Master of gore: the violent, shocking genius of Jusepe de Ribera

From skinned saints to Inquisition torturers, Jusepe de Ribera turned human cruelty into breathtaking works of art. Why isn’t he as celebrated as Caravaggio or Goya?

Wed 19 Sep 2018 06.00 BST

Marsyas as he is flayed by Apollo in Ribera’s 1637 painting Apollo and Marsyas, which appears in Ribera: Art of Violence.

Marsyas as he is flayed by Apollo in Ribera’s 1637 painting Apollo and Marsyas, which appears in Ribera: Art of Violence. Photograph: Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte

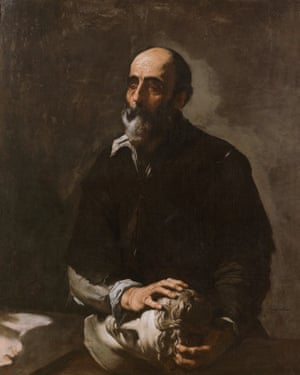

Jusepe de Ribera was a miraculous painter of the male body. Not the heroic, ideal, muscular body of antique sculpture (though he could and did produce that). He was a painter of bloodshot, weeping eyes, of ageing muscles, filthy fingers, snaggle teeth and tousled hair; of leathery arms, double chins, protruding ears, sagging skins and tans that stop abruptly at the neck. He also liked to paint crumpled paper, torn rags, animal pelt and onion skin – all kinds of skin-like things, in fact.

In the darkly glamorous Naples of the 17th century, where he spent most of his life, the Spanish-born painter was the natural successor to Caravaggio. But he is not a household name in Britain. There ’are only a handful of his paintings in British museums. He has never, until now, had a solo exhibition in the UK. Once encountered, his work is unforgettable.

At times, needless to say, he painted women: beautiful, rosy-lipped Madonnas with their adorable, pudgy baby Jesuses. But they pale beside his grottily real men. Occasionally, he painted Saint Mary of Egypt – an elderly penitent and hermit. She is, for me, the only woman who approaches the fascination of his men, with her greying hair, her clavicles protruding from an ageing frame, her still-strong arms and her work-worn, reddish fingers.

Strappado … Inquisition Scene, mid to late 1630s.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Strappado … Inquisition Scene, mid to late 1630s. Photograph: Erik Gould/courtesy Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design

There is also a remarkable work in the Prado, known as The Bearded Woman – a portrait of Magdalena Ventura and her husband. A baby suckles from Ventura’s breast and her face is covered by a long, black beard. When the painting was shown in a landmark Ribera show at New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 1992, the catalogue said “the artist’s genius has transformed an abnormal, almost repugnant medical case into a superb work of art”. Attitudes to gender and the body have, thankfully, changed. Now one might contemplate the dignity and strength Ribera accorded his subject.

Ribera: Art of Violence opens at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London this month, and the title hints at another aspect of his work: his interest in the extremes of physical suffering, often in the service of an especially gruesome martyrdom or mythological scene. This part of Ribera’s work is, for some, troubling. For centuries, he has had a reputation as a violent man – as if to paint or draw his sometimes flinch-inducing scenes of hanging, or flaying, or men bound and tied, he must himself have been cruel. In Don Juan, Byron wrote of Ribera as if his paintbrush were doused in real gore: “Of martyrs awed, as Spagnoletto tainted / His brush with all the blood of the sainted.”

But research undertaken by Ribera specialist Edward Payne, co-curator of the show, clouds this view. Lo Spagnoletto, or the little Spaniard, was Ribera’s nickname. He was born near Valencia in 1591 and moved to Italy aged 16 to study painting, initially settling in Rome before moving to Naples, where he died in 1652. Naples was inescapably violent, as well as populous, cosmopolitan and exciting. Horrific punishments such as the strappado – where a person was suspended by their wrists tied behind their back – were matters of public spectacle.

Skilled skinner … the 1644 painting of Saint Bartholomew being flayed.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Skilled skinner … the 1644 painting of Saint Bartholomew being flayed. Photograph: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

“He would have seen a lot of these punishments being enacted at, for example, the tribunal of the Vicaria in Naples,” says Payne. One of his drawings depicts a man undergoing the strappado while functionaries from the Inquisition – paper and quill in hand – question him. The tortured man’s shoulders are dislocated and he is defecating. Such unblinking scenes of human cruelty make one think of Goya, working more than 100 years later. Ribera was recording the reality of these sombre acts, Payne argues, not revelling in them.

But Payne and his fellow curator Xavier Bray believe there are other reasons for Ribera’s interest in extreme scenes – more academic, classicising, intellectual reasons. His many drawings of male figures bound and tied to trees may seem perverse, but they also represent a kind of working through of an important and famous antique model: the (probably) first-century BC sculpture of Laocoön and his sons in the act of being bound in the coils of deathly snakes. That sculpture, which stood in Ribera’s day as it does now in the Vatican Belvedere, had been discovered buried under a vineyard in Rome the previous century, with Michelangelo himself present at the excavation. Its influence on artists and theorists alike was deep. It is a work that ripples out through the history of art, not least because of its central paradox: an image of suffering and pain transformed into a breathtakingly beautiful work of art....And then, even more fundamentally, there is Ribera’s fascination with two closely related subjects: the mythical musician Marsyas and the saint Bartholomew. These two characters’ stories are horribly similar, both having been flayed alive. The saint was reputedly given this punishment by a furious pagan ruler after he destroyed the heathen idols in the king’s temples; and Marsyas by Apollo, after he lost a musical contest against the god. Although I can’t look at Ribera’s rendering of Apollo and Marsyas, which hangs in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, without wincing, there is more going on than mere gratuitous images of torture.

Ribera returned to these subjects over and over. In a 1624 etching of Bartholomew, the saint’s skin is being stripped from him by a man displaying the true concentration of a skilled craftsman. Twenty years later, the painter returned to the subject for perhaps his most striking version: the saint lies stretched out, staring out at the viewer, his pale skin strongly illuminated, while two workmen go about their dreadful task, again with an air of artisanal commitment. In yet another, the bound Bartholomew awaits his torment as a flayer sharpens his knife. (Owing to the manner of his death, Saint Bartholomew is, perhaps paradoxically, the patron saint of tanners, leatherworkers and doctors.)

In this trio – all included in the exhibition – there is a curious addition: a sculpted head of Apollo, which lies in the foreground of each. In fact, Xavier Bray believes he can even identify the sculptural fragment it is based on: a classical head of the god that Ribera could have seen in a collection in Rome, now owned by the British Museum. The inclusion of this object is an allusion to Bartholomew’s role as an iconoclast, but it could be read as somewhat subversive. The sculpted head is not just of anyone, but of the god of artistic creation. Bartholomew, the saint, was also a destroyer of art.

The Capodimonte painting, meanwhile, does not just include Apollo’s head. The god himself stars as tormentor to Marsyas, who lies prone on the ground, his flushed face creased into a howl of pain. Above, his skin as pale as a statue’s, swoops Apollo in a perfect purple cloak. He seems to be flaying Marsyas with his own hands, scooping brutally at his flesh. In this work, all about the skin and surface of the human body, you can’t help thinking about the skin and surface of the painting itself: there’s such violence here that it brings to mind Lucio Fontana’s works in the 20th century, where the canvas is pierced and cut. Apollo, the great artist-god, is remaking Marsyas’s body in a radical, appalling manner.

Yet another painting features the same sculptural head of Apollo. In Sense of Touch, Ribera’s allegorical painting from 1632, a blind man runs his hands over the cold smooth curls of the antique fragment’s hair. It is an unusual object to use to exemplify the sense of touch. It suggests that sculpture is seeable even by a blind person, whereas a painting, of course, does not have that quality.

Ribera, it seems to me, invokes Apollo whenever he wants to draw our attention to the triumphs and limitations of art, what it can communicate and where it simply fails. He is an artist whose work constantly attempts to escape the expressive constraints of the flat painted surface. When you look at his Apollo and Marsyas, you can almost hear the satyr scream.

• Ribera, Art of Violence, is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 26 September to 27 January.

沒有留言:

張貼留言