mind around this," he says. "But as we started to interact with consumers, we started coming up with more ideas, such as what kinds of products mean something to people. [Pfeiffer] was the bridge for the translation. As a designer, he has a powerful way of communicating things."

Pfieffer has become something of an old-hand at wiggling into musty industries and making himself useful. He recently partnered with plywood heavy Columbia Forest Products and the estate of artist and designer Alexander Girard to produce art prints that showcased Columbia's new formaldehyde-free adhesives.

Renuva is still a tiny part of Dow's overall business. But its collaboration with Pfeiffer could prove influential. Others like DuPont Corian are also engaging with designers and architects early in the design process, though the designer-as-product manager model is still relatively unusual. Pfeiffer sees no reason that designers can't also tap into smaller materials firms. "The days where a designer creates something and just hands it off are numbered," Pfeiffer says.

沒有留言:

張貼留言