'I do not want to die ... until I have faithfully made the most of my talent and cultivated the seed that was placed in me until the last small twig has grown.' – Kathe Kollwitz

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Käthe Kollwitz | |

|---|---|

Käthe Kollwitz self-portrait | |

| Birth name | Käthe Schmidt Kollwitz |

| Born | July 8, 1867 Königsberg, Prussia, now Kaliningrad, Russia |

| Died | April 22, 1945 (aged 77) Moritzburg |

| Nationality | German |

| Movement | Expressionism |

| Influenced by | Max Klinger, Frans Masereel |

| Influenced | Nicolae Tonitza |

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Life and work

[edit] Youth

Kollwitz was born in Königsberg, Province of Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), the fifth child in her family. Her father, Karl Schmidt, was a radical Social democrat who became a mason and house builder. Her mother, Katherina Schmidt, was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a Lutheran pastor who was expelled from the official State Church and founded an independent congregation. Her education was greatly influenced by her grandfather's lessons in religion and socialism.Recognizing her talent, Kollwitz' father arranged for her to begin lessons in drawing and copying plaster casts when she was twelve.[4] At sixteen she began making drawings of working people, the sailors and peasants she saw in her father's offices. Wishing to continue her studies at a time when no colleges or academies were open to young women, Kollwitz enrolled in an art school for women in Berlin. There she studied with Karl Stauffer-Bern, a friend of the artist Max Klinger. The etchings of Klinger, their technique and social concerns, were an inspiration to Kollwitz.[5]

At the age of seventeen, Kollwitz became engaged to Karl Kollwitz, a medical student.[6] In 1888, she went to Munich to study at the Women's Art School, where she realized her strength was not as a painter, but a draftsman. In 1890, she returned to Königsberg, rented her first studio, and continued to draw laborers.[7]

In 1891, Kollwitz married Karl, by this time a doctor, who tended to the poor in Berlin, where the couple moved into the large apartment that would be Kollwitz' home until it was destroyed in World War II.[7] The proximity of her husband's practice proved invaluable:

"The motifs I was able to select from this milieu (the workers' lives) offered me, in a simple and forthright way, what I discovered to be beautiful.... People from the bourgeois sphere were altogether without appeal or interest. All middle-class life seemed pedantic to me. On the other hand, I felt the proletariat had guts. It was not until much later...when I got to know the women who would come to my husband for help, and incidentally also to me, that I was powerfully moved by the fate of the proletariat and everything connected with its way of life.... But what I would like to emphasize once more is that compassion and commiseration were at first of very little importance in attracting me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was simply that I found it beautiful."[8]

[edit] Personal health

It is believed Kollwitz suffered from anxiety during her childhood due to the death of her siblings, including the early death of her younger brother, Benjamin.[9] More recent research suggests that Kollwitz may have suffered from a childhood neurological disorder called Alice in Wonderland syndrome, commonly associated with migraines and sensory hallucinations.[10] However, speculation that this may have directly influenced her work later in life, and in particular inspired the representation of subjects with large heads and hands, rather ignores well-attested formative influences (Max Klinger, Auguste Rodin, etc.) as well as the prevalence of just such distortion for deliberate expressive effect among artistic friends and contemporaries (e.g. George Grosz, Otto Dix).[citation needed][edit] The Weavers

Between the births of her son, Hans in 1892 and Peter in 1896, Kollwitz saw a performance of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers, which dramatized the oppression of the Silesian weavers in Langembielau and their failed revolt in 1842.[7] Inspired, the artist ceased work on a series of etchings she had intended to illustrate Emile Zola's Germinal, and produced a cycle of six works on the weavers theme, three lithographs (Poverty, Death, and Conspiracy) and three etchings with aquatint and sandpaper (March of the Weavers, Riot, and The End). Not a literal illustration of the drama, the works were a free and naturalistic expression of the workers' misery, hope, courage, and, eventually, doom. The cycle was exhibited publicly in 1898 to wide acclaim. But when Adolf Menzel nominated her work for the gold medal of the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm II withheld his approval. Nevertheless, The Weavers became Kollwitz' most widely acclaimed work.[11][edit] Peasant War

Kollwitz' second major cycle of works was the Peasant War, which, subject to many preliminary drawings and discarded ideas in lithography, occupied her from 1902 to 1908. The German Peasants' War was a violent revolution which took place in Southern Germany in the early years of the Reformation, beginning in 1525; peasants who had been treated as slaves took arms against feudal lords and the church. As was The Weavers, this subject, too, might have been suggested by a Hauptmann drama, Florian Geyer. However, the initial source of Kollwitz' interest dated to her youth, when she and her brother Konrad playfully imagined themselves as barricade fighters in a revolution.[12] The artist identified with the character of Black Anna, a woman cited as a protagonist in the uprising.[12] When completed, the Peasant War consisted of pieces in etching, aquatint, and soft ground: Plowing, Raped, Sharpening the Scythe, Arming in the Vault, Outbreak, After the Battle (which, eerily premonitory, features a mother searching through corpses in the night, looking for her son), and The Prisoners. In all, the works were technically more impressive than those of The Weavers, owing to their greater size and dramatic command of light and shadow. They are Kollwitz' highest achievements as an etcher.[12]While working on Peasant War, Kollwitz twice visited Paris, and enrolled in classes at the Académie Julian in order to learn how to sculpt.[13] The etching Outbreak was awarded the Villa Romana prize, which provided for a year's stay, in 1907, in a studio in Florence. Although Kollwitz did no work, she later recalled the impact of early Renaissance art.[14]

[edit] Modernism and World War I

After her return, Kollwitz continued to exhibit her work, but was impressed by the work of younger compatriots—the Expressionists and Bauhaus—and resolved to simplify her means of expression.[15] Subsequent works such as Runover, 1910, and Self-Portrait, 1912, show this new direction. She also continued to work on sculpture.Kollwitz lost her youngest son Peter on the battlefield in World War I in October 1914, prompting a prolonged depression. By the end of the year she had made drawings for a monument to Peter and his fallen comrades; she destroyed the monument in 1919 and began again in 1925.[16] The memorial, titled The Grieving Parents, was finally completed and placed in the Belgian cemetery of Roggevelde in 1932.[17] Later, when Peter's grave was moved to the nearby Vladslo German war cemetery, the statues were also moved.

In 1917, on her fiftieth birthday, the galleries of Paul Cassirer provided a retrospective exhibition of one hundred and fifty drawings by Kollwitz.[18]

Kollwitz was a committed socialist and pacifist, who was eventually attracted to communism; her political and social sympathies found expression in the "memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht" and in her involvement with the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, a part of the Social Democratic Party government in the first few weeks after the war. As the war wound down and a nationalistic appeal was made for old men and children to join the fighting, Kollwitz implored in a published statement:

"There has been enough of dying! Let not another man fall!"[19]While working on the sheet for Karl Liebknecht, she found etching insufficient for expressing monumental ideas. After viewing woodcuts by Ernst Barlach at the Secession exhibitions, she completed the Liebknecht sheet in the new medium and made about thirty woodcuts by 1926.[20]

In 1920 Kollwitz was elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, the first woman to be so honored. Membership entailed a regular income, a large studio, and a full professorship.[20]

In the years that followed, her reaction to the war found a continuous outlet. In 1922–23 she produced the cycle War in woodcut form, including the works The Sacrifice, The Volunteers, The Parents, The Widow I, The Widow II, The Mothers, and The People. In 1924 she finished her three most famous posters: Germany's Children Starving, Bread, and Never Again War.[21]

[edit] Later life and World War II

The interior of the Neue Wache, showing the Käthe Kollwitz sculpture Mother with her Dead Son a World War II war memorial.

Working now in a smaller studio, in the mid-1930s she completed her last major cycle of lithographs, Death, which consisted of eight stones: Woman Welcoming Death, Death with Girl in Lap, Death Reaches for a Group of Children, Death Struggles with a Woman, Death on the Highway, Death as a Friend, Death in the Water, and The Call of Death.

In July 1936, she and her husband were visited by the Gestapo, who threatened her with arrest and deportation to a Nazi concentration camp; they resolved to commit suicide if such a prospect became inevitable.[24] However, Kollwitz was by now a figure of international note, and no further action was taken. On her seventieth birthday, she "received over one hundred and fifty telegrams from leading personalities of the art world", as well as offers to house her in the United States, which she declined for fear of provoking reprisals against her family.[25]

She survived her husband (who died from an illness in 1940) and her grandson Peter, who died in action in World War II two years later.

She evacuated Berlin in 1943. Later that year, her house was bombed and many drawings, prints, and documents were lost. She moved first to Nordhausen, then to Moritzburg, a town near Dresden, where she lived her final months as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony.[25] Kollwitz died just before the end of the war.

Kollwitz made a total of 275 prints, in etching, woodcut and lithography. Virtually the only portraits she made during her life were images of herself, of which there are at least fifty. These self-portraits constitute a life-long honest self-appraisal; "they are psychological milestones".[26]

[edit] Legacy

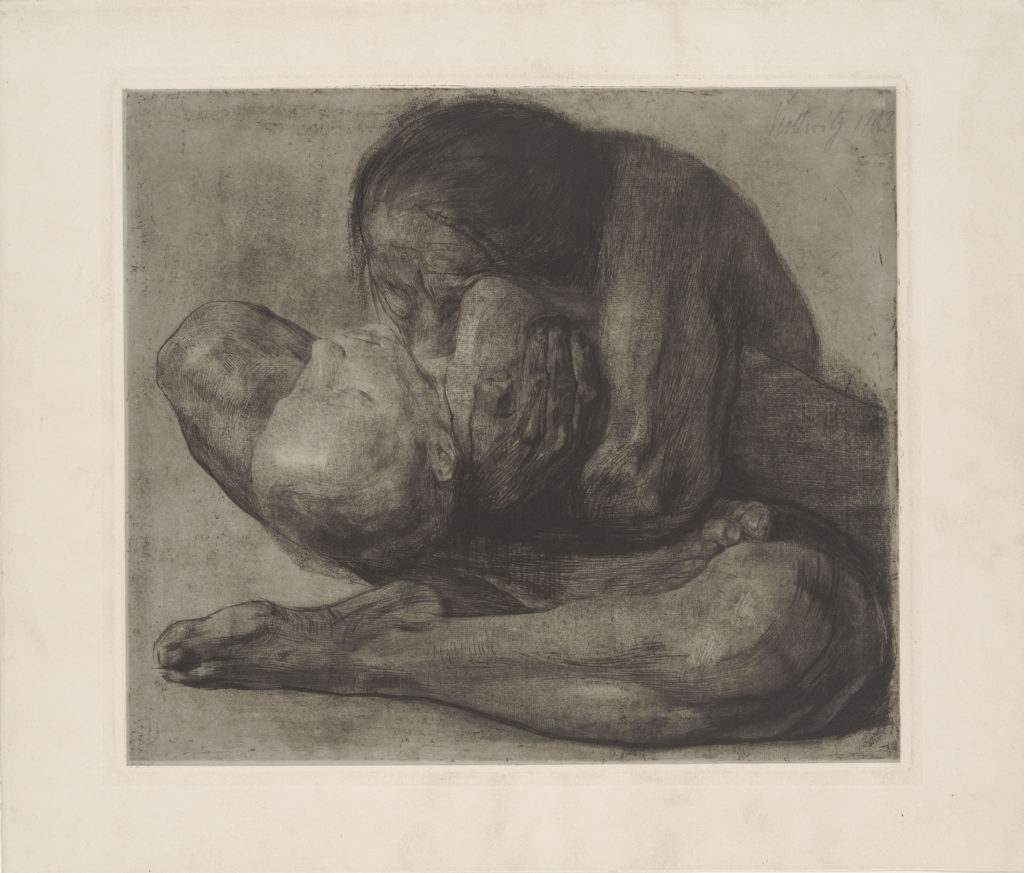

Her silent lines penetrate the marrow like a cry of pain; such a cry was never heard among the Greeks and Romans.[27]Käthe Kollwitz is a subject within William T. Vollmann's Europe Central, a 2005 National Book Award winner for fiction. In the book, Vollmann describes the lives of those touched by the fighting and events surrounding World War II in Germany and the Soviet Union. Her chapter is entitled "Woman with Dead Child", after her sculpture of the same name.

An enlarged version of a similar Kollwitz sculpture, Mother with her Dead Son, was placed in 1993 at the center of Neue Wache in Berlin, which serves as a monument to "the Victims of War and Tyranny".

Artist Birgit Stauch depicted Kollwitz in a bronze bust displayed in the Käthe-Kollwitz-Schule in Esslingen, one of more than 40 German schools named after her.[28][29][30][31][32][33]

Two museums, one in Berlin[34]and Cologne,[35] are dedicated solely to her work.

[edit] References

- ^ Bittner, Herbert, Kaethe Kollwitz; Drawings, page 1. Thomas Yoseloff, 1959.

- ^ Fritsch, Martin (ed.), Homage to Käthe Kollwitz. Leipzig: E. A. Seeman, 2005.

- ^ "The aim of realism to capture the particular and accidental with minute exactness was abandoned for a more abstract and universal conception and a more summary execution". Zigrosser, Carl: Prints and Drawings of Käthe Kollwitz, page XIII. Dover, 1969.

- ^ Bittner, page 2.

- ^ Kurth, Willy: Kaethe Kollwitz, Geleitwort zum Katalog der Ausstellung in der Deutschen Akademie der Kuenste, 1951.

- ^ Bittner, page 3.

- ^ a b c Bittner, page 4.

- ^ Fecht, Tom: Käthe Kollwitz: Works in Color, page 6. Random House, Inc., 1988.

- ^ Bittner, pages 1-2.

- ^ Drysdale, Graeme R. (May 2009). "Kaethe Kollwitz (1867–1945): the artist who may have suffered from Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". Journal of Medical Biography 17 (2): 106–10. doi:10.1258/jmb.2008.008042. PMID 19401515. http://jmb.rsmjournals.com/cgi/content/abstract/rsmjmb;17/2/106?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=1&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=50&resourcetype=HWCIT.

- ^ Bittner, pages 4-5.

- ^ a b c Bittner, page 6.

- ^ Bittner, pages 6-7. During this time she also visited Rodin twice.

- ^ "But there, for the first time, I began to understand Florentine art." Kollwitz, Kaethe: The Diaries and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, page 45. Henry Regnery Company, 1955.

- ^ "Nevertheless I am no longer satisfied. There are too many good things that seem fresher than mine... I should like to do the new etchings so that all the essentials are strongly stressed and the inessentials almost omitted." Kollwitz, page 52.

- ^ Bittner, page 9.

- ^ "I stood before the woman, looked at her—my own face—and wept and stroked her cheeks." Kollwitz, page 122.

- ^ "The elements of her nature and her art can often be felt more immediately in the drawings than in the prints, even much that in the latter has scarcely found a fulfillment." Kurth, Willy: Kunstchronik, N.F., Vol. XXXVII, 1917.

- ^ Kollwitz, page 89.

- ^ a b Bittner, page 10.

- ^ Bittner, page 11.

- ^ Dorothea Körner, "Man schweigt in sich hinein – Käthe Kollwitz und die Preußische Akademie der Künste 1933-1945" Berlinische Monatsschrift (2000) Issue 9, pp. 157–166. Retrieved July 8, 2010 (German)

- ^ Jane Kelly, "The Point is to Change it" jstor.org/stable/1360622 (fee required) Retrieved July 9, 2010

- ^ Bittner, page 13.

- ^ a b Bittner, page 15.

- ^ Zigrosser, page XXII, 1969.

- ^ Gerhart Hauptmann, quoted by Zigrosser, page XIII, 1969.

- ^ Short explanation of the school's name, with links to three articles about Kollwitz Käthe-Kollwitz-Schule Esslingen, official website. Retrieved July 9, 2010 (German)

- ^ List of hits for Käthe-Kollwitz-Gymnasium Google website. Retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ List of hits for Käthe-Kollwitz-Schule Google website. There is some overlap because some schools use both "Schule" and another term to refer to themselves. Retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ List of hits for Käthe-Kollwitz-Realschule Google website. Retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ List of hits for Käthe-Kollwitz-Hauptschule Google website. Retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ List of hits for Käthe-Kollwitz-Gesamtschule Google website. Retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ Käthe Kollwitz Museum Berlin Official website. Retrieved January 30, 2011

- ^ Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln Official website. Retrieved January 30, 2011 (German)

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Käthe Kollwitz |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Käthe Kollwitz |

维基百科,自由的百科全书

柯勒惠支出生於俄羅斯克尼哥斯堡(現在的加里寧格勒)的一個德裔家庭,原名凱綏·施密特。14歲時即開始學習繪畫,1884年進入柏林女子藝術學院學習,後來又到慕尼黑學習。1889年和在貧民區服務的醫生卡爾·柯勒惠支結婚,1898年開始在柏林女子藝術學院任教。其間幾次遊歷巴黎和義大利。1909年回 國後為一個漫畫雜誌Simplicissimus.工作。這時她已經成為一個社會主義者。她的早期作品《織工反抗》、《起義》和《死神與婦女》、《李卜克 內西》 、《戰爭》(組畫)等,不僅以尖銳的形式把在資本主義制度下工人階級的悲慘命運和勇於鬥爭的精神傳達出來,而且喚醒人們反對侵略戰爭,要根除戰爭根源,實 現世界大同的理想。

1914年在第一次世界大戰中,他的兒子被征入伍在西線陣亡。1920年她和愛因斯坦等人組織成立了國際援助工人組織。1932年她和其他社會主義者組成反對納粹的陣線,希特勒上台後,她被取消普魯士學院院士的榮譽,雖然她是第一位被選為普魯士學院的女性院士,並禁止她的作品參加展覽。1940年她丈夫去世,1945年他的孫子又在東線陣亡。1943年她的住宅被炸毀,她離開柏林到德勒斯登附近的一個小鎮居住,並在那裡逝世。

她因為和丈夫居住在貧民區,了解普通人民的貧困境遇,她的作品從一開始就反映普通人民的貧苦生活,因此在第一次獲得金獎時,就被當時的威廉二世國王取消。後來她又創作了《悼念卡爾·李卜克內西》和為工人組織創作的一系列招貼。兒子去世後又創作了許多悲傷母親的形象,宣傳反戰思想。她的作品充滿悲傷和凄慘的情緒,如實反映了19世紀末20世紀初德國底層人民的可悲狀況。柯勒惠支還對銅版畫和石版畫的技術有許多改進和創造。

柯勒惠支的作品首次被魯迅*先生介紹到中國,對中國現代版畫的發展起了很大的影響。魯迅評價她的作品是:「她以深廣的慈母之愛,為一切被侮辱和損害者悲哀,抗議,憤怒,鬥爭;所取的題材大抵是困苦,飢餓,流離,疾病,死亡,然而也有呼聲,掙扎,聯合和奮起。」

*凱綏·柯勒惠支版畫選集 序目1936/2/17 (原名Kaethe Schmidt 夫姓Kollwitz )

1945年4月22日卒於德勒斯登。

生平大事記

- 1867年(與諾爾德同年)生於東普魯士的柯尼斯堡。

- 1884年在柏林美術學院學習,後又在慕尼黑繼續深造。

- 1885-1886年在柏林從師施陶費爾-貝爾恩,學習馬克斯·克林格爾的蝕刻組畫。

- 1890年創作了第一批銅版畫。1891年與「施診醫生」卡爾·珂勒惠支結婚。

- 後經畫家門采爾推薦,當選普魯士美術學院成員,主持版畫部工作。

- 1919年從師巴拉赫,改學木版畫。

- 最初的作品是《紀念李卜克內西》,此後在1922-23年創作了組畫《戰爭》。

- 1927年應邀訪問蘇聯,蘇聯的社會主義建設大大鼓舞了她 ,回國後創作的石版畫《遊行示威》、《團結就是力量》、《母與子》等,表明了她對無產階級解放事業的新認識,藝術水平也達到一個新的境地。

- 1931年她的作品被魯迅介紹到中國來,1936年又出版她的作品集,對中國新木刻運動的發展起了推動作用。

- 作為一個勇敢的反納粹女戰士,1933年她憤然離開了普魯士美術學院。

- 1933年希特勒上台,她雖然受到迫害,仍堅持作畫,代表作《死亡》和《哀悼基督》以粗獷的線條,強烈的黑白對比,描繪了生與死的激烈搏鬥,宣洩了她憤懣的情緒。

- 1942年「全面開戰「時,她發表了最後一幅木版畫作品《不要把收穫的糧食磨成粉》。

- 1945年戰爭即將結束時死於德勒斯登附近莫里茨山

- 1979年北京舉辦《珂勒惠支作品展》,展出了她一生中最主要的作品113件。

柯勒惠支的主要作品

- 窮困(1893年)

- 末日(1897年)

- 下工的工人(1897年)

- 自畫像(1897年)

- 起來(1899年)

- 自畫像(1900年)

- 哀悼去世孩子的婦女1903年)

- 覺醒(1903年)

- 戰場(1907年)

- 囚徒(1908年)

- 志願者(1920年)

- 母親們(1921年)

- 不要再發生戰爭(1924年)

- 自畫像(1924年)

- 死神的召喚(1934年)

- 自畫像(1938年)

外部連結

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/missing-artworks-kathe-kollwitz-1119983

Found by Finnish Customs Agents, Three Missing Works by Käthe Kollwitz Surface in the Nick of Time

Considered lost since the end of World War II, three works by the German artist have been identified and are en route to a museum in Dresden.

Three recently identified artworks by the German artist Käthe Kollwitz, missing since the end of World War II, are being returned to the Kupferstich-Kabinett, the prints collection in Dresden. The timing is serendipitous, as an exhibition including 70 works by the artist opens there today.

Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, the museum’s head conservator, told artnet News in an email that the works have yet to arrive at the museum. In fact, they are being brought by a colleague and will arrive November 8 at which time more information will be made available. The works were retrieved by the Finnish customs in Helsinki back in 1984, but it was only a month ago that the museum was notified that the works were indeed by Kollwitz, and were confirmed as having belonged to the museum before going missing by the end of World War II.

They were finally identified by the Kupferstich-Kabinett’s mark on the back of the works and old inventory numbers, but at this time not much more is known about them.

Käthe Kollwitz, Die Mütter (Blatt 6 der Folge “Krieg”), 1921-1922.

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © SKD

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © SKD

The Dresden show is one of several exhibitions across Germany to mark the artist’s 150th anniversary: Here, her drawings and prints will be presented in a double exhibition alongside the South African painter Marlene Dumas.

The museum houses one of the most prominent collections of Kollwitz’s work, whose figurative images and sculptures are best-known for their politically charged depictions of then-marginalized. The Kupferstich-Kabinett Dresden was the first public museum to promote her work, under the directorship of Max Lehrs (1855-1938), before World War II broke out.

It was during an era in which it was nearly impossible for female artists to gain recognition or respect in the art world, and were largely invisible from intellectual, political, and artistic discourse. Kollwitz herself was denied access to the academies, and even denied a prize on the basis that it was rather for “deserved men.” Despite this, she rose.

Käthe Kollwitz (1967-1945) Woman with Dead Child, 1903.

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © SKD

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © SKD

Kollwitz, who died in 1945, has posthumously become a predominant figure in the German art scene, with streets and plazas named after her—especially in Berlin, where she spent many years living and working.

“As the works haven’t arrived yet we will need to think about this question a bit later,” says Kuhlmann-Hodick in regards to whether these retrieved works will be included in the exhibition. “Perhaps they will be displayed in our public prints and drawings study-room adjacent to the exhibition room.”

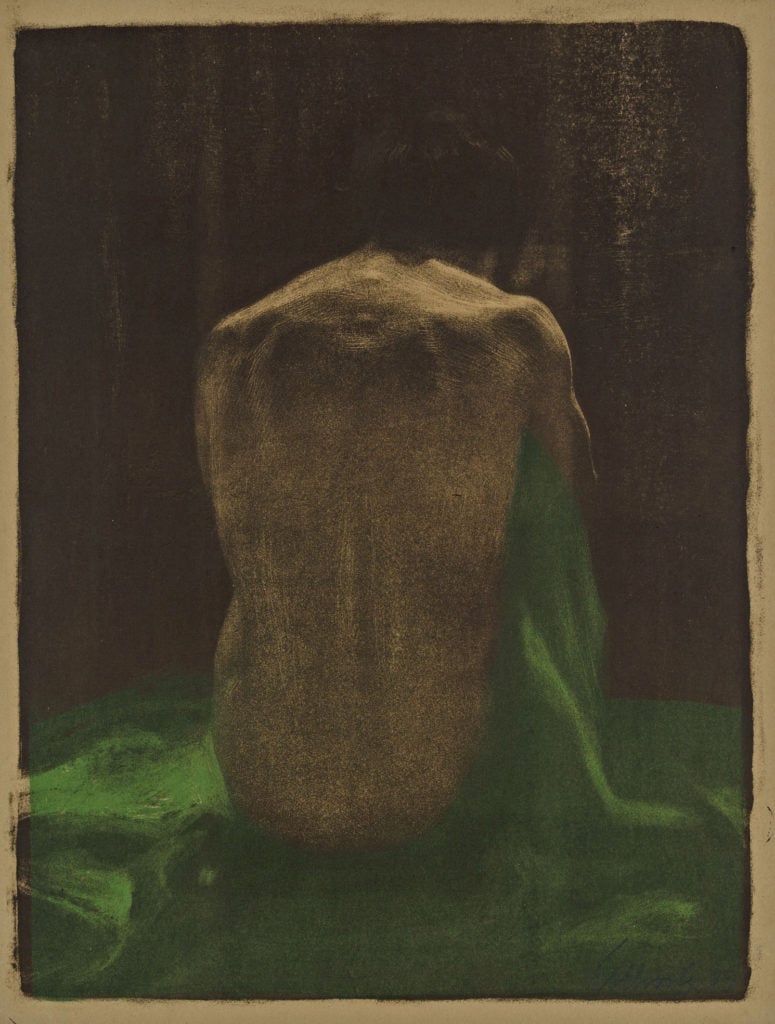

Käthe Kollwitz Weiblicher Rückenakt auf grünem Tuch, 1903.

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © State Collection Dresden

Kupferstich-Kabinett, © State Collection Dresden

“Käthe Kollwitz in Dresden” is on view at the Kupferstich-Kabinett Dresden from October 19 – January 14, 2018.

沒有留言:

張貼留言